In the world of neurological twilight between sleep and wakefulness, hallucinations can become a tragic reality

Nothing seemed out of the ordinary about the man who arrived at the Minnesota Regional Sleep Disorders Center on June 27, 2005. Like thousands of other patients at the center, Benjamin Adyoyo (pseudonym) was a sleepwalker. Adoyo, a 26-year-old student born in Kenya, used to sleepwalk as a child, but recently the phenomenon has worsened. Adoyo got married in February and started waking his wife up at night. He shook her and jumped off the bed muttering incoherently. The frightened woman did her best to wake him up, but from the moment he awoke he remembered nothing. They lived in a two-room apartment in Plymouth, a suburb of Minneapolis, and the sleepwalking phenomenon caused tension in their new marriage. The referral form from Aduyo's family doctor states that the patient's wife "is sometimes frightened by his behavior, but she was not physically harmed."

After evaluation tests, the doctors at the sleep center asked Addoyo to return on August 10 for an encephalography (EEG) test that would monitor his brain waves while he slept. In the middle of the night, Adoyo began tossing and turning in bed, pulling the electrical wires connected to the electrodes and tearing strands from his hair while tearing the wires, but he did not wake up. The next morning, Michel Kramer Bornemann, the center's director, told Eduyo that the test was consistent with the diagnosis of a sleep problem known as "non-REM parasomnia." Bornemann told Edoyo about the removal of the electrodes and asked, "Do you remember a feeling of pain or the pulling itself?"

"No," Aduyo answered without hesitation.

Adduyo's next visit to the sleep center was on October 17. He said the anti-anxiety medication he was given by Bornemann to treat his sleepwalking was not helping, and Bornemann increased the dose from one to two milligrams. The doctor really hoped that he would be able to help his patient. "He was a very nice, friendly and captivating man," Borneman recalled. "I had no premonition that there was a single malicious bone in his body."

Adoyo did not return. Only a few months later, the sleep doctors discovered the reason for this. They received a letter from the Minnesota Public Defender's Office informing them that on October 19, just two days after his last visit to the clinic, Adoyo was arrested and charged with murdering his wife. "We are looking for someone to consult with regarding a possible connection of the sleep disorder to the murder," the letter said.

Sleep, maybe dream

The most basic and seemingly solid fact about sleep is that we are either asleep or awake. Although scientists divide the unconscious state into cycles of REM sleep (rapid eye movements) and NREM sleep (without rapid eye movements), and NREM sleep is even divided into three sub-stages, but overall, in the more than a hundred years that scientists have studied the phenomenon of human rest, they have worked on According to the assumption that sleep and wakefulness are two separate states with well-defined boundaries.

These seemingly firm boundaries are why judges and juries question claims that try to present a sleep disorder as a reason for committing a crime like Adduyo's. "I did it in my sleep" sounds like an unfounded legal claim that distorts scientific facts to absolve the accused of personal responsibility. After all, how can a person not be fully awake if they are capable of sexually assaulting, injuring or killing someone else? But over the past twenty years, sleep science has been revolutionized by a new theory that helps explain everything from sleep crimes to the basic nature of sleep itself. As Bornman puts it, "Sleep or wakefulness is not an all or nothing, black or white phenomenon. It occurs over a range.”

The idea that a person can be physically active but mentally disconnected is well known in popular culture, such as Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth who sleepwalked, and in courtrooms. The first time in the history of the American legal system that sleepwalking was successfully used as a defense in a murder trial was in 1846 in the trial of Albert Jackson Tyrrell, who killed a prostitute with a razor and nearly decapitated her. Closer to our time, in 1987 in Toronto, 23-year-old Kenneth Parks drove a distance of 22.5 kilometers and murdered his mother-in-law, allegedly while sleepwalking. In the end he wins.

Murder in one's sleep grabs headlines but is fortunately rare. In a review article from 2010 in the neuroscience journal Brain, 21 cases were detailed, and in about a third of them the defendant was acquitted. But non-fatal violent behavior, sex crimes and other crimes during sleep are more common than one might imagine. Approximately 40 million Americans suffer from sleep disorders, and according to a telephone survey conducted in the USA in the late 90s, two people out of 100 have harmed themselves or others in their sleep.

Borneman and his colleagues, Mark Mahwald and Carlos Schneck, are among the most prominent experts in the world in the field of sleep disorders, and they often receive requests for help from lawyers. In order to differentiate between their medical and legal work, in 2006 the doctors established a separate entity headed by Bornemann, in which Howald and Schenk serve as consultants. They call themselves the Sleep Crimes Forensics Office.

The Sleep Crimes Forensics Office operates like a scientific detective agency. Of the 250 cases that have come to his door so far, he has handled half for the prosecution and half for the defense. The agency doesn't just submit a medical opinion that supports the desired verdict, and it doesn't matter who pays for the service, but the doctors try to find out the truth. The title Borneman gave himself is "principal researcher," and he says that "in many ways I am drawing a neurological portrait."

The results of the investigations are unpredictable. "If I can disprove a defense based on an advertisement, the prosecutor can say, 'Now I have the possibility of conviction,'" says Borneman. But his work may also allow credit. "Real advertising-related behavior is done without awareness, intention, or motivation," says Borneman. "Therefore, from the point of view of a defense attorney, there is a basis for a complete acquittal." However, he knows that it is difficult for judges and juries to accept the idea of a sleeping interval. In the courtroom, not only the accused therefore stands trial, but also the very definition of recognition.

Awake but unconscious?

The essence of the theory known as the local sleep theory is implied by its name: parts of the brain can sleep while others are awake. If the theory is correct, it helps explain why people drive less carefully when they're tired or why sleepwalkers gobble up whole ice cream containers. She also explains the phenomenon of the "sexomaniacs", who grope their partners or even their children in their sleep. The concept of local sleep first appeared in the scientific literature in 1993 in a paper co-authored by James Kruger, now at Washington State University (WSU) in Spokane. At the time, the idea seemed heretical to the senior sleep researchers. "There's still something heretical about it," Kruger says, although proponents of the local theory are now an important and respected subset of sleep researchers worldwide.

The conventional wisdom was that sleep is a whole-brain phenomenon, and moreover, it has a central control mechanism that operates through regulatory circuits. But this view never seemed to make sense to Kruger. He says scientists already have evidence from other mammals about partial brain sleep. For example, dolphins doze with half their brain alternately and swim with one eye open. Kruger also reviewed the scientific literature on brain injuries in humans and found that no matter what part of the brain was damaged or missing, people always managed to sleep. This matter is not compatible with the existence of a centralized command center for sleep in the brain.

In a 2011 article titled "Use-Dependent Local Sleep" Kruger summarizes the alternative view that sleep is a distributed process that operates from the bottom up. "According to the new model, sleep is a property resulting from the joint output of smaller functional units in the brain," he wrote. Krueger and other researchers who hold the same opinion believe that different parts of the brain, neural networks and possibly even individual nerve cells go to sleep at different times, according to the amount of work they have done recently. (This is the reason why researchers describe sleep both as a local phenomenon, affecting different parts of the brain at different times, and as dependent on use, because it occurs only after a certain area has become sufficiently tired.) Only when most of the brain's neurons are in a sleep state does the characteristic state of sleep develop, i.e. Immobility, closed eyes, relaxed muscles. But long before that, tiny pieces of the brain are already dozing off.

Some of the most direct evidence for the local theory came from the lab of David Rector, a colleague of Kruger's at WSU. Rector works with rats and moves their whisker hairs in a precise and controlled manner. Each hair is connected to a specific column in the cerebral cortex, that is, to a group of hundreds of nerve cells that are closely connected and located on the surface of the brain. He inserts electrodes through the rat's skull into the cortical columns and can measure their electrical response to the movement of whisker hairs.

First, Rector determined the electrical response to moving hairs in two states, wakefulness or sleep, determined by the general behavior of the rat. Then he discovered exciting exceptions. "The findings that columns can be in a sleep-like state when the animal is awake, and conversely, columns can be in a wake-like state when the animal is asleep, suggest that sleep is a property of single cortical columns," Rector and Krueger reported in a 2008 paper.

Needless to say, humans don't like having metal electrodes inserted into their brains. Because of this, researchers have developed less direct experimental measures for characterizing people. In the study by Hans Van Dongen, another scientist at WSU, subjects looked at a computer screen and were required to press a button immediately when a reaction timer appeared. The instructions are to perform the task continuously for ten minutes, and the subjects' reaction time slows down as the task progresses. Such vigilance tests repeatedly activate the same neural pathways, and the increased use during the experiment actually forces them into a sleep state, Van Dongen says. He sees this as evidence of localized sleep rather than general fatigue or boredom because the subjects' level of performance immediately improves when they are allowed to switch to another task that uses a different area of the brain.

If people can be partially asleep while outwardly awake, then one can also consider the opposite proposition: that people can be partially awake while behaviorally asleep. This possibility would help explain a phenomenon that has puzzled scientists for a long time: people suffering from insomnia report after a night of monitoring in the laboratory that they "didn't sleep," even though the EEG measurements clearly show a brain wave pattern typical of sleep. In search of an explanation for this contradiction, Daniel Basie from the Institute of Sleep Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh performed a series of brain imaging studies at night in people suffering from insomnia. He concluded that while according to EEG and general behavior the subjects were asleep, their parietal cortex, where a sense of alertness is created, remained active during the night. In this sense, the subjects' reports of staying awake were accurate.

follow the clues

"What is going on there?" The central question of the 911 emergency line.

"Just come here," answered the man on the other end of the line shortly.

"You have to tell me what the problem is," insisted the operator.

"Someone's dead," said the man.

"Did someone die?"

"Yes."

"Where is she?"

"At her house. someone died Come here."

The call, received by Hennepin County 19 on October 2005, 3 at 41:XNUMX a.m., was from Benjamin Aduyo. He used his wife's cell phone, who at that moment was lying on the bathroom floor covered in blood.

When Aduyo's defense attorney reported the killing to the Bureau of Sleep Crimes Forensics, Borneman tried to uncover both the alleged criminal's guilt and the details of the crime. After the defense attorney briefed him, he read the police reports and the transcripts of Adduyo's interrogation conducted in the early morning hours after the murder. He even visited the apartment and arranged for a computer animation video to be made for him to help him reconstruct the events leading up to the murder.

The strange syntax of the 911 call was one of the first things that caught Borneman's eye. Aduyo did not say, "My wife is dead," says Borneman, but "Someone died." He did not say "in our house," but "in her house." In other words, Adoyo sounds like someone who just woke up.

There are, of course, alternative interpretations. Aduyo may have known he was guilty and wanted to reveal as little information as possible when he called 911. But when Borneman reviewed the police reports, he found no evidence of concealment or evasion. When officers from the Plymouth Police Department arrived at the scene, Adyo was waiting for them on the front steps. At the police station, after being read his rights, Adoyo confessed of his own free will to assaulting his wife, although he had difficulty in being precise in the details. "how is she?" he asked a police officer during one of the interrogation moments.

These initial findings, the mental disconnection in the call to 911, the revelation of the heart, the partial forgetfulness, made Borneman think that there is a possibility that Adoyo acted in his sleep when he killed his wife. But a judge or jury will question the science underlying such an explanation before they even consider an acquittal. Can someone really kill without knowing it while sleeping and if so, how?

In order to answer the question, one must first understand how sleep works in people who do not suffer from presomnia. The transitions between waking, REM and NREM states are based on hundreds of hormonal, neural, sensory, muscular and other physiological variables, says Mehwald, Bornemann's colleague. "Amazingly, these variables often cycle together, and there are billions of people worldwide who cycle between REM and NREM states many times every 24 hours." It is clear that there are islands of neural networks that are "awake" when the rest of the brain is asleep and vice versa, this is what the local sleep theory claims, but overall the transitions are clear.

However, in people with presomnia these thousands of variables are out of sync and the transitions between waking and sleeping states are mixed. The result, says Mehwald, is an extreme form of the local sleep phenomenon, in which the physical and mental characteristics of wakefulness, deep sleep, and dreaming overlap. The patients actually suffer from a condition where important parts of their brain disconnect while their body remains active.

Many cases reviewed by the Sleep Crimes Forensics Office show how disconnection can lead to criminal behavior. In late April 2012, for example, Borneman investigated the case of a soldier in the US Army who, when his wife tried to wake him up, he savagely hit her with his gun. After the fact he claimed that he had no intention of attacking her and that he did not remember doing so. According to him, he only remembers dreaming about using a knife to fight off a Nazi spy who attacked him. Bornemann believes that this is a possible example of a REM sleep disorder, in which the patient's muscles are not relaxed as is normally the case while dreaming, and therefore he is able to get up and physically carry out the scripts running through his mind.

Another case that Borneman investigated at the end of April 2012, concerned a wealthy businessman in Utah. One night, while he was sleeping, his 9-year-old daughter moved into his bed as she used to do when she had trouble falling asleep. The father woke up later and discovered to his horror that he was thrusting his pelvis towards her and his hand was touching her penis.

The businessman had no history of sexual offenses. After the incident, he underwent a psychological evaluation, was tested with a polygraph and even had the circumference of his penis measured while watching inappropriate images of children. No test has shown that he is a pedophile. Bornemann suspects that this behavior was due to arousal disorder, a subset of dissociative disorders, which includes sleepwalking, sleep eating, and sexomania. What all these conditions have in common is that they occur when there is an overlap between the neurophysiological features of NREM sleep and the complex motor abilities that characterize wakefulness.

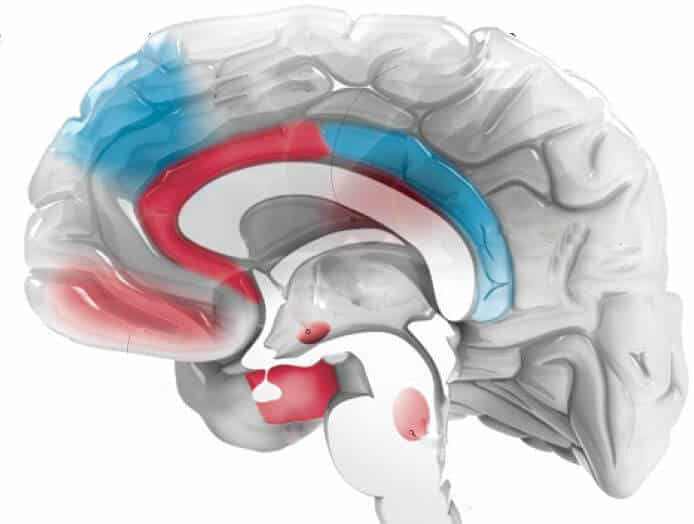

Accurately understanding which areas of the brain are active and which areas are dormant helps explain the perversions and violence that sometimes characterize Prosomnia patients. Brain imaging studies show that during NREM sleep the prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain located a little behind the forehead where logic and moral judgment are formed, is much less active than when awake. In contrast, the midbrain is active and capable of producing simple behaviors known as fixed action patterns. "These are essentially very primitive actions," says Borneman. "You can see standing, walking, attacking prey, eating, drinking, grooming and cleaning, and sexual or maternal behavior." The prefrontal cortex is supposed to inhibit such behaviors when they are inappropriate, but during NREM sleep this area of the brain retires from work. People are more like wild animals and are governed by instinctual drives and impulsive reactions.

Verdict

At the heart of the investigation by the Office for Criminal Identification of Sleep Crimes is the interview that Borneman conducts with the accused. Better face to face. The two questions that must be answered are whether this person has a true sleep disorder and whether, weighing all the other evidence, the sleep disorder could have been active at the time of the crime.

In the case of Adoyo, Borneman was in a very unusual situation: he had treated the defendant for a cold, so he knew that the young man was not faking a sleep disorder. The family members also vouched for the fact that Adoyo has been walking in his sleep since childhood. But the second question was more difficult: was Adoyo's sleep disorder the reason why he committed the crime? It could not be answered with absolute certainty because Bornemann cannot go back in time and enter Adduyo's mind to see what he was thinking during the murder. However, it is not easy to use sleepwalking as a bogus defense argument.

"The public believes that anything can happen from sleepwalking," says Borneman, "but only certain behaviors can occur, and generally for a limited period of time."

For example, "Physical proximity is key in many cases of sleep violence," says Borneman. The victims are often lying next to the prosomnia sufferer or are attacked when they try to wake him up. This was the case in the case of the soldier who dreamed of a Nazi spy as well as in the case of Perks, who drove from his sleep and attacked his family only after they tried to wake him up. Sleep crimes often have no explanation, no motive, and no characterizing the perpetrator, as in the case of the Utah businessman who raped his daughter.

During the interrogation of Adoyo, Borneman discovered that his former patient was not actually in close proximity to his wife before the attack. He fell asleep on the sofa and she is in the bedroom. He also stated that the violent outburst was not short and random, like most attacks during sleep, but rather prolonged and "managed", meaning that it involved several complex behaviors. First, Aduyo entered his wife's bedroom and attacked her with a hammer. He then chased her into the hallway outside the apartment and back into the bathroom. And finally he stabbed her and strangled her. "It is very unusual to see three mechanisms of violence from sleep" at once, says Borneman.

If any doubts remained, they were dispelled after Aduyo's confession that he had fought with his wife on the last day of her life and due to a report on this matter that Borneman read in the dead woman's diary. Aduyo suspected that his wife was having an affair with another man. He confronted her with what he perceived as proof, a condom in her laundry, before she angrily headed for her bed. In short, the crime did not characterize the defendant but was not without motive, and Borneman reported all of his findings to the public defender. Eventually, Aduyo pleaded guilty, and is now serving a 37-year prison term.

Bornemann, for his part, says he is not emotionally involved in the question of the guilt or innocence of the people he investigates. For him, his work allows him to conduct behavioral research on extreme sleep disorders that cannot be reproduced in the laboratory. The goal is to gather enough evidence to help change the attitudes of juries, judges and the general public, who still believe that consciousness is an all-or-nothing phenomenon. "The neurosciences have advanced far beyond the thinking patterns of the legal community," he says, "and the legal community must close the gap."

James Vlahos is a freelance journalist who has written for National Geographic, the New York Times and Popular Science.

in brief

Whether the brain is asleep or awake is not an all-or-nothing question, according to some scientists. Their research suggests that what we call sleep, that is, eyes closed, stillness, and unconsciousness, occurs only after several different areas of the brain enter sleep cycles.

If this partial sleep hypothesis is correct, certain areas of the brain may sleep while we are awake on the outside and vice versa. This new view may explain why, in extremely rare cases, people can commit serious crimes, including murder, in their sleep.

And more on the subject

Violence in Sleep. Francesca Siclari et al. in Brain, Vol. 133, no. 12, pages 3494-3509; December 2010.

Office of Forensic Identification of Sleep Crimes:

2 תגובות

Just for accuracy, encephalography simply means measuring the head, the emphasis in EEG is measuring changes in the electric field in the head, and the full name is electroencephalography