While many scientists are looking for the answer in the cancer cells themselves, by comparing those that respond to chemotherapy and those that are resistant to it, Dr. Ravid Straussman and his colleagues thought that the key to understanding the problem lies elsewhere - in the functioning of the body's healthy cells.

"I always saw myself as a doctor," says Dr. Ravid Straussman, who holds a dual MD/PhD degree, and who recently joined the department of molecular cell biology at the institute. "But during the period when I finished my studies, I went and was drawn to research. And yet, even when I am engaged in research in the laboratory, my thoughts are given to the patient who needs treatment." The patients that Dr. Straussman is thinking about currently have very little hope for a cure, because the types of cancer they suffer from are resistant to chemotherapy. Why do some tumors shrink at the beginning of the chemical treatment, but refuse to disappear completely, while other tumors complete the process to the end, but return in a resistant version later? Why does it turn out that a treatment that completely destroys cancer cells in a test tube is much less effective in the human body?

Dr. Straussman began researching the resistance phenomenon of various types of cancer during his post-doctoral research at Harvard's Broad Institute and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In the laboratory of Prof. Todd Golov, the chief scientist of the Broad Institute and head of the cancer research program, he studied this question from an unconventional angle. While many scientists are looking for the answer in the cancer cells themselves, by comparing those that respond to chemotherapy and those that are resistant to it, Dr. Straussman and his colleagues thought that the key to understanding the problem lies elsewhere - in the functioning of the body's healthy cells.

The reason for this, he explains, is that cancer cells, like all body cells, are part of a large, sophisticated and interconnected system, in which various mechanisms are activated for mutual help and support. Healthy cells have the ability to call for help from distant parts of the body, such as the bone marrow, when they are damaged or under attack. The scientists suspected that, in a similar way, cancer cells call for help when they are under chemotherapy attack.

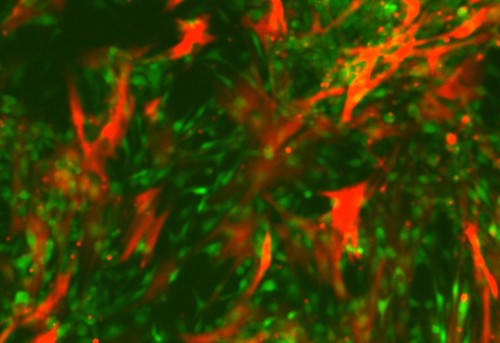

In order to test this hypothesis, the researchers grew different types of cancer cells, and tested their sensitivity to chemotherapy drugs. Indeed, they discovered that tumors that are examined in vitro and contain only cancer cells, are extremely sensitive to various types of chemotherapy. However, when different types of normal cells, normally found in the tumor environment, were added to the test tube, the sensitivity dropped - and in some cases even disappeared completely. After finding that this phenomenon occurs in many types of cancer, and in many types of chemotherapy drugs, the team decided to focus on melanoma - the type of cancer responsible for most skin cancer deaths. They discovered a protein that is secreted from certain healthy cells that are found in the tumor, and that protects the melanoma cells from one of the most advanced chemotherapy drugs currently used to treat this disease. The protein, which is a growth factor that affects liver cells (HGF - hepatocyte growth factor), plays other roles, including wound healing.

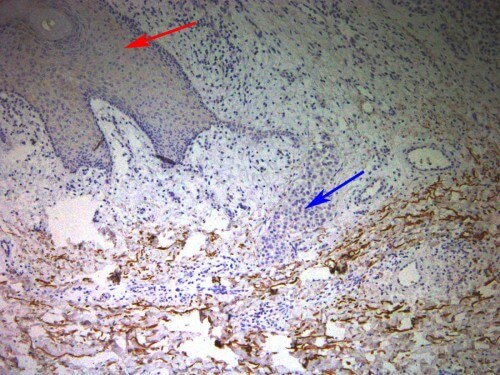

Later, the scientists looked for evidence of the protein's activity in tumor samples taken from melanoma patients. Then the results showed that when cells in the immediate vicinity of the tumor produced large amounts of HGF, the tumor showed resistance to chemotherapy, while patients where the cells did not produce HGF showed a much better response to treatment. This suggests that HGF, by itself, helps cancer cells survive in response to chemotherapy. Based on these findings, clinical trials are planned to take place soon in which HGF inhibitors will be given to melanoma patients, together with the standard chemotherapy treatment.

"A normal tumor contains different types of cells - both cancerous and normal," says Dr. Straussman. "The variety of normal cells found in the tumor's immediate environment may produce dozens of different substances, which help the tumor survive the chemotherapy treatment. We are at the beginning of the road in trying to understand what these materials are and how they help durability".

personal

Ravid Straussman was born in Ramat Gan, and served as an officer in the Air Force. He completed an MD/PhD course at the School of Medicine of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, in the laboratory of Prof. Shoshana Ravid. After a year during which he worked at the "Bilinson" hospital, he carried out post-doctoral research in the laboratory of Prof. Haim Sider at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He then went on to further post-doctoral research in the laboratory of Prof. Tod Golov at the Broad Institute. "Ravid, Cedar and Golov were mentors in the full sense of the word," he says. "It was a great privilege to work alongside them."

Ravid is married to Sharon, a children's endocrinologist, and has four children between the ages of 11 and XNUMX. In his free time he usually plays tennis.

2 תגובות

A logical and hopeful way of thinking for patients. One only has to ask how it was not thought of before.

Yehuda