In the first century AD, many Jews specialized in tannery - the production of leather products, for the Roman army stationed in the land, the Roman officials, the wealthy bodies and the foreign population mainly

The processing of animal skins using anti-oxidation substances so that they do not rot is called "tannery" in Sage sources as the term is taken from the Aramaic language. The employee is called "Borsi".

Here too, as in the previous industries, production increases due to the increased consumption by the Roman army stationed in the land, the Roman bureaucracy, the wealthy bodies and the mainly foreign population.

Anyone who chronologically compares texts in the Mishnah, the one dealing with the ancestors of crafts, with the Tosefta and the later Jerusalem Talmud, will immediately notice the picture that describes the development of tannery production throughout the generations, and indeed we will not be stunned by Rabbi Yehuda Hanasi's emphasis in a somewhat sweeping manner: Borsi" (Talmud Babili Pesachim Se p. XNUMX). Behind such a statement, and on the part of the president, hides economic encouragement from this and the stretching of the reference to two production avenues, each of which emits a completely different smell, as we will see later on. And maybe even an interesting insight into the world of production in general.

The tanners were mostly associated with the artificial-industrial production centers or villas (farms and ranches) such as in the Susita region, due to the geographical availability of sheep and goats.

Most of the leather items were made from "sheep hides", that is, stripped skins. These have undergone plant processing to prevent oxidation which causes decay. The stripper, including the artisan for working leather, is called "Shalha" and it is interesting to note that one of the artisans was none other than Rabbi Yossi ben Halfata, a famous and respected Tana.

This situation brings us to the conclusion that the relationship between the raising of sheep in the wild and in pens and the tanneries was multi-faceted, both in relation to the coarse cattle (sheep) and the thin ones (goats), which brought quite a bit of tension between the farmers and the shepherds, especially in the affair of the thin cattle breeding within the borders of the Land of Israel.

Among the tanners, the cobblers earned them a great reputation, and there is a double meaning in the period under discussion in the separation between the "shovel" that produces the complete shoes and the cobbler, and from the end of his name we learn about the certain Roman influence in his actual production. One of the famous cobblers was none other than Rabbi Yochanan the cobbler (although some insist, for some reason, that the origin of Rabbi Yochanan's name was none other than the corruption of the Hellenistic-Roman word Alexandria, and my teacher and Rabbi the late Prof. Shmuel Safrai will forgive me on this matter). In any case, if we compare the famous conditions of Rabbi Yossi ben Halfata and Rabbi Yochanan in the context of tannery work, we will reach an interesting conclusion in the context of the production and production of leather products.

Rabbi Yehuda Bar Ilai insists on a difference in the production of leather products up to his generation (the second half of the second century AD) and from his generation onwards, and we will understand this, of course, against the background of the large number of sheep raised during this period, which is substantiated by the evidence found in the "Cave of Tolls" regarding the high level of the production process.

Three types of sandals and some leather goods created by the Jews for the Romans

In my humble opinion, three sage testimonies testify to the matter of production for the Roman army and the Roman bureaucracy in Israel. First - the "nailed sandal" is, so it seems, the Roman military sandal for which the members of the Sanhedrin forbade wearing it on Shabbat. The origin of the prohibition created a debate among scholars, when some argued that the origin of the prohibition is simply not clear and therefore the sages suspended it in the laws of Shabbat, and perhaps because they did not simply want to explain the purpose of the prohibition. Some saw this as a social or even emotional reason, due to the connection of the myth of the "nailed sandal" to the revolt of the Jews against the Romans, when during the revolt of Ben Kusva (Bar Kochba) Jews hid in one of the caves and feared that one of them had betrayed the secret of their hiding to the Romans, and this was due to the fact that they noticed that the direction of his sandals was reversed at the mouth of the cave, and as a result they hurried to escape. The resulting commotion resulted in a terrible panicked and deadly escape. In any case, this is the "nailed sandal". Some argued that the purpose of the ban was security, when in the days of persecutions and decrees it was possible to distinguish, thanks to the ban, whether the combatants were soldiers of the Roman army or not. And perhaps, in my opinion, the "nailed sandal" is nothing but the military footwear, a kind of caliga, made by Jewish tanners for the Roman army, as well as the weapons of the Arab Revolt, which were also Kusba (approximately 132-128 CE, when the opinion of the sages was not comfortable with this and therefore they maintained the prohibition "To.

Second - the "valley sandal", such as was produced in the village of Amako near Acre, and where they allowed the thin animal to be raised, as well as in other somewhat special places.

Thirdly - "Dosta" or "rusta" is the coarse sandal of the farmers and lest its name be taken from the Latin - rusticus, we were rural.

Fourth - the various terms associated with service in the army on behalf of the tannery, such as "the dagger bag" (sheath), "the sword bag", "the preparation bag", "the house of the arrows" (arrow case), "the house of the fenders" for broad arrows, sheathing the bow, the bow and the spear and more .

The tanner's work naturally involved filth and stench, therefore the tanners' houses (factories) were removed from the city at least fifty cubits, that is, a little over 250 m, as well as, according to the Mishnah, the carcases and the cemeteries.

Moreover, the smell that stuck to the Bursi's clothes was so stinking that it was used as grounds for a divorce from the leather worker's wife. And so much so that sometimes they actually forced the divorce on the stock market. And the Talmud testifies to a situation in which a customer enters "the shop of a stockbroker and if he (the stockbroker) did not sell to him and did not take from him, he leaves and smells of himself and the smell of dirty clothes and his smell does not leave him all day" (Avot Darbi Nathan XNUMX:XNUMX).

And we will end with the saying of the Babylonian Talmud called Bar Kafra, in terms of closing a circle from the beginning of the chapter: "It is never possible without Basam (meaning a producer in the heavens) and without Borsi. Blessed is he whose art is with me. Woe to him whose art is stock exchange" (Bava Batra XNUMX p. XNUMX). A statement regarding a sigh of relief from this and a sigh of pain from this, as he said: This is the reality in which there is no way out.

At least three factors combined to clarify the development of the wood industry and its developments, and these are: the expansion of the construction era both in the city and in the countryside, the increase in consumption on behalf of the Roman army in Israel and the development of trade, especially the maritime trade of boats and ships.

It is true that the Land of Israel has known many damages in the area of land crafts mainly due to the damage to the trees during the rebellions against the Romans. Most of the damage was in Judea and a minority in the Galilee. However, this knowledge flourished from the second half of the second century AD onwards, and in the Osha generation after Shuch Mard Ben Kusava we hear that "they (foreigners) are not sold (trees) when attached to the ground, but they are sold when they are cut." Rabbi Yehuda says: "It is sold in order to prune (that is, to cut down or cut branches)" (Mishnat Avodah Zerah 8:XNUMX), and the Bereita in the Babylonian Talmud gives a taste in this regard: "Let our Rabbi: sell them (foreigners) a tree in order to prune, and prune, the words of Rabbi Yehuda" (Avoda Zerah XNUMX end of p. XNUMX). i.e. performs the action). President Raban Shimon ben Gamaliel testifies that "an idle tree is planted in the seventh" (Talmud Yerushalayim, chapter XNUMX, p. XNUMX) in terms of an alleged offense, but it is an idle tree intended for an interesting experiment in connection with the craft of processing wood products.

From the mouth of Rabbi Yehuda Hanasi we hear about the planting of many cedar trees in the area of Tiberias and Rabbi Levi testifies that it was very difficult, and in exaggeration - he could not see the area of Sodom due to the crowding of the firs that were planted there, and in this context it is said that these were used to build boats and ships that sailed south of the Jordan River and even in the north of the Dead Sea.

In order to back up the above, we emphasize that from the second half of the second century AD onward we witness the cultivation and cultivation of idle trees and idle plants on the one hand and evidence of artisan carpenters and their tools such as a chisel, a chisel, a chisel and a drill, a decorator, a sharpener, a chainsaw, a puller and a road and from In the findings, one can learn about carpentry products and its methods by examining evidence that indicates excellent technical knowledge. Prof. Yedin says that from the archaeological finds it is possible to learn about the technique of connecting planks and beams. According to him, three methods were customary in this regard: the first - connecting with pegs. That is, connecting flat panels on top of each other in a balanced way. The second - combining teeth. That is, connecting perpendicular panels to each other. The third - connecting tongues and holes. That is, connecting vertical beams. These methods are confirmed in Sage sources.

A tradition in the Jerusalem Talmud tells of "the seller of the flutes of foreign work is prohibited (but) if they would raise wages for the state, even if they are used for the purpose of foreign work, the seller is permitted" (Jerusalem Talmud Foreign Work Chapter XNUMX Mag p. XNUMX). First - we don't learn about them at all. Second - the economic necessity led to the legalization of everything related to foreign labor. Thirdly - this shows bilateral relations between Jews and foreigners at that time. Fourth - in general, we learn about production for the foreign population in Israel. Fifth - the economic torque of raising taxes to the Roman Empire, or to the local city, operated here. Sixth - we have before us an interesting testimony about a payment given by the craftsmen to the city authority which allows them in exchange for this money to rent a place (to rent or a stall in the market) as was customary in the Greek and Hellenistic polis.

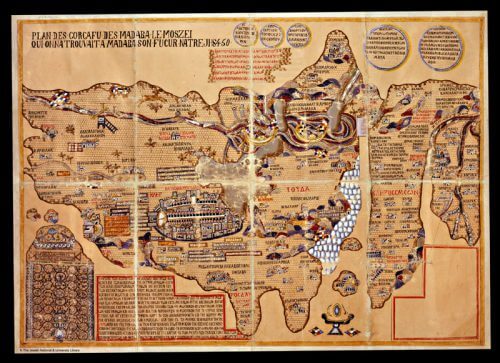

With the development of international trade and the Jews taking a part in it, we witness the building of ships in the workshops close to the port cities, such as in the Dead Sea (as appears for example from the deciphering of the mosaic of the Midaba map), where the kofer is found as a sealing material and in abundance, on the Sea of Galilee (such as in the fence and the tower of Zebeya), in Caesarea, in Dar , in Jaffa, Gaza and more.

2 תגובות

right. A writer's mistake, because the dimensions of the forearm are 56 cm. thanks for the correction

Error correction: 50 cubits (of removing the tanner from the city) is not 250 m but about 25 m. It turns out that this removal is intended to prevent a situation of permanent bad smell in the nearby city houses, but does not prevent the arrival of smell when the wind moves in the appropriate direction.