Another angle on the amazing finds discovered in Georgia that overturn accepted beliefs about the journey of the first hominids out of Africa

We will not stop investigating

And all our research will end

When we reach the starting point

And we will get to know the place for the first time

- T. S. Eliot, four quatrains: "Little Gidding"

Evolutionarily, the tendency to settle in new places is one of the features that distinguish us from other animals: our habitat is wider than that of any other primate. Humans were not always so cosmopolitan. The species from the human family - the hominids - remained within the borders of Africa, it is their birthplace, during most of their evolution, which lasted about seven million years. At some point, our ancestors began to leave their homeland, thereby opening a new chapter in the family history of all of us.

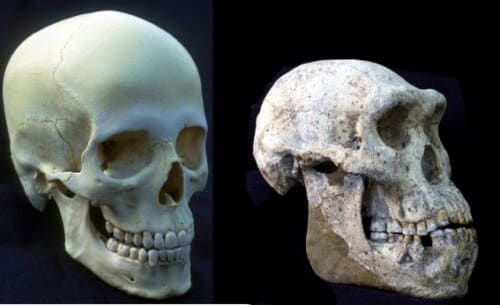

Until recently, this episode remained rather obscure and scarce in fossil evidence. Most paleoanthropologists, researchers of human fossils, concluded, based on a handful of humans from sites in China and the island of Java in Indonesia, that the first intercontinental journeys were made a little over a million years ago. The wanderers according to this opinion were earlier hominids in the development of the human race, known as "Homo erectus" (Homo erectus – the upright person). Homo erectus There were long-limbed and big-brained creatures, therefore able to cover distances and be sophisticated as pioneers are expected to be. Even earlier hominids, like Homo the abilis (Homo skill - The creator man (and Australopithecus)australopithecus) were mostly small in stature and brain, not much bigger than a modern chimpanzee. In contrast, the structure of Homo erectus already reflected the body structure of modern man.

- You will also want to read:

- A complete skull was discovered, which is the earliest evidence of human presence outside of Africa

- Evidence of the use of fire a million years ago

And with that, the first representatives of the gay Arctus In Africa, a group of hominids sometimes called Homo Argester (Homo ergaster), appeared already 1.9 million years ago. Why did it take them so long to leave? One of the explanations offered by researchers is that Homo erectus He could not have encrypted before the development of the hand ax and other symmetrical stone tools (these appeared in a technologically developed society called the Acheulean illusory culture). It is not clear what the advantage of these stone tools is over the shavings and the cutting and scraping tools of the earlier Oldubai period (named after the Oldubai Valley in Tanzania). They may have been more efficient for killing animals and cutting their meat. In any case, it is generally accepted that the oldest traces of humans outside of Africa are stone tools created with the help of the illusory chipping technique and discovered at the Obadiah site near Beit-Zare in Israel.

Muscular, resourceful, armed with state-of-the-art weapons - this was the hominid hero that Hollywood was casting for the perfect vanguard role. But it turns out to be too perfect. In recent years, researchers excavating the Dmanisi site in Georgia discovered a collection of exceptionally well-preserved human fossils as well as stone tools and animal remains. The remains date to a period of about 1.75 million years ago - almost half a million years before the remains from Obadiah. In paleoanthropological terms, this is a real treasure. Such a wealth of bones has not been discovered at any other hominid site in the world, and this has provided scientists with a first-of-its-kind peek into the lives and times of our hominid ancestors. The discoveries were revolutionary: the hominids from Georgia are much more primitive than expected in both their body structure and their technology, and they make experts wonder not only why early humans first left Africa, but also how they did it.

Doubtful start

Damanisi, today's sleepy village, lies at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains, 85 kilometers southwest of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia as the crow flies, and 20 kilometers north of the border with Armenia. In the Middle Ages, Damanisi was one of the prominent cities, and an important transit station along the ancient Silk Road. Because of this, the area attracted archaeologists who began as early as 1930 to dig among the crumbling ruins of the medieval citadel. It was only in 1983 that a find was discovered that hinted that the site had a deeper meaning. It was when paleontologist Absalom Vakva, a paleontologist from the Georgian Academy of Sciences, discovered in one of the pits used to store grain the remains of a rhinoceros, an animal that became extinct in the area a long time ago. The inhabitants of the citadel who dug the pits probably opened a window into prehistory.

The following year, during paleontological excavations, primitive stone tools were discovered that caused excitement due to the possibility of discovering fossilized human remains. Finally, in 1991, on the last day of the excavation season, the team found what they were looking for: a hominid bone, discovered under the skeleton of a sabre-toothed tiger.

Based on the age assessment of the animal remains found on the site, the researchers concluded that the bone - lower jaw, which they attributed to Homo erectus - She is about 1.6 million years old. And if this is indeed the age of the fossil, it is therefore the oldest hominid discovered outside of Africa. But when David Lordkipanidze and the late Leo Gabonia, also of the Georgian Academy of Sciences, showed the find to some of the most important paleoanthropologists during a conference in Germany that year, their claims were met with skepticism. Humans were supposed to have left Africa only a million years ago, and the well-preserved lower jaw, with all its teeth in place, did not appear as ancient as the Georgians claimed. Many concluded that the fossil did not belong to Homo erectus, but to a later species. And so, instead of the Damanisi jaw being approved by the paleoanthropological elite, it was met with skepticism.

The team members were not deterred, and continued to work on the site, delving into the geology and looking for other hominid remains. Their persistence paid off in the end: a few meters from the place where the jaw was found eight years before, in 1999 the workers found two skulls. The following spring, an article describing the fossils appeared in the scientific journal Science. "That year the celebration started," recalls Lordkipanidze, who is now managing the excavations. The findings established a close relationship between the Damanisi hominids and the African Homo erectus. Unlike the earliest humans found in East Asia and Western Europe, which had distinct regional characteristics, the skulls from Damanisi clearly resembled the previous African finds - for example, in the shape of the eyebrow bone.

At the same time, geologists were able to accurately determine the age of the fossils. The layer of sedimentary rock in which they were found is immediately above a thick layer of volcanic stone that has been dated by radiometric methods as 1.85 million years old. K. Reid Fring of the University of North Texas explains that the fresh, smooth contours of the basalt indicate that it was not long before it was covered by the sedimentary rocks containing the fossils. Paleomagnetic tests of the sedimentary rocks show that they were formed about 1.77 million years ago, when the magnetic polarity of the Earth turned over, a layer known as the Matuyama boundary. Moreover, remains of animals, known to be ancient, accompanied the hominid fossils, such as a rodent called Mimomys, which lived only in the period between 1.6 and 2 million years before our time. And finally, similar stratification features were found in another 1.76 million year old basalt layer that was exposed at a nearby site.

The combination of the new fossils and the dating results proved beyond any doubt that Damanisi is the oldest hominid site outside of Africa. This brought forward the date of the population of Eurasia by hundreds of thousands of years. The findings also debunked the theory that humans could not have left Africa before developing the illusionary chipping technique. Damanisi's toolbox contained only tools from the Oldouba period, fashioned from local raw materials.

Small pioneers

The ancient age of the hominids from Georgia and the simplicity of their tools have amazed many paleoanthropologists. But Damanisi had more surprises in store. In July 2002 Lordkipanidze's group announced that they had found a third skull, in almost perfect condition - including the lower jaw bone - which was discovered to be one of the most primitive hominid specimens at the site. The volume of the first two skulls was 770 cm650, and they contained 600 cmXNUMX of gray matter, while the volume of the third skull was only XNUMX cmXNUMX - less than half the size of the modern brain and much smaller than expected for Homo erectus. The shape of the third skulls also did not completely resemble that of Homo erectus. The fine forehead, the prominent face and the convex back of the skull, all these corresponded to Homo abilis, the ancestor of Homo erectus.

One of the surprising conclusions from the discovery of the third skull was that, contrary to the view that a large brain was a condition for the first intercontinental migration, Damanisi's findings show that the brains of some of those first nomads were no more developed than that of Homo habilis. Also, the bodies of the hominids from Georgia were probably not much larger than that of Homo habilis. Until now, only a few remains of body parts lower than the neck, such as ribs, clavicle, vertebrae, as well as upper arm, hand and foot bones, have been discovered, and they are still awaiting an official description in a scientific journal. But it's already clear that "these people were small," as team member J. Philip Reitmeier of Binghamton University argues.

"This is the first time we have found an intermediate stage between Arctus and Habilis," says Lordkipanidze. Although the team tentatively classified the fossils as Homo erectus, based on several characteristic features, they believe that the population represented by the Damanisi hominids is essentially a missing link between Homo erectus and Homo habilis.

Other scholars have proposed a more detailed classification. Based on the anatomical variation of the skulls and jaws found so far (including a giant jaw discovered in 2000), Jeffrey Schwartz of the University of Pittsburgh suggested that the Damanisi fossils may represent two or more human species. "Then I'll eat one of them," quips Milford H. Wolfoff of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who offers a more plausible explanation. In his opinion, the unusual jaw belonged to a male while the rest of the bones belonged to females.

While Lordkipanidze admits that the giant jaw "causes a headache," but explains that since all the fossils were found in the same geological layer, they probably belong to the same population of Homo erectus. According to him, one of the reasons for the importance of Damanisi is that the site "allows us to think about the meaning of the word 'variety'." There may have been researchers who underestimated the level of variation in the Homo erectus population - an opinion supported by new discoveries at a site called Bori in the Afar steppe in Ethiopia and another site called Eilert in Kenya. Lordkipanidze believes that as the picture in Georgia becomes clearer, many fossils from Africa will have to be re-evaluated, and the question of who the founding fathers of our dynasty really are. "Perhaps Habilis does not belong to the genus Homo at all," he wonders. In fact, some experts wonder if this hominid actually belongs to the genus Australopithecus rather than our own.

"The reasons that led to the assimilation of Habilis to the genus Homo are not very convincing," says Bernard Wood of George Washington University. Considering its brain and body dimensions, the characteristics of its jaw and teeth and its ability to move, "Abilis is more similar to Australopithecus than we thought." If true, the appearance of Homo erectus may have marked the birth of our species. It is still unclear, Wood says, whether the Damanisi hominids belong to the genus Homo or to the genus Australopithecus.

But apart from the taxonomic difficulty, the apparently small body structure of the Damanisi people raises additional difficulties among paleoanthropologists. According to a common belief that tries to explain why humans left Africa, presented by Alan Walker and Pat Shipman from the University of Pennsylvania and developed in the XNUMXs by William R. Leonard and his colleagues from Northwestern University, the larger Homo erectus needed better quality food than its smaller predecessors, food that included meat, To satisfy the growing energy needs of his body.. This nutritional regime forced the Homo Eractus to expand their habitat to find enough food, and so, according to propaganda, they migrated to Eurasia. The exact body dimensions of the ancient people from Georgia are still unknown, but in any case, the discovery of hominids significantly smaller than Homo erectus outside of Africa requires experts to re-examine this scenario.

Wonders of Georgia

Whatever the reason for the early hominids leaving Africa, it is not difficult to see why they settled in South Georgia. First, the Black Sea in the west and the Caspian Sea in the east guaranteed, obviously, mild and even Mediterranean weather. Second, the area seems to have been particularly ecologically rich: remains of forest animals such as deer, and steppe animals such as horses, were all found at the site and testify to the existence of a mosaic of forests and steppes. Thus, from a practical point of view, if conditions worsened in one place, the hominids did not have to migrate far to improve their situation. "Environmental diversity may have accelerated the population of the area," says Fring. And especially the occupation of the Damanisi site, which is on a rocky cliff at the confluence of rivers. The place was perhaps especially fortified due to its proximity to water which not only quenched the thirst of the settlers but also attracted hunting animals.

"Biologically, it was an eventful place," notes Martha Tappen of the University of Minnesota. Many of the thousands of mammal fossils unearthed in the excavations originate from large predators such as saber-toothed tigers, panthers, bears, hyenas and wolves. Tappan, whose work focuses on trying to understand what led to the accumulation of bones at the site, suspects that the predators used the cliff between the rivers as a trap. "The question is, if the hominids did the same," she says.

So far, Tappen has identified several incisions on the animal bones, indicating that the Damanisi settlers sometimes ate meat. But it is not known if they were satisfied with animals hunted by the animals of prey or if they hunted themselves. This question requires further research. One of the few hypotheses still accepted by researchers explains why humans were able to expand their habitat north. According to this explanation, the transition from a vegetarian diet, the majority of Australopithecus, to a hunter-gatherer diet, is what allowed hominids to survive the cold winter months, when plant food sources were scarce or unavailable. Only by further researching the mammal bones at the site will it be possible to understand how the Damanisi people obtained meat. But Tappen concluded that they were also hunters. "When you collect, the availability of the animals is very unpredictable," she notes. "I don't think that was their main strategy."

But this does not mean that humans were top predators. "They could have been both hunters and hunted," Tappen explains. Holes caused by an injury on one of the skulls and gnawing marks on the large jaw indicate that some of the hominids at Damanisi ended their lives as cat food.

The departure from Africa

The remains in Georgia prove that humans left Africa shortly after the development of Homo erectus, about 1.9 million years ago. But where they went after that remains a mystery. The oldest fossils in Asia, other than those from Damanisi, are still only a little over a million years old (although disputed sites in Java are 1.8 million years old), while the fossils in Europe are only around 800,000 years old. Anatomically, the Damanisi could certainly have been the ancestors of the later Homo erectus from Asia, but they could also have been sons of an extinct group, the spearhead of a wave of settlers that partially washed over Eurasia. Scientists agree that there were several waves of migration out of Africa as well as migration back to it. "Damanisi represents only one point in time," says Lordkipanidze. "We have to decipher what happened before that and what came after that."

To some extent, the findings at Damanisi raise more questions than they provide answers, a common phenomenon in paleoanthropology. "It's nice to shake up the existing conventions, but it's frustrating that some of the ideas that seemed so promising eight or ten years ago are no longer true," says Reitmeier. new ones They may have migrated north following the herds of vegetarian animals. Or it may have been the simple and familiar need to know what lies beyond the hill, or the river, or the grassy meadow - simply prehistoric wanderlust.

The good news is that scientists have only begun to explore the Damanisi site in depth. The fossils that have been discovered so far have been collected in only a small part of the estimated area of the site, and new findings emerge from the ground faster than the rate at which scientists can characterize them - a fourth skull that was discovered in 2002 is still in the stages of processing and characterization, and a new jaw, tibia and ankle were discovered in the summer of 2003. At the top of the fossil hunters' wish list are femur and pelvis bones that will allow the body dimensions of the early settlers to be calculated and find out how efficiently they could have migrated over great distances. And there is no reason why such bones should not be found. "Mountains of fossils may yet be discovered," Wolfoff enthuses. And Lordkipanidze agrees, "There is work here for many generations," noting that he can imagine his grandchildren working at the site even in a few decades. And who knows what limits humanity will break by then?

Excavations at Damanisi

Damanisi, Georgia, July - The village of Damanisi is only a two-hour drive from Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. Nevertheless, the feeling is that the village is in a world different from that of the bustling city choked with diesel fumes and dust. Here, at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains, there are more donkey carts than cars and the air smells of hay. The locals cultivate the rich soil and raise sheep, pigs and goats. In the summer, children run on homemade scooters on a section of paved road. Even the roosters seem to have stopped keeping track of time, and they call not only at dawn, but also in the afternoon and evening.

But the leisurely pace of modern life masks the region's glorious past. Centuries ago, Damanisi was a powerful center, due to its location at the intersection of the Byzantine and Persian trade routes. Today the area is littered with souvenirs from the past. Mounds that look like haystacks are revealed, at a closer look, to be ancient Muslim tombs; Heavy rain reveals burial sites from the Middle Ages on the hillside; And above all rise the impressive ruins of a citadel that was built of a cliff that once weakened the Silk Road.

This is what they knew about Damanisi's past for decades. But recently the researchers learned that long before the rise and fall of the city it was the living area of one of the primitive ancestors of man. This ancestor was, as far as is known, the first to leave Africa about 1.75 million years ago - much earlier than previously thought. This insight still beats David Lordkipanidze. Only a dozen years ago he helped discover the first hominid bone in Damanisi. After four skulls, 2,000 stone tools and thousands of animal fossils, the XNUMX-year-old Lordkipanidze is the deputy director of the National Museum of Georgia and he heads the excavation operation at Damanisi, an operation that many paleoanthropologists consider one of the most amazing in recent years. "It is very lucky to find these beautiful fossils," he says. But this is also a "great responsibility". Indeed, being both a paleontologist and a politician, Vardkipanidze seems to be working around the clock, conducting late-night conversations with research colleagues and potential donors on his cell phone.

Mainly thanks to these efforts, the research group that initially numbered 10 Georgians and Germans has grown into a collaboration between 30 scientists and students from around the world, some of whom gather here every year during the excavation season. For eight weeks every summer, the field team in Damanisi carries out surveys, excavations and analysis of finds. This is a low-budget operation. The team members live in a simple house a few kilometers away from the site, and usually four people sleep in a tiny room. Electricity is an occasional commodity at best, and running hot water is non-existent.

Every morning at around 8:30, after a breakfast that includes bread and tea on picnic tables on the balcony, the workers of the sleeping quarters drive to the site in a military truck left over from the days of the Soviet occupation. The main excavation site, a twenty-by-twenty-meter square, yielded in 2001 an exceptionally well-preserved skull with its lower jaw bone. Each team member is responsible for a plot of one square meter and carefully records the spatial location of each bone or other find uncovered during the excavations. These objects are tagged and kept in bags until they are investigated. Even unremarkable sediments and pebbles are preserved for further examination: washing and filtering them may yield shells, tiny mammal bones, and other important environmental clues.

Today the fossil hunters are in a particularly good mood. A rare bout of rain left them stranded at home yesterday [water-soaked bones are crunchy, and you can't dig them out], and the morning sky threatened to rain today as well. But the mist that enveloped the mountains finally faded, replaced by the sounds of diggers singing Johnny Nash's "I Can See Clearly Now," and the clicking and scraping of shovels, hammers, and knives against the limestone. They are moving slowly. The diggers are now working in the upper, dense layer, from which it is difficult to extract the bones and stones. They must be careful not to scratch the remains with their tools, so that in the analysis they are not mistaken later and think that the new scratch marks are ancient marks. At midday the diggers are happy for lunch - tomatoes, cucumbers, bread, hard-boiled eggs and salty cheese with a pungent smell [that you have to get used to the taste] - and for a light rest on the grass before they return to their work.

Meanwhile, in a makeshift laboratory in the camp itself, other team members are sorting through the remains brought earlier by the diggers. They sit at wooden tables with metal tops, share an old-fashioned microscope and identify the species to which each bone belongs and examine it for signs of fractures, cuts or teeth marks. This information will eventually reveal how the bones accumulated. Preliminary findings from the main excavation indicate that the saber-toothed tigers that lived in the area may have collected them. On the other hand, preliminary information from another excavation site marked 6M, suggests that humans were active there - that site has an abundance of shattered bones that are more typical of hominid activity than carnivore activity. If so, then 6M could provide crucial insights into the way the primitive hominids at Damanisi managed to sustain themselves in the New Land.

When the fossil hunters return with the day's loot at about four o'clock, the camp is again the center of activity. An early dinner leaves time for a shower, a game of chess or a trip down the road to visit the enterprising village that sells sweets, soda, cigarettes and other luxuries in a small whitewashed building affectionately called the mall. After that, there is an hour left for lab work and Arabic tea.

Lordkipanidze felt that he was closing a circle. Here, where he first experimented with paleoanthropology, he hopes to establish a leading field school to train young archaeologists who want to advance. In the meantime, he and his colleagues plan to look for hominid fossils at other promising sites in the area. Georgia may still hold big surprises.

Overview/ The first settlers

According to the popular opinion today, the first people who left Africa were tall, had big brains and were equipped with sophisticated stone tools and they started migrating north about a million years ago.

New fossils discovered in Georgia are forcing scientists to reconsider this scenario. The remains are almost half a million years older than the hominid remains that were previously considered the oldest outside of Africa. They are also smaller and accompanied by more primitive devices than expected.

Following these findings, the question arises: what motivated our ancestors to leave the land of their birth? They also provide scientists with a rare opportunity to study not just one representative individual of the early Homo species, but an entire population.

4 תגובות

Paragraph 2: Homo erectus can swallow, not swallow, distances

What is the chance that the large jaw is actually a genetic mutation similar to today's Down syndrome?