An explanation for the resistance that some cancer cells develop to chemotherapy may indicate a research direction that may lead to finding a way to weaken the resistance, so that the drugs will be effective again

The strong, as we know, survive. But what do you do when the powerful is harmful to the entire system? Weizmann Institute of Science scientists recently faced this question in the smallest and most deadly dimensions - in cancer cells. In an article published in the scientific journal Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Prof. Menachem Rubinstein, from the Department of Molecular Genetics, offered an explanation for the resistance that some cancer cells develop to chemotherapy. This explanation may indicate a research direction that may lead to finding a way to weaken the resistance, so that the drugs will be effective again.

Chemotherapy is one of the common ways to fight cancer. But even if the treatment is successful, and the tumor is in retreat, there is always the chance that it will erupt again. In many cases, the renewed outbreak is stronger and more resistant to the existing treatments, and in such a situation it is difficult to find a solution. The pharmaceutical industry has been dealing with this problem for four decades, and one of the prevailing assumptions is that the resistance is created by proteins that are in the cell wall, and "suck" out the medicinal substances. But even blocking the pumps did not solve the problem.

Scientists in the research group headed by Prof. Rubinstein decided to take one step back - and re-examine the process. "We realized that if blocking the pumps does not solve the problem of the resistance of the cancer cells, there must be another mechanism," says Prof. Rubinstein. Over the years Prof. Rubinstein and his group have been investigating the role of the protein called CEBP beta. This protein appears in cells in one of two forms - LIP and LAP. LAP is the complete protein, which serves as a regulator of the activity of many genes in the cell, while LIP is a shortened form of the same protein, which may take the place of LAP, thus inhibiting its action. Many studies previously showed that LAP and LIP appear together in many main types of cancer cells, but their role was not clear. Prof. Rubinstein and his group previously showed that LAP prevents the death of cancer cells exposed to stress, such as chemotherapy, while LIP increased the death of these cells by inhibiting the action of LAP.

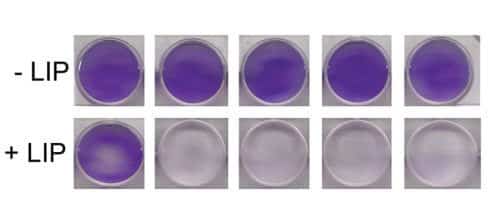

In a study recently carried out in Prof. Rubinstein's laboratory, which was led by guest scientist Prof. Chiara Riganti from the University of Turin, in collaboration with Sarah Barak, the scientists found, to their surprise, that many types of cancer cells, which are resistant to a wide range of chemotherapies, completely lack the LIP protein. Furthermore, when they injected into these cells the gene responsible for creating LIP, the cells responded well to all those chemotherapy treatments. However, the processes that exist today for introducing genes into cells are not efficient enough, so some cells will always manage to evade the treatment and continue to thrive.

Later in the study, Prof. Rubinstein examined another question: Why is there actually no LIP in the chemotherapy-resistant cells? The answer, it turns out, is that LIP does indeed form in them, but it breaks down immediately. But as soon as the scientists managed to understand the source of the problem, the solution suddenly seemed simple: there are existing drugs, approved for use, which, among other things, are also able to delay the breakdown of LIP. Will it be possible to delay the spread of cancer using these drugs? Experiments in cell cultures in the laboratory yielded positive results. The scientists say that more studies are now needed, in the hope that they will lead to the use of combinations of these drugs with chemotherapy. Such combinations may provide an answer in those cases where the tumor is resistant to conventional treatments.

Tags: