Weizmann Institute scientists have uncovered a gene involved in a rare degenerative disease of the nervous system - which is related to the cellular waste removal mechanism

About 150 years ago, in the Augustinian monastery in Brno, Czech Republic, the monk Gregor Mendel conducted his elegant experiments with pea plants, and formulated the basic laws of heredity, which are named after him. The same rules, which determine the color of the flower or the height of the pea bush, also dictate the appearance of certain genetic diseases in humans, called "Mendelian diseases". Mendel did not know what is the factor that carries the traits from generation to generation. Nowadays, when the same factor is known as "gene", scientists invest a lot of effort to identify the genes involved in about 4,000 Mendelian diseases.

Research carried out by scientists from the Weizmann Institute of Science, in collaboration with doctors at the Sheba Hospital in Tel Hashomer, recently led to the discovery of the gene responsible for one of those diseases, which causes paralysis from birth. The research findings also reveal that the disease is related to a disruption in the activity of an essential protein, which participates in a process called autophagy, the main purpose of which is the "removal of waste" and the recycling of proteins in the cell. In doing so, this study joins a growing chain of evidence regarding the relationship between autophagy failures and neurodegenerative diseases, including common diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

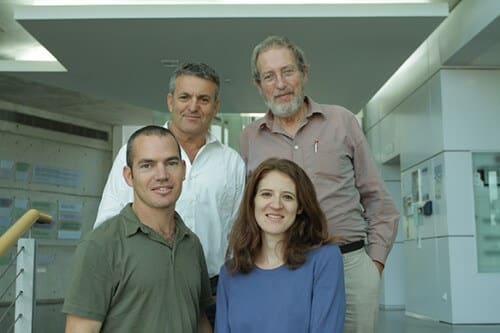

The Mendelian disease in question, HSP, is a rare degenerative disease of the nervous system, characterized by paralysis of the lower limbs, and significant damage to the nervous system, including mental retardation and breathing difficulties, which may cause death. The children's neurobiology department at the Haim Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer, under the direction of Prof. Baruria Ben-Zev, received a number of children, all of Bukhari descent, who, along with the familiar symptoms of HSP, also suffered from severe respiratory arrest. Prof. Ben-Zev hypothesized that this is a new and unknown subtype of the disease. At this point, Prof. Doron Lantz and research student Danit Oz Levy, from the department of molecular genetics at the Weizmann Institute of Science, entered the picture. The scientists received genetic material from four sick children (from three different families), and in collaboration with scientists from Duke University in North Carolina deciphered their DNA sequences, using advanced sequencing methods.

After receiving the sequencing results, they compared the DNA sequences of the patients with those of healthy people, focusing on rare mutations. This is how they were able to identify a mutation in an unknown gene, called TECPR2, which causes the protein produced from this gene to break down quickly, and in fact does not function. All the sick children carried two copies of the mutation, while in the genome of their parents - carriers of the disease - a single copy of it was found. This situation corresponds exactly to what is expected in the inheritance of a Mendelian disease of the "susceptible" (recessive) type: a pair of healthy parents, each of whom carries one copy of a "diseased" gene, which is not expressed due to the existence of a "healthy" copy, may bequeath to their child a second "Sick" copies of the gene, and then the disease appears. This fact strengthened the confidence of the scientists, that the mutation they identified is indeed involved in the disease. Further reinforcement of this assumption was received in a case a few months later, when another sick child suffering from similar symptoms was found. A genetic test showed that he carries a different mutation - which also damages the TECPR2 gene, and prevents the production of the protein.

The role of the TECPR2 gene was unknown. An extensive genetic scan, done using the GeneCard genomic database, developed by Prof. Lantz, brought up a single mention of the gene, linking it to the autophagy process. In this process, which is researched in the laboratory of Prof. Zebulon Elazar, in the department of biological chemistry at the institute, the cell produces small organelles, like bubbles, whose contents are transferred to the lysosome - the cellular "recycling wing". The process of autophagy is essential for the survival of the cell and its normal activity, in particular when it comes to delicate and complicated cells such as nerve cells; Disruptions in it damage the normal functioning of the nerve cell, and have been linked in the past to degenerative diseases of the nervous system.

In order to prove the connection between the mutation in the TECPR2 gene and the disease HSP, Prof. Lentz and Danit Oz Levy teamed up with Prof. Elazar and the research student from his group, Amir Gelman. The scientists took cell samples from two patients, and provided them with a smaller amount of food than needed. Such a state of starvation usually causes an increased activation of autophagy, with the aim of utilizing the cellular content for reuse. And yet, when testing two proteins known to participate in autophagy, it was found that the amount of one of them is smaller than normal - something that indicates damage to the mechanism. When they induced targeted silencing of the TECPR2 gene in healthy cells, a similar result was obtained.

The research findings reveal for the first time the gene responsible for a severe neurological disease, and point to the involvement of the autophagy mechanism in the HSP disease. The joint team continues the research, with the aim of better understanding what role the TECPR2 gene plays in the autophagy process and in the development of the disease. Prof. Lantz: "This study is an example of other studies in which the institute's scientists contribute to the developing field of 'systems medicine': a successful combination of medical genetics and systems biology."