The institute's scientists reveal how cancer leads to fatal emaciation and point the way to treatment

In our daily life we often tend to make a mistake and think that the same solution will get us out of different situations. This failure is also manifested in the body: when cells in our body are damaged, the immune system rushes to send white blood cells to the site of the injury and inflammation develops. This is indeed the correct solution for treating situations such as injury, but when systemic inflammation develops in response to a cancerous growth, it may be harmful. In a new study published recently, Weizmann Institute of Science scientists reveal that the inflammatory response allows cancer to change the metabolic processes in the patient's body, and it may even lead to a state of fatal emaciation. The scientists also show that it is possible to predict the weight loss in the early stages of the disease and even suggest a possible treatment.

In order to grow without control, cancerous tumors need a continuous supply of nutrients, including sugar, amino acids, fatty acids and nucleotides. Nucleotides - the building blocks of DNA - are used by cancer cells to replicate their genetic code and reproduce. Previous studies have found that the cancer obtains the substances it needs through reprogramming the metabolic processes in the tumor and its microenvironment. Therefore, already today, the treatment of cancer patients combines drugs that inhibit metabolic processes in the cancer's immediate environment.

However, in recent years, the understanding is taking shape that cancer affects not only the metabolic processes in its immediate environment, but also its macro-environment - that is, the patient's entire body. This effect has devastating consequences such as drug resistance, the formation of metastases, and also dysentery - a condition in which a dying patient rapidly loses body weight and does not respond to high-calorie food. Respecting a central role in the body's metabolism and detoxification from the blood, it senses and responds to any change in the levels of substances in the blood and tries to balance them. Fatal emaciation occurs when this metabolism goes out of balance, and the question is whether, how and when a cancer outside the liver manages to cause changes inside the liver - and what does it gain from this?

This issue was the focus of the new study, led by Omer Goldman from the research group of Prof. Ayelet Erez in the department of molecular biology of the cell at the institute. To test it, Goldman used models of breast cancer and pancreatic cancer in mice. He first followed the changes in the metabolic processes in the bodies of the mice with cancer, focusing on the urine substance that is formed from excess nitrogen that reaches the liver in the form of ammonia, and is excreted from the body through the urine.

""Currently there is no treatment for fatal emaciation which is a terminal stage of cancer. However, it is quite clear that in order to defeat the disease, it is not enough to damage the cancer - it is also necessary to strengthen the patient's body, which is required to fight it."

Excess nitrogen is a valuable resource for a developing cancer, as it can be used to create amino acids and subsequently proteins and nucleotides. In a previous study from 2018 Scientists from Prof. Erez's laboratory discovered, together with their colleagues, that in cases of cancer in children, instead of excess amino acids being broken down in the liver and eliminated in the urine, the malignant tumors manage to use them for their needs. As a result, the tumor grows, while the amount of urine produced in the liver and excreted in the urine is small.

In the new study, the scientists first looked at how and when the cancer affects the liver and what it benefits from inhibiting the urinary cycle. "A few days after the cancer began to develop, we detected a progressively worsening decrease in the activity of the 'infiltration cycle' and the levels of the enzymes that catalyze it," Goldman describes the findings. "As a result, a large amount of amino acid accumulated in the blood plasma of the mice, which in a normal state of health would have been broken down in the urinary cycle, and the cancerous tumor began to use it to produce nucleotides. In other words, the cancer changed the body's metabolism to feed itself. In addition, the accumulation of ammonia that was supposed to be removed in the urine, damaged the ability of the cells of the immune system to fight cancer."

The Trojan Horse of Cancer

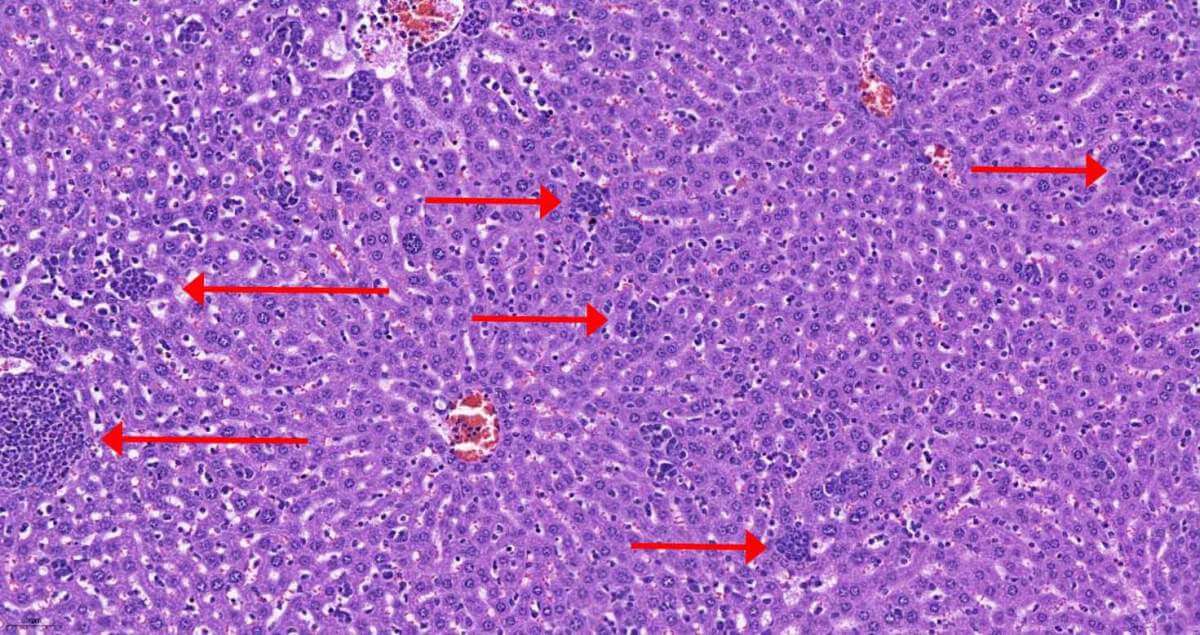

In order to reveal the mechanism of action by which the cancer reprograms the metabolic processes in the liver, the team of scientists first checked whether the composition of the cells in the liver changes. They discovered that already in the first days of the cancer's development, at the same time as the changes in the metabolic process appear, cells of the immune system infiltrate the liver. The scientists identified that it is mainly two types of white blood cells: monocytes, the mother cells of phagocytic cells, and neutrophils, whose role is to eliminate damaged tissues and bacteria. The scientists recognized that as the disease progressed, more mature and active monocytes and neutrophils infiltrated the liver. But how does the infiltration of white blood cells and the development of an inflammatory response lead to changes in liver metabolism?

In order to answer this, the scientists sequenced RNA molecules in liver cells during the progression of cancer in mice. The sequencing revealed that after the white blood cells penetrate the liver, a chain reaction occurs, at the end of which the cells stop producing the HNF4-alpha protein, which is considered the main controller of metabolic processes. Another process affected by the inflammatory reaction and the decrease in the amount of the visiting protein is the production of albumin - the most common protein in the blood which prevents the leakage of fluids from the blood vessels and the development of edema.

Stopping the production of the control protein and the accompanying decrease in albumin production, caused the mice to lose weight and may be an explanation for the phenomenon of fatal emaciation that makes it difficult for cancer patients to fight the disease as their condition deteriorates. But the research findings also inspire hope: the scientists used a method of gene therapy in order to cause the liver cells in mice with cancer to return and produce the control protein, thus stopping the progression of the cancer. After the treatment, the mice lost less weight and less fat tissue and suffered less edema. In addition, the cancer tumors themselves were smaller in these mice and their survival rates were higher.

Because the changes in metabolism occurred quite early in the development of the disease, the scientists hypothesized that different liver indices might predict which patients would develop fatal emaciation. The team developed a numerical index for liver function based on the results of a routine blood test for albumin and other blood components. When they ran the model on the databases of Klalit Health Services, the "Shiva" Medical Center (Tel Hashomer) and the "Suraski" Medical Center Tel Aviv (Ichilov), they discovered a correlation between the liver indices near the time of the cancer diagnosis and in the early stages of the disease and between weight loss and patient survival.

"Currently there is no treatment for the fatal emaciation which is a terminal stage of cancer. However, it is quite clear that in order to defeat the disease, it is not enough to damage the cancer - it is also necessary to strengthen the patient's body, which is required to fight it", says Prof. Erez. "The index we developed makes it possible to predict the loss of weight and to try and treat it from an early stage. I believe that the growing understanding of how cancer changes the metabolism of the patient's body, already at the beginning of the disease, as well as the genetic treatments that can prevent these changes, may in the near future pave the way for new drugs that will be integrated into the treatment plans of cancer patients already in the early stages of the disease."

Dr. Little Adler, Dr. Emma Hajaj, Dr. Naama Darzi, Sivan Galai, Hila Tishler and Jordan Ariab from the department of molecular cell biology at the institute also participated in the study; Dr. Tommaso Croza from the Department of Neuroscience at the Institute; Dor Lavi and Prof. Neta Erez from Tel Aviv University; Dr. Liat Aligor, Dr. Roni Oren and Dr. Yuri Kuznitsov from the Department of Veterinary Resources at the Institute; Eyal David and Prof. Ido Amit from the Department of Systemic Immunology at the Institute; Dr. Rami Ishak and Prof. Amos Tani from the Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics at the institute; Hani Stossel and Dr. Talia Golan from the "Shiva" Tel Hashomer Medical Center; Dr. Oded Singer and Dr. Sergey Malitsky from the Department of Life Science Research Infrastructures at the Institute; Dr. Renana Barak, Dr. Tamar Rubink and Prof. Ido Wolf from the Tel Aviv "Suraski" Medical Center; Prof. Roni Zager from the department of immunology and biological regeneration at the institute; Prof. Ann Saada from the Hadassah Medical Center and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Prof. Joo Sang Lee of Sengkyunkwan University in South Korea; and Prof. Shai Ben-Shahar from Klalit Health Fund and Tel Aviv University.