Scientists from the Weizmann Institute have discovered that cells of the immune system grown in a low-oxygen environment eliminate cancer cells more efficiently

Training in a low-oxygen environment, for example at high altitude, can be beneficial not only for athletes and mountain climbers. It turns out that this type of "fitness training" can also improve the performance of the cells of the immune system that fight cancer. in a study which Recently published in the scientific journal Cell reports, Weizmann Institute scientists have shown that T cells of the immune system eliminate cancer cells more effectively after they are deprived of access to oxygen.

Activating the immune system against cancer - an approach known as immunotherapy - has been successfully implemented in recent years and is already saving the lives of many patients. In one version of the treatments, T cells are extracted from the patient's blood, increase their ability to identify and destroy tumors - and return them to the body. This method has already proven to be effective against certain types of blood cancer and cancer of the lymphatic system, but not against solid tumors. The reason for this probably lies in the low concentration of oxygen in these tumors - between 0.5% and 5% of all gases in the intercellular fluid - very little compared to most healthy tissues, and certainly compared to laboratory conditions, where the concentration of oxygen in the fluid in which cells are grown is about 20 %.

The tumor cells themselves are not bothered by the lack of oxygen: they manage to make optimal use of glucose, the main cellular fuel, even in a low-oxygen environment. However, under these conditions the T cells have difficulty penetrating the tumor and fighting the cancer. "Assassin T cells are the infantry of immunotherapy - they are the ones that destroy cancer cells, but they don't always succeed in carrying out their mission," says the head of the research group Prof. Guy Shahar from the Department of Immunology. In the past, studies have shown that growing T cells under oxygen-deprived conditions improves their ability to kill other cells in vitro, but it has never been tested whether these cells actually fight cancer better.

Just as humans develop higher endurance due to training in a low-oxygen environment, so too do T cells 'strengthen' as a result of 'fitness training' in this environment and become more effective assassins."

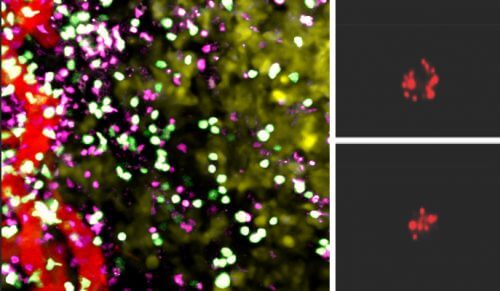

In the new study, research student Yael Gruper and staff scientist Revital Zahavi Pepperman from Prof. Shahar's laboratory - in collaboration with Dr. Tomer Meir Selma and Dr. Ziv Porat from the Department of Life Sciences Research Infrastructures and Dr. Tali Shalit from the Israeli National Center for Personalized Medicine at Grand - The T cells underwent a type of "training" in a low-oxygen environment: they grew the cells in an incubator with an extremely low oxygen concentration - only 1%. After that, the scientists divided mice with melanoma tumors into two groups: one group was treated with immunotherapy using normal T cells, and another group - using T cells grown in a low-oxygen environment.

The T cells that were grown under a lack of oxygen were much more successful in their fight against cancer. The mice treated with these cells stayed alive longer, and their tumors shrank much more dramatically than mice treated with normal T cells. Surprisingly, the T cells that were denied access to oxygen did not penetrate the cancerous tumor "better" than the normal cells. The secret of their success probably lay in the fact that they contained a larger amount of the enzyme called "granzyme B", which penetrates into cancer cells and kills them. Says Prof. Shahar: "Just as humans develop higher endurance thanks to training in a low-oxygen environment, so too do T cells 'strengthen' as a result of 'fitness training' in this environment and become more effective assassins."

If future studies lead to similar results using human T cells, it may be possible to improve immunotherapy and fight solid tumors as well. Prof. Shahar explains: "In any case, in certain types of immunotherapy, T cells are found from the patient's body and grown in the laboratory. Growing them under conditions of lack of oxygen is not a complicated thing, but this small change may significantly improve the effectiveness of the treatment."