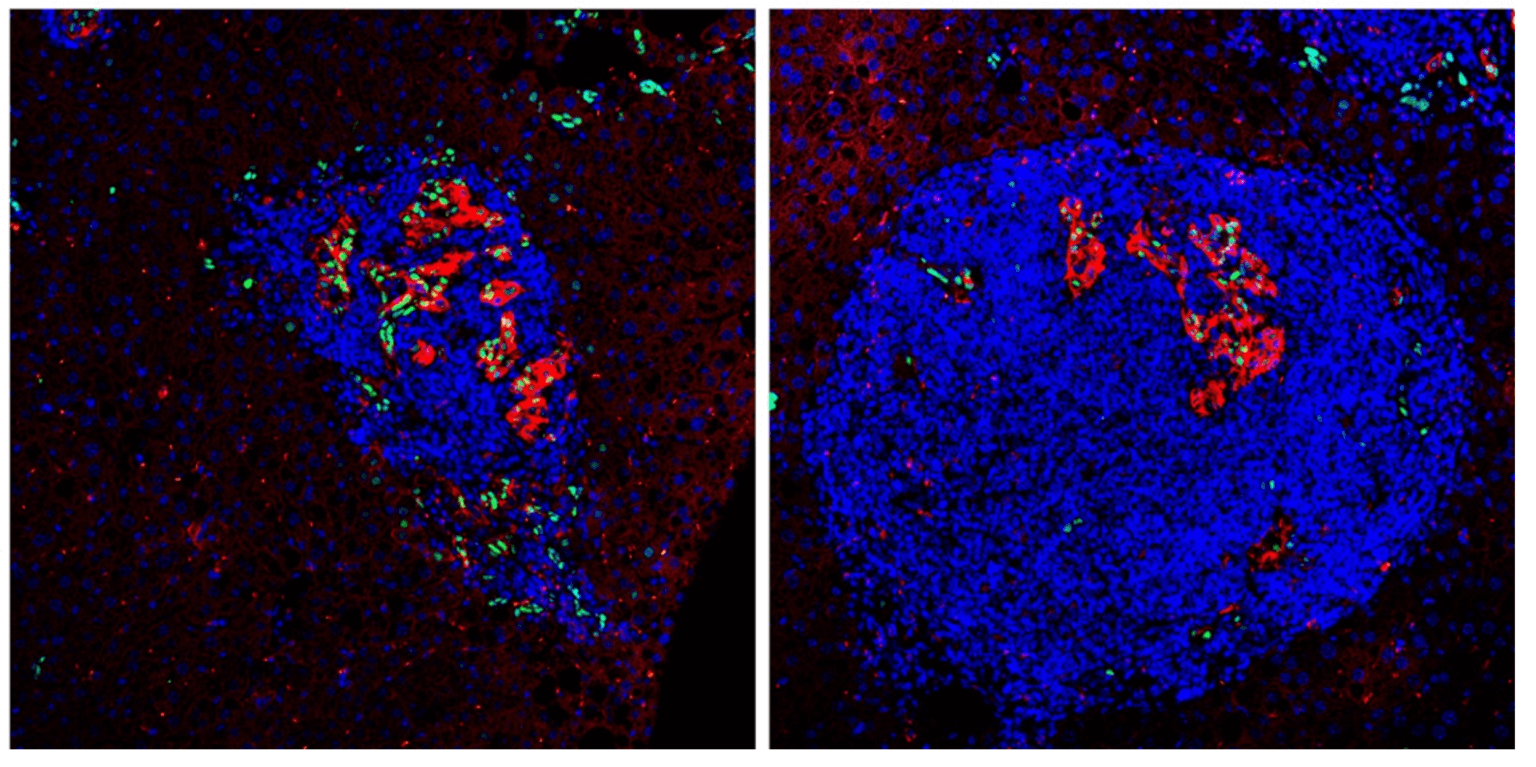

Pools of immune system cells taken from patients and mice with liver cancer and melanoma, partly composed of tired immune cells

One of the functions of immune system cells is to kill cancer cells. But sometimes, the cancer cells develop mechanisms that allow them to disrupt the immune activity against them. In such a situation, the body fails to control the rate of their division - they multiply without control, spread and may cause serious damage to tissues and organs.

Primary liver cancer (which first developed from the liver cells, and did not reach them from another area of the body), is one of the deadliest types of cancer. Every year about 700 people die from it in the world, and in recent decades its incidence has tripled. Less than a third of patients diagnosed with this cancer remain alive for six months, and only about five percent survive for five years or more.What is the question? Why do some immune system cells help cancer spread? And is there a way to turn the pests into useful ones?

Prof. Eli Pikarski from the Department of Immunology and Cancer Research at the Faculty of Medicine at the Hebrew University and his team are investigating the connection between inflammation of the liver and liver cancer. "Any disease that causes liver inflammation," he says, "increases the risk of liver cancer. Almost all patients with this cancer have a liver disease in the background that causes inflammation. And if we understand how inflammation leads to cancer - by what mechanisms - maybe we can prevent it."

In a study that began ten years ago, Prof. Pikarski and his team discovered a connection between the development of liver cancer and tertiary lymphatic follicles - aggregates that include many types of immune system cells. For example, B-type lymphocytes, which produce antibodies and are essential for fighting pathogens (disease-causing bacteria and viruses), and T-type lymphocytes, which can eliminate body cells infected with pathogens or cells that have undergone a cancerous transformation. These accumulations develop in adult life in response to various diseases and constitute a kind of forward positions of the immune system; When an enemy such as a bacterium or virus invades the body or when cancerous changes develop in it - the body produces these aggregates in the area where the immune response is required. However, sometimes they fail and are even promoted in their position.

Prof. Pikarski: "These cells are extremely essential for preventing cancer, but they don't always work as they should, and we are trying to understand why." In their research, Prof. Pikarski and his team discovered that aggregates may also form in the liver that cause cancer cells to proliferate instead of killing them. This is because immune cells in them, lymphocytes of different types, secrete a cytokine (a protein that promotes inflammation) of the LT type. They showed that if this cytokine is inhibited, the cancer cells do not spread. "Clumps in the liver often secrete this cytokine for effective activation of the immune system and protection against cancer, but sometimes cancer cells take advantage of it for the purposes of spreading," says Prof. Pikarski. The researchers discovered a connection between the development of liver cancer and tertiary lymphatic follicles - clumps that include many types of The cells of the immune system, for example, B lymphocytes, which produce antibodies and are essential for fighting pathogens

The researchers asked themselves why some aggregates help the spread of cancer and some prevent it, and whether there is a way to turn harmful aggregates into useful ones. They hypothesized that the pro-cancer effect of LT occurs only if the aggregates for some reason lose their basic ability to kill cancer cells, and asked to test this. Therefore, in their latest study, which was done in collaboration with Prof. Michal Lotem, director of the Center for Melanoma and Cancer Immunotherapy at the Hadassah Medical Center, they used molecular methods to examine aggregated cells from samples taken from liver cancer and melanoma patients and from mice with liver cancer.

They discovered that in the harmful clusters there are "tired" T lymphocytes - those that do not work. For example, when they are exposed to cancer cells - they do not thrive and do not secrete substances that can kill the cancer cells. The researchers wanted to discover the cell in the clusters that might induce the fatigue, so they eliminated (by genetic engineering) various immune cells. When ILCs (innate lymphoid cells) were eliminated, T lymphocytes began to thrive and became helpful (triggered an immune response and prevented the spread of cancer cells). The ILCs are cells that were only recently identified, and now their ability to suppress the activity of T cells has been discovered for the first time. It may be a regulatory mechanism of the immune system, whose role is to protect against its excess activity that can cause autoimmune diseases.

Today, the researchers - with the help of a research grant from the National Science Foundation - are trying to understand what is the mechanism that causes T lymphocytes to tire - that is, what signal is secreted from ILCs that causes this. They hope that a treatment directed against this signal will be able to activate the immune system and prevent the development of liver cancer and possibly other types of cancer.

Life itself:

Prof. Eli Pikarski, 54 years old, lives in Jerusalem. A great lover of science ("it's also a hobby and not just an occupation") and loves to read books.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- A new family of self-organizing materials

- Weizmann Institute scientists have discovered a new "strategic partner" for the development of cancer

- Friend brings a friend

- Changing meal times may reduce the accumulation of fats in the liver

- For the first time, researchers created a functioning human liver from induced stem cells * In the future, the need to wait for a liver transplant will disappear