The institute's scientists succeeded in turning migrating cells into stationary cells. The hope: finding a way to stop cancer metastases

The formation of metastases - the process in which cancer cells leave the original tumor site where they were formed, and go on a wandering journey, at the end of which they settle in new organs - is the main cause of death of cancer patients. Preventing this phenomenon may save many lives. Therefore, many scientists, in different parts of the world, are trying to understand what causes one cancerous tumor to grow in its place, and another tumor to "launch" cells that go out to establish metastases?

Prof. Benjamin Giger, Dean of the Faculty of Biology at the Weizmann Institute of Science, and research student Suha Nefer Abu-Amara, decided to look for the genes responsible for the migration ability of cancer cells. To this end, Soha Nefer Abu-Amara developed a method for simultaneously testing the mobility capacity of many cells. The technique is based on covering an area with granules

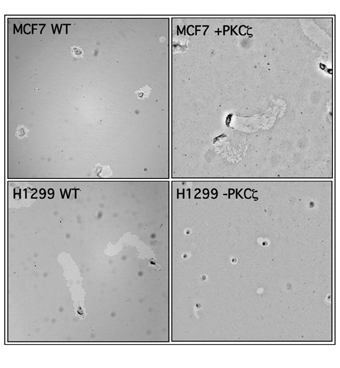

Tiny - much smaller than the cells themselves. When the cells move within this "carpet", they move the grains aside, and leave marks along the path of movement, similar to beetles that leave tracks in the sand. At this stage, the scientists conducted a kind of running competition for the cells. They took a large amount of cells with poor migratory capacity originating from non-metastatic breast cancer, and activated in them, at the same time, overexpression of a wide variety of genes that are associated with cancer that can produce metastases. Some of the cells that underwent changes in their gene expression became highly migratory, which caused them to leave long traces in the granule carpet. These cells, which contained the genes that cause migration, were used by scientists as laboratories to isolate these genes and identify them.

Innovations in digital microscopy allowed Prof. Giger and Soha Nafer Abu-Amara to obtain important information from tracking the cells. The tests of cell movements over time and the shapes of the migration paths clarified various details about the mechanisms of cell movement. With the help of a multidisciplinary research team, in which research student Tal Shai from the Department of Physics of Complex Systems, Dr. Merv Galon from the Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, and Prof. Tzvi Kam from the Department of Molecular Cell Biology, all from the Weizmann Institute of Science, together with Steven Iskov from the University of Harvard, they identified five genes whose overexpression caused the cancer cells to move.

Does increased mobility mean an increase in the degree of aggressiveness or invasiveness of the cancer? To answer this question, the scientists inserted the migration-promoting genes they discovered into cells that were characterized by non-migration. The result: cells in which these genes were expressed to a normal extent formed a local cancer tumor, which did not "send" metastases; Whereas cells in which these genes were overexpressed began the processes of establishing a metastasis of an aggressive nature.

Later, the researchers used new approaches to stop the expression of one of the genes they identified in the cancer cells that are particularly prone to migration and establishing metastases. In this way they managed to turn a mobile cell into a stationary cell. "This finding," says Prof. Giger, "surprises and excites us especially. Furthermore, this gene encodes an enzyme whose activity can, in principle, be inhibited using various substances. Such inhibitory substances may, in the future, form a basis for the development of a drug that will prevent the formation of cancer metastases."

2 תגובות

Well done. It sounds very promising.

Apparently, if there are no adverse reactions to the migration inhibiting substances that will be developed in the future, it would be worthwhile to give them to the entire population as a vaccine. This way people knew that even if they had cancer, it would only be localized and would not be able to spread and destroy the body.

And such a drug will help provided that the cancer was discovered before it metastasized!?