Yoram Sorek answers Shaul's question * The research, although it won the Ignoval Prize, has implications for understanding important processes such as bone fractures or bridges

From a mechanical point of view, dry spaghetti is a brittle substance, meaning hard and weak. Hard because it takes a lot of force to bend it and weak because it takes little energy to break it. It is the nature of such materials to shatter into small pieces when broken. Even the steel can sometimes behave as a brittle material as the passengers of the Titanic found out, to their disaster, when the metal shell of the ship went into a glassy state in the ice water and shattered instead of warping from the impact of the glacier. The truth is, Shaul, that two rather than one questions arise from your question: why would a piece of dry dough behave like glass and secondly why do such objects shatter into pieces instead of breaking in two at the peak of effort like a baguette or a bent wooden stick breaks?

Let's start with the dough: every pasta package worthy of its name boasts that it comes from semolina flour ground from durum wheat grains. The type of wheat is important because compared to other flours, durum wheat flour contains a lot of protein and it is this protein that gives the dry pasta its hardness and the famous al dente texture after cooking. When you add water to the flour and make the dough, bonds are opened that keep the wheat proteins in a folded state: the two main proteins: the glutenin (which gives the pasta rigidity and durability) and the gliadin (the flexible component) bind to each other and form the gluten (yes, the same protein that bothers celiac patients). The water and kneading arrange the new protein in long chains linked to each other by sulfur bonds: the same bonds that also give hardness to the proteins that make up our fingernails or the shells of turtles. A rigid network of protein fibers is formed: this is the stable structure that will prevent the spaghetti from turning into mush when cooked.

When you add water to the flour and put the mixture, you can actually feel the creation of the gluten with your hands: the point where the dough turns from a soft dough into a kind of rubber ball: this moment, which every baker knows, marks the formation of sulfur bonds and hydrogen bonds and therefore the transition of the protein from a collection of chains swimming in water to a structure with internal bonds that the fingers cannot separate but only bend. The second component: the starch that will turn into a soft and flexible gel during cooking is trapped at this stage as dense globules between the mesh fibers and therefore does not particularly affect the mechanical properties. The gluten is a very hydrophilic (water-loving) substance, therefore, during the drying phase when the water leaves the dough and moves from the center to the shell on its way out, the gluten will also move with it: the sides of the spaghetti stick will be especially rich in the hard protein and therefore especially crispy.

And now that we have made a hard stick dough, the second question remains: why does it shatter and not break in two?

The question does not sound particularly serious and indeed the physicists Basile Audoly and Sebastien Neukirch who studied the mechanism of breaking the spaghetti won the Ig Nobel Prize (the Hetoli Prize awarded for particularly strange or absurd research) for physics. This win, which puts their research in line with strange publications (such as the one that tested the attraction of Anopheles mosquitoes to the smell of Limburg cheese or Observation of necrophilia in a goose) does an injustice to the research topic that has implications for understanding important processes such as fractures in bones or bridges. Well, Saul, what really happens when you break a spaghetti stick?

When you bend the spaghetti, an arc is formed: in the outer part of this arc, the protein fibers are stretched and in the inner part, they are compressed. As the degree of curvature increases, the internal pressure increases and it is especially great in the center of the arch where the outer chains have to be stretched to the maximum and the inner chains have to be especially compressed. There, in the center, the first fracture will usually occur. We would expect that now that the two parts of the stick are aligned the tensioned spring will relax and we will be left with two sticks. But it turns out that the elastic energy stored in the stick is released as a wave that progresses from the breaking point to the ends of the stick.

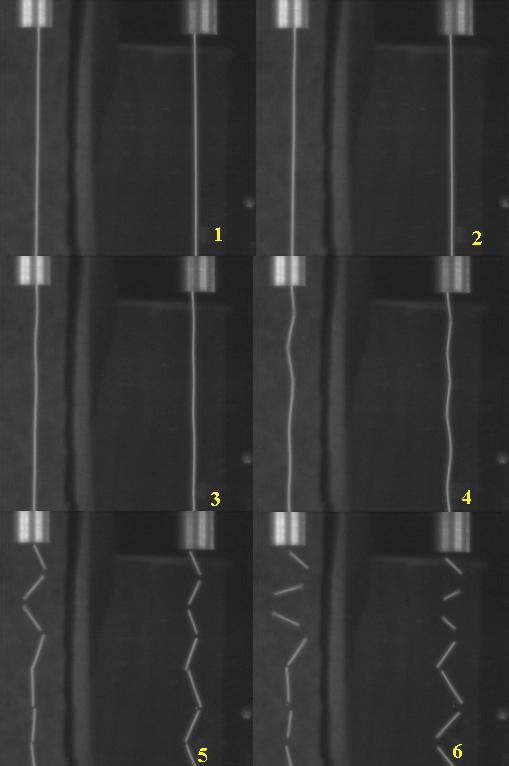

This waveform actually increases the bending by several points and therefore more fracture points will be created. When you break spaghetti sticks and check the distribution of the size of the fragments, it turns out that there is a physical sense in this crushing - most of the fragments are of the size corresponding to the distance of the peaks of the bending wave from the middle of the stick. In the series of photographs, the breaking of spaghetti is seen, this time not by bending but by a piston hitting one of its ends (each image shows photographs from two viewpoints at an angle of 90° from each other). Less than 100 millionths of a second separates each photo: you can see how a bending wave forms along the stick and how the spaghetti breaks at the peak points of this wave. Similar waves are probably responsible for the fact that a glass will always shatter into small pieces. If, instead of bending it or hitting it, you cook the spaghetti, the boiling water will open the bonds between the gluten chains so that their movement relative to each other is possible. Applying force will cause them to slide and flow and the spaghetti will tear into exactly two parts.

Thanks to Michael Higley and Andrew Belmonte for their help and permission to use photographs from their work.

11 תגובות

There is actually a way to break the pasta in half exactly, rotate the pasta around itself 270 degrees and bend at a speed of three millimeters per second

I'm afraid I have to ask another question bro

This article interested me almost as much as carob chocolate..:D

Yes, I want to shave, but not only with a mustache

Why not Mami?

Want to shave?

I have a question about the study: why <?

I liked the article about the spaghetti which was broken into unequal parts..

post Scriptum:

I am a friend of Israel

So true so accurate

Irony and humor are combined with fascinating research that no one dared to dream of

Shafu Yoyo

Nice article, a little note:

The Titanic sank in the direction of the steel spars nailed with cheap rivets - as a result of the blow the heads of the rivets broke

And several panels simply fell apart …..

Thanks to Yoram,

A real pleasure.

The last two paragraphs would have been enough.