Why do cells refuse to die - and how can research in the field be harnessed to treat old age diseases?

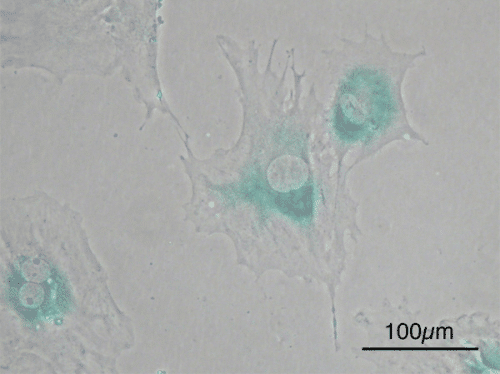

One of the changes that occur in the body as it ages is the gradual accumulation of certain cells. These "aging" cells (Senescent Cells) - which "retire" and stop dividing, but do not die - are always present and even play some important roles in the body, for example in wound healing. But in aging organs, these cells are not eliminated at the proper rate, and can accumulate and cause damage. Dr. Valery Krizhnovsky from the Department of Molecular Biology of the Cell at the Weizmann Institute of Science revealed the connection between these cells and diseases characteristic of aging and indicated a possible reason why they refuse to disappear. His research not only offers new insights into the aging process, but also points to new treatment directions for these diseases.

The study of cellular aging has greatly accelerated in recent years, due to findings that indicated that removing such cells from different areas of the body may stop certain aspects of the aging and disease processes. The pharmaceutical industry is also paying attention to research that may lead to the development of drugs that act against aging cells in certain organs or tissues.

When they are present in small amounts, these cells can prevent tumors from developing, help wounds to clot and start the healing process," says Dr. Krizhnovsky, "but when they accumulate, the result is inflammation and even cancer"

Dr. Krizhnovsky and his research group are engaged in basic research, which they conduct in human cell cultures and in mice, while trying to find out the relationship between aging cells and the body's aging processes. Are these cells, for example, the main cause of age-related diseases, or are they side effects? And why don't the cells die, even though they are damaged, so that the "cleaning teams" of the immune system can eliminate them?

The researchers hypothesized that the answer to the second question may be found in a family of proteins that regulate the process of cell suicide, known as apoptosis. They identified two proteins in this family that prevent apoptosis and that were produced at increased levels in aging cells. When mice with large amounts of senescent cells were injected with molecules that inhibit these two proteins, the cells underwent apoptosis and were then eliminated, and this led to an improvement in the condition of the tissue.

"When they are present in small amounts, these cells can prevent tumors from developing, help wounds to clot and start the healing process," says Dr. Krizhnovsky, "but when they accumulate, the result is inflammation and even cancer."

It seems that diseases that are common in old age are related to this cellular accumulation, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and Dr. Krizhnovsky hopes to apply the group's findings in research that will focus on the treatment of these diseases. "The trick", he says, "will be to focus on the aging cells without causing unwanted side effects". To this end, he is involved in developing models for COPD in mice and examining the possibility that removing senescent cells from the lungs alone may prevent or alleviate the disease. company "ידע", the applications arm of the Weizmann Institute, is working with Dr. Krzyznowski to register and commercialize patents for his discoveries.