How did the Ashkenazim take over the world?

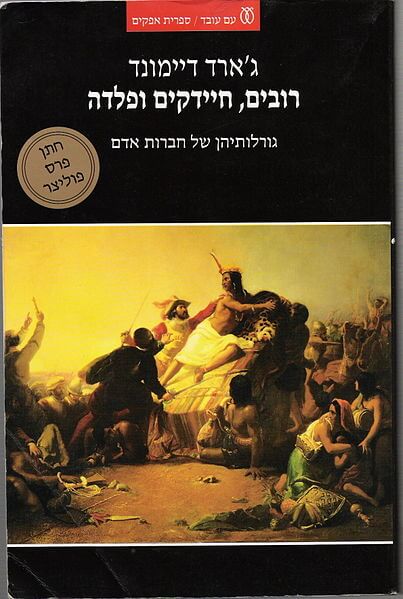

Review of the book Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond. Translated from English: Atalia Zilber. Ofakim series, published by Em Oved, 376 pages, NIS 89

Tal Golan

On the morning of November 16, 1532, the city of Cajamarca in the highlands of Peru was the scene of one of the most dramatic moments in the history of the human race. Atahualpa, the divine ruler of the Inca Empire, the largest and most advanced of the New World countries, met there with Francisco Pizarro, the representative of Carlos I, King of Spain.

Atahualpa, in the heart of his empire, arrived at the meeting surrounded by an 80-strong battle-ready army. Pizarro, deep in the heart of a distant land, out of reach of any possible reinforcements, arrived at the meeting accompanied by 168 exhausted Spanish soldiers. The meeting started as well as can be expected from such a meeting. But after Atahualpa contemptuously threw down the Holy Scriptures offered to him by the Pope's representative in the New World, Pisaro gave the signal and the Spaniards stormed. By daybreak, 7,000 Indians were slaughtered without a single Spaniard falling. Only after dark did the massacre stop. Atahualpa was dragged in his rescuers and held captive for eight months. In exchange for his release, Pisaro demanded the biggest ransom in history - a large room full of gold.

The ransom was paid in full, which didn't stop Pizarro from executing Atahualpa anyway. A few decades later, the three great civilizations of the New World - the Incas, the Maya and the Aztecs - collapsed under European pressure. Two hundred years later, 95% of the population of the two American continents also became extinct.

In his book "Guns, Germs and Steel" Jared Diamond tries to find out why all this happened. Why did the Spanish win such a decisive victory despite their vast numerical inferiority (500 to 1)? And in general, why was it Pizarro who came to Lachamarca and captured Atahualpa son of the sun, and not Clocoxina, it was Athualpa's talented chief of staff who came to Madrid and captured Charles V? The answer is important to him because it represents the key to understanding the defining event of modern times: the takeover of the white man (More precisely, the Europeans; more precisely, the Western Europeans; more precisely, the citizens of several small countries on the western edge of the land mass known as Eurasia) during the next few centuries on most of humanity?

This question is not new. Many scholars required it during the centuries that have passed since the discovery of the New World. "Guns, Bacteria and Steel" therefore joins a centuries-old discourse that discusses the reasons for the very different development of the various human societies. The book was published in 1997, spent a record period at the top of the bestseller list in America, won prestigious awards and was translated into many languages. Six years later, at the beginning of another violent turn in the struggle to preserve Western dominance, this time against Islam, this important book is made available to the Hebrew reader courtesy of Am Oved's Ofakim Library.

The vicissitudes of time we have passed since 1997 oblige us to place "guns, bacteria and steel" in its original context. The decade in which the book was published saw Western culture at its peak. The communist evil empire fell apart, militant Iraq was trampled in an unprecedented show of unity, the stock markets soared, and the culture of capitalism was carried on the wings of the network and satellites to all corners of the earth. Faced with this unprecedented refinement of their culture, the intellectuals in America during the 90s wrestled with the big question: Is it all due to merit or grace?

The opening shot of the debate was fired by Francis Fukuyama, in his book "The End of History and the Last Man" (1992). Liberal democracy, according to Fukuyama, in the twentieth century trampled all competing methods of government - from monarchy to fascism and communism, of course - because it is the highest level of the political system; A system without internal contradictions of the kind that brought down its competitors, and therefore also the end point in the political development of the human race.

The question why Europe and not, for example, China or India (its main rivals in the 16th century) was also at the center of the historian David Landes' book Some So Poor", 1998). "The Wealth and) Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and the Reason for Western Supremacy , according to Landes, here is first and foremost cultural. Success came to a society that demonstrated diligence, self-discipline, rejection of gratification, initiative and openness to innovations - characteristic features, as the sociologist Max Weber claimed a hundred years earlier, of Western culture.

Among the political and cultural explanations, the genetic explanation also reared its ugly head. Richard Herrnstein, a professor of psychology from Harvard, and Charles Murray, a conservative publicist, claimed in their book ("The Bell Curve", 1994) that the level of intelligence is (mostly) innate, that it is directly related to success in life, and that it differs between the different races. Their conclusion was that the more the initial conditions are equal, the more social and economic success becomes an innate trait. From these cautious academic formulations the path is short to the conclusion that biology is fate, and that the decline of the inferior races is predictable.

The left pole of the debate was defined by Samuel Huntington in his book "The Clash of Civilizations" (1997), which came out with a sharp criticism of the arrogance of the heart of the West and warned it against rude interference in the affairs of other civilizations. Not only has history not ended, he warned, but we are facing a new phase in which cultural and religious differences will replace political and ideological differences as the source of contention and place the three great civilizations - the West, Islam and China - on a collision course whose results could dwarf all the bloody struggles of the twentieth century As much as they were.

"Guns, Germs and Steel" completed the opening five of the 90s and corresponded with all the positions mentioned. In the manner of great theses, Diamond's argument is simple and no different from that of the typical Tel Aviv real estate agent: the destinies of human beings are determined by three factors - location, location, and once again location. That is, the histories of the different societies followed different paths not because of biological differences (Diamond rejects the genetic argument with disgust as a racist and despicable argument) but because of differences in the environments in which they developed: the location of the continents, their topography, the climate, the vegetation, the population of animals and bacteria. These are the independent variables with the help of which human history must be understood, and all the rest: religions, governments, institutions, cultures, technologies, and geniuses are nothing but by-products that depend on them.

It is no wonder that Diamond, a professor of physiology at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine, who specialized in the study of the evolution of the birds of New Guinea, has been accused of geographic determinism, a charge that is as serious as any in the current academic climate. The days of simplistic explanations that the Industrial Revolution happened in Britain because it had coal are indeed gone, but Diamond's book cannot be dismissed so easily. It can be called by many names, but "simple" is not one of them. The explanations he offers are supported by a large number of findings, distinctions and theories from a wide variety of disciplines: archaeology, botany, zoology, molecular biology, genetics, linguistics, agriculture, ethnology, and more. All these are woven in his confident hands into one large and impressive argument presented to the reader in a fluid and clear style.

The book consists of four parts. The first part, "From Eden to Kahmarca", goes back 13 thousand years, to the end of the Ice Age, to describe the point in time when all human societies began their journey equally, as ignorant gangs of hunter-gatherers equipped with stone tools. Two examples are given afterwards - the meeting in Cahmarca between Pizarro and Atahualpa, and the description of the different human societies in the Polynesian islands - to illustrate for us the dramatic differences that can be created over time, even between neighboring cultures, under the influence of the environment.

The second part: "The rise and spread of food production", analyzes the cards that nature dealt to the various human societies. This is the original and the best among the parts of the book. In the animal kingdom, according to Diamond's calculation, there are only 148 species of large animals that can be domesticated, of which, if we ignore football fans for a moment, humanity has managed to domesticate only 14 species. Similarly, only a few hundred of the 200 species in the plant kingdom yield an amount of protein that justifies their cultivation. The event happened and the ancestors of almost all these animals and plants - pigs, cows, sheep, rice, wheat, etc. - developed in Eurasia, mainly in the Fertile Crescent region. The case also happened and of all the continents, only Eurasia rests on an east-west axis that stretches it on the same latitudes, which allows for a uniform climate in most of its territory, and therefore an easy spread of the plants and animals in its captivity, the basis for prosperity and wealth.

The third part of the book: "From food to guns, bacteria and steel" analyzes how the biogeographical advantages detailed in the previous part put societies in Eurasia on a different path than those in Australia, Africa and the two Americas. These advantages made possible an abundant food yield, which fed an ever-growing population, which created technology, which supported a complex culture, which created more technology, which created more abundance, and so on, in a process of increasing and increasing feedbacks that fed each other. 12 and a half thousand years after the Ice Age, the Eurasian societies had already developed a script, immune to violent bacteria, technologies based on metals, professional armies and a centralized government that allowed some of them (the Europeans) to engage in the conquest of the other societies, which did not enjoy similar opening conditions. This is the weakest part of the book. The analysis of the interactions between bacteria and human society is instructive, and the description of the development of writing and its social importance is one of the best I have read. Nevertheless, the ambitious attempt to reduce human culture to its biogeographic elements does not fare well and reads more like a caricature than a serious attempt to understand the complicated human history.

In the fourth part of the book, "Around the World in Five Chapters", Diamond returns to his home turf and applies the theory he developed in the previous parts to study cases in Australia, New Guinea, East Asia, Austronesia (the area of the Pacific Ocean that stretches from Madagascar to the Easter Islands) and Africa. The result, like other significant parts of the book, is fascinating and instructive. The epilogue, "The future of human history as a science", disappoints again. The challenge, according to Diamond, is to develop the history of man as a science equal in status to recognized historical sciences such as astronomy, geology and evolutionary biology. This is a dubious challenge. The fashionable attempt to base the orders of human culture on one or another "natural order", as represented by authoritative scientists, even those seeking political correctness, is no less problematic than the genetic explanation that elevates biology to the level of fate.

This is also a misguided challenge. The actions and ideas of men, the bread and butter of historians, may seem from Diamond's point of view, which encompasses entire continents and thousands of years, as tedious and unimportant curiosities. However, humans affected the nature around them no less than it affected them. Although human societies developed under environmental constraints, they repeatedly found ways to overcome them. All this does not diminish the value of "Guns, Germs and Steel" as an original and important book for anyone interested in the great patterns of history.

To the page of the book Guns Bacteria and Steel on the Mythos site

Dr. Tal Golan is a member of the Ben Gurion Heritage Center, Ben Gurion University

One response

interesting