Until now, silencing a chromosome containing thousands of genes was considered impossible because it was necessary to silence each gene individually. The scientists used a means by which the body silences one X chromosome in female mammals to silence the unnecessary chromosome 21 in Down syndrome patients

Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have for the first time been able to substantiate the claim that a gene that enables the "turning off" of an entire chromosome, which is naturally found in the body of the X chromosome, can neutralize the redundant chromosome responsible for trisomy 21, also known popularly as Down syndrome, a genetic disorder characterized by in the disruption of cognitive ability.

The discovery provides the first evidence that the genetic defect responsible for Down syndrome can be suppressed in human cells - although for now it is a culture and not cells inside the body. The experiment paves the way for the investigation of the pathology of the cell and the identification of the trans-genome pathways that affect patients with this syndrome, a goal that has so far proven to be elusive.

Achieving this goal will improve scientists' understanding of the basic biology behind Down syndrome and may one day help find targets for future drugs. Details of the study were published on the website of the journal Nature.

"In the last decade, we have seen progress in the efforts to correct disorders resulting from a disruption in a single gene, when we started with cell cultures and in some cases we also progressed to experiments inside the body and even clinical experiments" says the lead researcher Prof. Jean Lawrence - an expert in cell biology and developmental biology.

"In contrast, genetic correction of hundreds of genes along a redundant chromosome was not possible. Our hope is that for people living with Down syndrome, this opens up many fascinating avenues for researching the syndrome now and curing their disease and achieving 'chromosome healing' in the future.

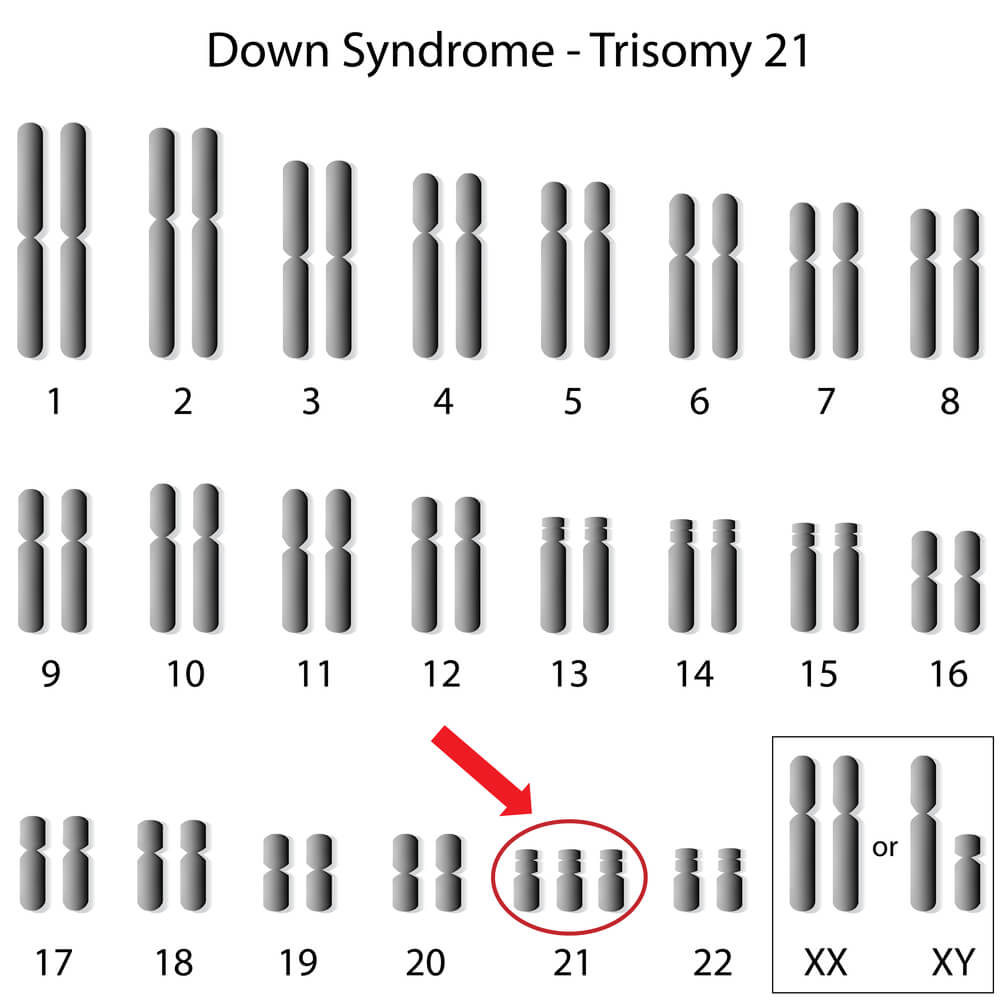

Humans are born with 23 pairs of chromosomes including two sex chromosomes, and in total the number of chromosomes in each body cell reaches 46. Those with Down syndrome are born with three copies of chromosome 21 (instead of two), and the syndrome of three chromosomes 21 causes cognitive limitations, the development of Alzheimer's at a young age, a high risk of childhood breast cancer, heart defects and disruptions in the functioning of the immune system and hormones.

Unlike genetic diseases caused by a single gene, gene correction of an entire chromosome in cells containing three copies of it was not possible, even in cell cultures.

The scientists took advantage of the ability of an RNA-encoded gene known as XIST that is normally responsible for turning off one of the two X chromosomes found in the body of female mammals. They proved that the unnecessary chromosome 21 can also be silenced with the help of the same gene by using the patient's own stem cells.

The natural role of the XIST gene, located on the X chromosome, is to effectively silence one of the two X chromosomes in the female's body cells and thus ensures that the expression of the genes on the woman's X chromosome will be similar to that of the man, who has only one X chromosome.

The XIST RNA is produced early in development from one of the woman's two X chromosomes. This unique RNA "paints" the X chromosome and adjusts its structure so that its DNA will not be expressed or produce proteins and other components. The process deactivates most of the genes of the extra chromosome.

Lawrence and her colleague Dr. Lisa Hall conceived the idea that this effect could possibly be imitated by the redundant chromosome 21 in triple gene cells. Dr. John Jiang, also from the Department of Developmental Biology and Cell Biology, together with Lawrence began a research project in an attempt to insert the XIST gene into one of the 21st chromosomes. They first did this with induced stem cells derived from fibroblast cells donated by Down syndrome patients. These stem cells have the ability to create different types of cells in the body. They showed that the large XIST gene can be inserted at a certain point in the chromosome using zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology, an important tool obtained in collaboration with Sangamo Biosciences from California. Subsequently the XIST shield RNA repressed genes along the redundant chromosome, leaving gene expression levels close to normal and effectively silencing the chromosome.

These findings open new avenues for medical scientists in the field of gene expression to study Down syndrome in a way that was not possible before.

Determining the cellular pathology and the genetic pathways responsible for the syndrome have encountered difficulties due to the complexity of the syndromes and the genetic and epigenetic variation between humans and cells. For example, previous studies hypothesized that cell culture in Down syndrome patients may be defective, but the differences between humans and cell lines made it difficult to prove the hypothesis with certainty. By controlling the expression of the XIST gene, Lawrence and her colleagues were able to compare cultures of cells taken from Down syndrome patients that were otherwise completely identical with or without silencing the redundant chromosome. They showed that Down syndrome cells were defective, among other things, in both cell division and differentiation, and both processes were corrected by silencing one of the 21 chromosomes by XIST.

"This turns the spotlight on the potential of these experimental models for researching different questions in different cell types, and in mice used as a model for Down's syndrome," says Lawrence. "We now have a powerful tool for identifying and researching the cellular pathologies and pathways directly caused by the overexpression of chromosome 21."

2 תגובות

Yibote... I guess... the spelling mistakes on the site are really annoying and take away from the sense of scientific credibility. Can't use a word processor with spell check?