Archeology and the controversy over historical truth in the Bible. Following the polemical book on historical truth in the Bible, edited by Israel L. Levin and Amichai Mazar, Yad Ben-Zvi Publishing House in collaboration with the Dinor Center, Jerusalem, 2001

Itamar Singer

This title, but without the question mark, is borrowed from the Hebrew translation of a book published in Germany in the 1955s under the title "And yet the Bible is right" (originally 1958 Werner Keller, The Bible as History, published by Hebraut Seferat XNUMX). It was a fairly routine review of archaeological discoveries from the ancient Near East that support the biblical story, a book that many like it were written before and after. However, the provocative title and form

The comprehensible writing made the book, which was translated into dozens of languages, one of the biggest bestsellers of the century. In the preface to the Hebrew edition (special for "Davar" subscribers!) D. Zakai wrote: "Verse by verse from a biblical story and next to it the word of archeology that upholds its truth, and things that seemed obscure and puzzling become clear and interpreted."

Zeev Herzog, an archaeologist from Tel Aviv University, set himself the opposite goal in his article "The Bible, History and Archeology" published in the "Haaretz" supplement on 29.10.1999 to bring to public awareness the "gap between expectations for proving the Bible as a historical source and The facts revealed in the field". The diligent journalist added a sensational headline on the front page

His own - "The biblical period did not exist" - and other sub-titles in this spirit.

Herzog probably did not anticipate the tremendous public response that his words would provoke, following which dozens of angry or congratulatory reaction letters were sent to Haaretz.

Many in the scientific community raised an eyebrow at reading the sensational headlines, but in the end, they gained more public attention than dozens of books and articles published every year in scientific journals. On the wave of the public storm, about a dozen scientific gatherings were held, full of people, in which archaeologists, historians and biblical scholars presented in a concise and comprehensible manner the main points of their perception of the "historical truth in the Bible". The editors and research institutions did an important service to the interested audience by collecting and publishing sixteen of the lectures given at these meetings.

As the editors point out, "the reader looking for easy solutions and a paved way to understanding the Bible, the archaeological find and the connection between them will not find what he is looking for... and he may find himself in a dilemma in view of the multitude of mutually contradictory opinions..." (p. 2). Therefore, this list will not follow the conventional path of book reviews, and will not review one by one the articles in the file, in conflict with one opinion or another. I believe that the reader will come away more rewarded from a short guided tour of the labyrinths of scientific polemics, in the illumination of the conceptual background from which this or that opinion is derived, and the highlighting of the "burning" questions that preoccupy archaeological-historical research these days.

Naturally, the review will strive to be as simple and clear as possible (perhaps even too simplistic and schematic for the taste of experts), since its goal is similar to that which Herzog aspired to in his article from two years ago - to bring the reader closer to the essence of this important subject and invite them to further study through the file and other semi-popular literature .

As the source of the book will prove, the purely scientific discussion is not without emotional involvement and polemic, which is also expressed in labels of the type "fundamentalist", "new archaeologist", "nihilist", "denier of the Bible", "post-Zionist" and so on. As for myself, I will refrain from "giving marks" to the opinions presented in the file, and instead I will try to summarize, sort and characterize them (with references to pages) as much as possible within this narrow canvas. If I use terms such as "conservative", "skeptic" etc., they are not a value judgment, but a relative position in the sheet of opinions.

on dubious conventions

I will therefore begin with some basic comments about opinions rooted in the general consciousness, which appear here and there also in the file before us:

1. Many in the public (as I am also aware from conversations with beginning students) believe that the Bible and archeology stand on two sides of a fence, in terms of the keepers of Israel's beliefs versus those who seek progress and objective truth. Knowledge of biblical criticism is vague, if any, and so is awareness that the lines cross within the disciplines. There are "conservatives" and "skeptics" in archaeological research just as there are in biblical research, and that is not how the quality of researchers is measured. Unfortunately, the education system that transmits this simplistic dichotomy between the Bible and archeology does both of them an injustice, and the administrative separation in universities also does not contribute to bringing the two disciplines closer together. The distinction also does not necessarily depend on the worldview of those involved, and there are religious and secular researchers on both sides of the imaginary barrier. The only real barrier I know is against those who are not at all interested in either biblical studies or archeology, and they fight both with all their might.

2. A widespread belief in the public (and sometimes archaeologists also like to foster) is that archeology, unlike written sources, provides an objective picture, in terms of photographing a real situation at a given moment (by the way, a photograph can also be framed in different ways that create different effects). If that was the case, then there would not have been bitter arguments between archaeologists about the interpretation of various finds. Admittedly, the inanimate remains do not lie, but the archaeologists who speak for them are as subjective as the researchers of the texts, or in general, all those involved in the human sciences. Archeology does not have the status of "super judge" in the polemic about biblical history, but is an active partner in the cauldron.

3. Many justify their skepticism about the historical value of the Bible by the fact that it is biased, ethnocentric and completely mobilized for the theological doctrine of the "Monotheistic Manifesto". If so, we must disqualify the majority of the sources written in the ancient Near East as evidence, since they are also biased, ethnocentric and were written in praise of national gods - the Egyptian Amon, the Babylonian Marduk, the Assyrian Assyrian, the Hittite Tarthuna, the Aramaic Hadad, the Moabite Misha, etc. And what is the value of historiographical writings written in the name of Christianity, Islam or Communism? In general, in the study of postmodernist interpretation (hermeneutics), they long ago came to the conclusion that there is no objective text that is free from the ideology of its author (Yaphat, 87), and many would put the "historical truth" in the title of the book in question between quotation marks. I am not one of those who disbelieve in the very aspiration to reach the truth, and in my eyes there are narratives that are closer to the historical truth than their competitors. In any case, there is no reason to be especially strict in the standards by which the biblical sources are examined compared to other trending sources (Ben-Tor, 18).

4. Another common claim regarding the special limitations of biblical historiography is the fact that until the end of the tenth century BC (the campaign of Shishak) we have no external sources corresponding to specific events described in the Bible. Far-fetched people even try to write the history of the country between the twelfth century BC (Egypt's withdrawal from Canaan) and the ninth century BC (the divided kingdom) based only on the archaeological data and the very meager external sources. If the writing of history were to rely only on events for which we have cross-referenced sources, the pages would dwindle greatly, and "unsupported" historical sources (such as Marco Polo's travels) would go down the drain.

Even cross-referencing sources is not a guarantee of the accuracy of the historical reconstruction, as recent incidents will testify. Just as a judge must sometimes rule on his judgment only based on his impression of the accused's testimony, so too is the historian's test in his judgment to determine the plausibility according to the internal logic of the scripture itself (Hoffman, 31 Yaft, 86). But fortunately, the historian is not obliged to decide decisively whether this "was or was not", but his conclusions are spread over a wide canvas of shades of plausibility - "probably", "probably", "possible", "unacceptable". Absolute answers are quite rare in the study of the ancient world. At the same time, it seems that sometimes excessive use is made of the claim that "lack of evidence is not evidence of lack". It is true that we do not have, nor will we ever have, all the information on any affair, and any reconstruction is correct at the time. Still, the accumulated scope of the information has great weight, and it is impossible to excuse the whole herd by the coincidence of the find (Ben-Nun, 3). This is especially true of the archaeological picture in the Land of Israel, which has been excavated more than anywhere else in the world (except maybe Greece). For example: if to this day not a single Israeli royal tombstone has been discovered, such as those placed by the kings of the great kingdoms, and even lesser kings, such as Chemosh the king of Moab or Hazael the king of Aram-Damascus, this says Darshani.

Conservatism and skepticism in biblical criticism

And now to the matter itself. As mentioned, the tendency of the Bible or the fact that it is a single source for most of the periods described in it do not disqualify it in advance as a historical testimony, but to these two limitations there is a third, decisive one: the great distance of time that passed between the events described and the recording of their memory. By the way, this is also not a unique phenomenon in the literature of the world in general and in the literature of the ancient East in particular: for example, the poetry of Homer or the Hellenistic compositions of Menton on the history of Egypt, of Brussus on the history of Babylon, and of Philo Magabat on the history of Phoenicia.

Before we begin the discussion on biblical criticism, it is appropriate that we mention the many studies that have been done on the capabilities and limitations of collective memory among illiterate peoples and tribes in the world. It is very difficult to evaluate traditions passed down orally from generation to generation, but it is important to remember this dimension in any discussion of the biblical tradition (Zakovitz, 66 ff.).

Long before the flourishing of modern biblical criticism in Germany at the end of the nineteenth century (and Hausen), various commentators doubted the correctness of the tradition according to which Moses wrote the books of the Torah. Baruch Spinoza (perhaps the first "minimalist") believed as early as 1670 that the biblical historiography, beginning with the Torah and ending with the Book of Kings, was compiled by the hand of Ezra the writer based on earlier sources. The majority of biblical scholars today accept the "sources method" in one of its many versions, a method that holds that the historical books of the Bible combine different sources, which were compiled at different times and by different circles in the days of the First Temple and after, and went through several edits until the Bible was signed (RA Friedman , Who wrote the Bible? Dvir publishing house 1995). Opinions differ regarding the time each source was compiled, the scope of the earlier layers in the later complex, and their value in reconstructing the history of Israel.

However, there are quite a few researchers who stand outside the general consensus on biblical criticism and attack it from two opposite directions. At one end are those (so-called "fundamentalists") who accept the historical progression described in the Bible as written and tongue-in-cheek and are willing to accept external evidence only if it does not contradict the biblical story (Ben-Nun). At the other extreme are researchers (called "minimalists" or "nihilists") who claim that all biblical historiography is nothing but late fiction, written in the Persian period and the beginning of the Hellenistic period (fifth-third centuries BC). This view, which is shared by several researchers in Europe, mainly from England and Denmark (the "Copenhagen school"), has far-reaching consequences regarding the very belonging of the people of Israel to their country in antiquity, and it is possible to attribute to some of its followers (but not all) anti-Zionist political motives (see Hoffman, 26 onwards).

Naturally, this approach is not represented in the file, but it echoes from the fierce polemic against it in many of the articles. Even before this absurd theory is put on the pedestal of historical logic, it collapses in a simple linguistic test (see Horvitz). There is a clear distinction between the past and

The classical of the days of the First Temple and the later Hebrew, the saturation of "neologisms" and Aramaic influences, of the days of the Second Temple, in which the later books (Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah and the Chronicles) were written. For example, a "letter" would be a "book" in classical Hebrew, an "epistle" in late Hebrew. The distinction between the layers of the language is also confirmed in the set of Hebrew inscriptions discovered in excavations in Israel, and it is surprising that those with the "nihilistic" approach ignore this important data.

As mentioned, most biblical scholars, archaeologists and historians in Israel and around the world stand somewhere in the middle of the road (as most of the writers in the collection attest to themselves), and believe that the historical books in the Bible were assembled and processed into a comprehensive historiographical work on the history of the nation at the end of the Kingdom of Judah (seventh century BC), As part of the religious reforms of King Josiah, and this composition ("The Deuteronomistic History") was completed and underwent further editing in the Babylonian exile (sixth century BC) and after the return to Zion (fifth century BC). However, the researchers are fundamentally divided on the question of what is the relative weight of the ancient sources that stood before the eyes of the later authors, and above all, what is their degree of historical reliability. The main source of information from which the later author drew his knowledge is probably found in the temple and palace library in Jerusalem, where various administrative documents (border descriptions, lists of cities, tax lists), stories of conquest and heroism, ancient poetry fragments (the song of Deborah), and royal chronicles were accumulated over the generations to which he refers The Bible itself, such as "The Book of Solomon", and the books of the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah and the Kings of Israel. Naturally, the Jewish author knew the history of his kingdom better, but he also had quite a few Israeli sources before him, mainly from the stories of the prophets, who were revealed to Judah and thus were saved from destruction (Kogan, 95). It is possible that the "editing table" of the author also reached non-Israelite local traditions (Mazar, 109), for example, from the cities of the Philistine and Phoenician kingdoms. Of course, as he got closer to his time, the author relied more and more on his personal knowledge and that of his contemporaries.

Although there is no dispute that biblical historiography was not created in a vacuum of sources, doubts arise about the degree of reliability of these sources, even after peeling off the literary and propagandistic cover. Also, it must be assumed that many gaps remained in the chain of events even after the collection of the written sources and oral traditions, and these gaps were filled by the author or the editor according to his best imagination. Therefore, in the eyes of "skeptical" scholars (Herzog, Zakovitz, Na'eman, Finkelstein), the "ancient seeds" embedded in biblical historiography are (almost) worthless in reconstructing their stated period because it was unrecognizably distorted by the later writers. In the eyes of Zakovitz, for example (71), "the biblical story is no different in its factual reliability from the modern historical novel", for example, "Ivanhoe" by Walter Scott.

Despite this uncompromising verdict, even the "skeptical" historians find great benefit in the later writings as reflecting the period in which they were written. This is essentially the message of the postmodernist interpretation of the text, whose application in ancient philology was developed mainly by the Italian historian M. Livrani and researchers who followed him. To summarize his teaching in one sentence: it is not important what is written, but who wrote it and for what purpose. No longer a fruitless search for the "historical core", but identifying the "fingerprints" of the writer and reconstructing his social and political being. If the conquests of Joshua and David are worthless for their stated period, they contain much information as a reflection of the days of Josiah, returning the crown to its former glory, who annexed the territory of the Kingdom of Israel to the Kingdom of Judah following the withdrawal of the Assyrians from the land (Na'amen, 126 Finkelstein, 151

More "conservative" researchers (Ben-Tor, Hoffman, Zertal, Yafet, Kogan, Mazar, Melmet, Kalai) treat the ancient traditions with more trust, and in principle, they accept the biblical testimony as long as the contrary is not proven. To justify their position, they point, among other things, to the relatively good correspondence between the biblical descriptions and external sources from the time of the events, such as the Egyptian Shishak expedition or the slavery of Misha the Moabite (Kogan, 93; Mazar, 108); on various items in the story of the construction of the temple in the days of Solomon (Horwitz, 49); On the map of the tribal estates as reflecting the days of the United Kingdom (Klai, 160), etc. It is possible that there are even entire narrative divisions that are historically reliable, since otherwise it is difficult to explain why a historian from the time of Josiah Lashevtz found it necessary to include in his composition the extensive and detailed apologetics about the circumstances of the rise to power of the House of David while eradicating the House of Saul (Hoffman, 31). Most scholars refer to the biblical text as appropriate for historical study, although locating the ancient and reliable sunsets within the later complex is a difficult and complex task. This is similar to the situation of a buyer in an antique store where only a small part of the items offered for sale are authentic and the correct identification of these valuable items depends on the skill of the buyer (and in this example there is no reason to recommend, God forbid, the purchase of antiques).

Archeology and biblical history

In the third part of the list, I will briefly briefly review the research status of "biblical archaeology" in relation to the main periods in Israel's history according to the biblical sequence. Of course, I will not be able to comment on the abundance of information and opinions presented in the file, but I will direct the spotlight to the issues that are at the forefront of the discussion. It is possible to compare the criticism of biblical archeology to dominoes standing in a "chronological column"; A cube that fails the test of history threatens the one after it, and every researcher stops the "domino effect" in a place that seems stable and existing.

The period of the ancestors has almost disappeared from the archaeological discourse as a period with historical reality, although some are trying to breathe life into it (Ben-Nun, 3). The stories of the ancestors are no longer anchored in the beginning of the second millennium in accordance with the biblical chronology (as Albright and his students believed), but the debate continues as to which reality is reflected in them - that of the end of the period of the judges and the beginning of the monarchy (as Benjamin Mazar believed), or that of the end of the period of the monarchy (Finkelstein, 149 ). At the same time, there are some glosses in these stories that have an "antique flavor", such as the names of the fathers and mothers, which no longer appear in the royal period, or the names of the kings of the north in Genesis, which also have parallels in the second millennium (for example, "Tadal", as the name of several kings het).

The stay in Egypt and the exodus from Egypt have recently been re-discussed, while examining the general historical background of the traditions (Hoffman, Mazar, 30; Melmet, 98, 113). Admittedly, no archaeological confirmation has been found for the Israelites' journeys in the desert (Herzog, 56), but the historical reality of the new Egyptian kingdom more or less corresponds to what is told in the Bible about groups of nomadic shepherds who came down in the years camping in the eastern delta region to break hunger. The biblical "City of Ramses" is without a doubt identified with P(r)-Ramses, the capital of Ramses II at its eastern entrance, and this city sank into the abyss of femininity after the twelfth century BC. In 1208 BC, the name "Israel" is encountered for the first time in a stele describing a military expedition to the land of Canaan by his son Maranphet, and this is an Archimedean point in any discussion of the beginnings of Israel's history. Therefore, quite a few researchers believe that the traditions about Egypt preserve some historical memory from the second millennium BC, including the migration of groups of exiles to Canaan and their integration into the rest of the country's population. In this context it is also necessary to mention some Egyptian names among the religious leadership, such as Phinehas the grandson of Aaron the priest, and of course, also Moses himself, whose name is apparently based on the same Egyptian verb ("to beget") that also appears in the names of the pharaohs of Egypt (Thutmes, Ramses ).

The settlement period received the main research boost in the last generation thanks to the archaeological surveys conducted in the central mountain after 1967. In its general outlines the picture is quite clear, although there are fierce debates about its details (Zertal, 76). From the end of the thirteenth century to the eleventh century, there were large-scale waves of settlement in Samaria (mainly in the Menashe region), and with reduced intensity in Judea and the Galilee. Whether one identifies these settlers as Israelis (Ben-Tor, Zertal, Mazar, Simon), or whether, for the sake of caution, they are called "proto-Israelis" (Finkelstein), there is no doubt that these are precisely the areas where the Israeli national entity grew, and perhaps this led to Also Marnfath's journey against "Israel" in 1208 BC. There is no consensus on the origin of the new settlers; Were they immigrants from distant lands (as told in the Bible), refugees from the nearby Canaanite settlements (Mendenhall), nomads from the Transjordan desert (Zartel), local nomads (Finkelstein), or a combination of all these (Naman). Also regarding the possibility of finding close parallels between the biblical story and the archaeological settlement process, opinions are fundamentally divided. Few still rely on the stories of the uniform and rapid conquest by the twelve tribes under the leadership of Yehoshua, but on the other hand, many find archaeological confirmation of traditions about a gradual entry and slow settlement in the land, as well as about the conquest of Hazor (Ben-Nun, Ben-Tor, Zertal, Mazar). In contrast, the "skeptics" find glaring contradictions between the biblical description and the archaeological data (Naaman, Finkelstein). Recently, the polemic surrounding the questions of the settlement has quieted down somewhat, and the front of the discussion has shifted to the parallel settlement of the Philistines, and especially to the growth of the monarchy in Israel and Judea.

The United Kingdom (150th century BC) has moved in the last decade to the focus of the archaeological-historical polemic. This is the last "swinging" cube in the "domino effect" of Israel's history, on which "fierce battles" are written in scientific meetings and on the pages of the professional press. The erosion of the position of the United Kingdom as the beginning of the distinct historical era in the history of Israel (as opposed to the proto/prehistoric era before it; see Melmet) began with the works of several "minimalist" biblical scholars in the world in the eighties and nineties, who questioned the biblical description of the kingdom of David and Solomon as a period of glory, Unprecedented unity and political power. In their wake, several Israeli archaeologists, mainly from Tel Aviv University (Osishkin, Herzog, Finkelstein), examined the archaeological data and came to similar conclusions: the remains that are definitely dated to the tenth century lack the main characteristics of a "mature" state, such as a developed urban society, monumental construction, Luxury products, and above all, extensive use in writing for administrative purposes. Particularly noticeable is the lack of these state markers in Jerusalem, the capital of David's kingdom, which was flooded "with all the kings beyond the river" (Malachi XNUMX:XNUMX). During XNUMX years of archaeological research, not even in the City of David, but a handful of findings from the tenth century were discovered. Following the Land of Judah, the layers of the "United Kingdom" in the north of the country were also re-examined, and here too the "Tel Avivians" discovered a similar picture: the monumental gates in Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer, which were attributed by Yigal Yedin to Solomon, they move to the days of Ahab in the ninth century AD s, and thus the ground is dropped from under the existence of a "united kingdom" (pan-Israel) before the "division" (so to speak) into two kingdoms.

The "Jerusalemites" fight back and claim that the revision of the views of the "Tel Avivites" in the 25s is nothing but the adoption of the deconstructive times of the European "minimalists" and the unnecessary slaughter of "sacred cows" (Ben-Tor; 100 Mazar, 21). They claim that the disputed layers should only be dated according to the ceramic find, and not according to theoretical sociological models. They also point to the paradox that even the "new" archaeologists, who seek to free themselves from dependence on the Bible, ultimately rely on the biblical evidence for the time of the construction of the royal complex in Israel during the days of Ahab (Ben-Tor, 101 Mazar, 108). As far as Jerusalem is concerned, it is true that there are not many remains of the United Kingdom, but the massive retaining wall built in the City of David in the twelfth century BC continued to be used even in David's time (Mazar, XNUMX). It should also be taken into account that the magnificent buildings of government and religion built by Solomon according to the Bible were in the Temple Mount complex and will never be discovered. In conclusion, even if the United Kingdom's glory as the idyllic "Golden Age" has been forgotten, its importance as the formative period of the Israeli monarchy remains the same and there is no rush to erase it from the history books.

In miraculous timing, in 1993 an Aramaic inscription from the middle of the ninth century BC was discovered in Tel Dan mentioning the "House of David". This important discovery indeed confirms (for those who doubted it) the history of David's character (even though there were attempts to find different and different alternative explanations), but it does not resolve the questions concerning the nature and extent of his kingdom, and the polemic will probably continue for a long time.

The kingdoms of Israel and Judah are also affected by the "shocks" that afflict the United Kingdom, although the controversy surrounding them is less heated. Those who dispute the existence of the united Kingdom of Israel in the tenth century must point to the time and circumstances of the growth of the two separate Israeli kingdoms. Examining the archaeological data according to the standards of comparative socio-political research led Finkelstein (following Jamieson-Drake) to the conclusion that the conditions for the development of a developed state matured only in the ninth century BC in the Northern Kingdom (Beit Omri), while Judah did not develop at all A real country before the destruction of Israel at the end of the eighth century BC (152, 147). Regarding the historical succession in the two Israeli kingdoms, we also have at our disposal for the first time occasional extra-biblical evidence - Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Aramaic (the inscription from Dan) and Moabite (the inscription from Misha), as well as a growing corpus of Hebrew inscriptions from the Land of Israel, such as Samaria pottery, Arad inscriptions , letters from Lachish, and more recently, the seals from Jerusalem that belonged to well-known figures from the end of the First Temple, including "Barchihu ben Neriah the scribe", the personal secretary of Jeremiah the prophet. Admittedly, these external sources only form a thin fabric, but they generally support the historical skeleton in the Bible.

From an archaeological revolution and post-Zionism?

Few of the writers in the collection refer to the growth of Israeli monotheism (Herzog, 61 and compare Kalai, 161), and indeed, it is appropriate that this complex issue be brought to the general public separately. Another issue that comes up in some of the articles is what Herzog calls the "scientific revolution", that is, the accelerated transition from "biblical archaeology" to "social archaeology" (Herzog, 61 ff.). This development has many positive aspects, but also less happy aspects. There is no disputing the importance of new research methods harnessing the technologies of the natural sciences, and this is also true for expanding the archaeological-historical discussion to economic, social and ecological issues.

On the other hand, less exciting is "the disconnection of archeology from the shackles of the Bible" (Herzog, 62) and the written sources in general. It goes without saying that "both fields of research must develop their research independently and independently, and only then check the mutual significance of their findings" (ibid.), but who exactly is supposed to check this mutual significance and when? There is no supreme authority that is outside the cauldron of debate, and the synthesis is created gradually from a continuous dialogue between the disciplines and not somewhere at the end of days when each discipline will "solve its problems" separately.

Unfortunately, the turning of the rear to biblical archeology and history in general is to a large extent responsible for the fact that the number of young students and researchers who combine archeology, the Bible and history in their studies and research is decreasing (and perhaps this is also evidenced by the fact that all the writers in the collection, who are young at heart, are fifty years old or older). I am afraid that if there is no fundamental change in the approach of the research institutions, in the next generation the number of seminars and publications such as the one represented in the file will decrease greatly. I wish you were lost.

Many of the writers refer directly or indirectly to the connection of the controversy over biblical history to the questions of Israeli national identity today. I agree with the striking words of A. Mazar (97), which probably express the opinion of most of the writers in the collection: "The power of these events is actually their presence in the scriptures and their acceptance by the entire nation as a common heritage. The question of the degree of historical reliability of the sources of the Bible must therefore be seen as a purely research issue, which does not carry an ideological charge". I will not elaborate on this interesting issue, which also occupied a central place in the many response letters published following Herzog's article.

Nevertheless, it is impossible not to comment briefly on Uriel Simon's (surprising) article under the title "Post-biblical and post-Zionist archaeology", in which he makes an equal distinction between the "subversive archaeological findings" (137) presented by Herzog and researchers who share his opinion and between positions "Post-Zionism". A typical sentence summarizing his words: "Zionist archeology sought to reveal our roots in the land in order to deepen our grip on it, while post-Zionist archeology seeks to cut roots so that we can take off without hindrance" (ibid.). take off where? There is in this a dishonorable and even dangerous impeachment of the hidden motives of serious researchers whose Zionist commitment does not need qualification from anyone. Woe to us if researchers in Israeli research institutions subject their scientific integrity to the ideological image that their conclusions may create in the eyes of the keepers of the "Zionist foundations". My dispute with Herzog and other followers of severing archeology from the shackles of the Bible is disciplinary-epistemological, and has nothing to do with "post-Zionist" views and contemporary political positions. Like Herzog, my national consciousness is not conditioned by the historical truth of the exodus from Egypt or the dimensions of David's kingdom.

I admit that exposing a contradiction between the Bible and archeology does not pain me as much as it pains Simon (136), and to the same extent, exposing a compatibility between the two does not fill me with either happiness or sadness. I try to avoid "hostile interpretation" or "sympathetic interpretation" (138), which inevitably lead to squaring the circle. Only the feeling that I did my job faithfully and reached defensible results gives me professional satisfaction. As for my national pride, it is based on the fact that the central ethos in the story of the Exodus is the idea of universal freedom (and not necessarily heroism, as in many national ethos), that the "trial of the king" in 3000 Samuel XNUMX is the first manifesto against tyrannical tyranny (thousands of years before the French Revolution ), and that the prophets of Israel preached the teachings of morality and justice without fearing images in the eyes of the establishment or public opinion. What's more: these lines are written in the same language that was spoken in the streets of Jerusalem XNUMX years ago, and it doesn't matter to me if it was the capital of an empire or a small mountain fortress.

The writer is a professor in the Department of Archeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations

at Tel Aviv University.

This title, but without the question mark, is borrowed from the Hebrew translation of a book published in Germany in the 1955s under the title "And yet the Bible is right" (originally 1958 Werner Keller, The Bible as History, published by Hebraut Seferat XNUMX). It was a fairly routine review of archaeological discoveries from the ancient Near East that support the biblical story, a book that many like it were written before and after. However, the provocative title and the easy-to-understand style of writing made the book, which was translated into dozens of languages, one of the biggest bestsellers of the century. In the preface to the Hebrew edition (special for "Davar" subscribers!) D. Zakai wrote: "Verse by verse from a biblical story and next to it the word of archeology that upholds its truth, and things that seemed obscure and puzzling become clear and interpreted."

Zeev Herzog, an archaeologist from Tel Aviv University, set himself the opposite goal in his article "The Bible, History and Archeology" published in the "Haaretz" supplement on 29.10.1999 to bring to public awareness the "gap between expectations for proving the Bible as a historical source and The facts revealed in the field". the journalist

http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/images/printed/P211201/t.0.2112.400.2.7.jpg

lanruoJ noitarolpxE

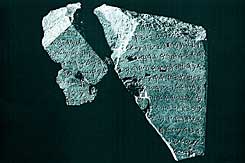

An Aramaic inscription from Tel Dan containing the first non-biblical mention of the "House of David"

The hard worker added his own sensational headline on the first page - "The biblical period did not exist" - and other sub-headings in this vein. Herzog probably did not anticipate the tremendous public response that his words would provoke, following which dozens of angry or congratulatory reaction letters were sent to Haaretz. Many in the scientific community raised an eyebrow at reading the sensational headlines, but in the end, they gained more public attention than dozens of books and articles published every year in scientific journals. On the wave of the public storm, about a dozen scientific gatherings were held, full of people, in which archaeologists, historians and biblical scholars presented in a concise and comprehensible manner the main points of their perception of the "historical truth in the Bible". The editors and research institutions did an important service to the interested audience by collecting and publishing sixteen of the lectures given at these meetings.

As the editors point out, "the reader looking for easy solutions and a paved way to understanding the Bible, the archaeological find and the connection between them will not find what he is looking for... and he may find himself in a dilemma in view of the multitude of mutually contradictory opinions..." (p. 2). Therefore, this list will not follow the conventional path of book reviews, and will not review one by one the articles in the file, in conflict with one opinion or another. I believe that the reader will come away more rewarded from a short guided tour of the labyrinths of scientific polemics, in the illumination of the conceptual background from which this or that opinion is derived, and the highlighting of the "burning" questions that preoccupy archaeological-historical research these days. Naturally, the review will strive to be as simple and clear as possible (perhaps even too simplistic and schematic for the taste of experts), since its goal is similar to that which Herzog aspired to in his article from two years ago - to bring the reader closer to the essence of this important subject and invite them to further study through the file and other semi-popular literature .

As the source of the book will prove, the purely scientific discussion is not without emotional involvement and polemic, which is also expressed in labels of the type "fundamentalist", "new archaeologist", "nihilist", "denier of the Bible", "post-Zionist" and so on. As for myself, I will refrain from "giving marks" to the opinions presented in the file, and instead I will try to summarize, sort and characterize them (with references to pages) as much as possible within this narrow canvas. If I use terms such as "conservative", "skeptic" etc., they are not a value judgment, but a relative position in the sheet of opinions.

on dubious conventions

I will therefore begin with some basic comments about opinions rooted in the general consciousness, which appear here and there also in the file before us:

1. Many in the public (as I am also aware from conversations with beginning students) believe that the Bible and archeology stand on two sides of a fence, in terms of the keepers of Israel's beliefs versus those who seek progress and objective truth. Knowledge of biblical criticism is vague, if any, and so is awareness that the lines cross within the disciplines. There are "conservatives" and "skeptics" in archaeological research just as there are in biblical research, and that is not how the quality of researchers is measured. Unfortunately, the education system that transmits this simplistic dichotomy between the Bible and archeology does both of them an injustice, and the administrative separation in universities also does not contribute to bringing the two disciplines closer together. The distinction also does not necessarily depend on the worldview of those involved, and there are religious and secular researchers on both sides of the imaginary barrier. The only real barrier I know is against those who are not at all interested in either biblical studies or archeology, and they fight both with all their might.

2. A common belief in the public (and sometimes archaeologists also like to foster) is that archeology, unlike written sources, provides an objective picture, in terms of photographing a real situation at a given moment (by the way, a photograph can also be framed in different ways that create different effects). If that was the case, then there would not have been bitter arguments between archaeologists about the interpretation of various finds. Admittedly, the inanimate remains do not lie, but the archaeologists who speak for them are as subjective as the researchers of the texts, or in general, all those involved in the human sciences. Archeology does not have the status of "super judge" in the polemic about biblical history, but is an active partner in the cauldron.

3. Many justify their skepticism about the historical value of the Bible by the fact that it is biased, ethnocentric and completely mobilized for the theological doctrine of the "monotheistic manifesto". If so, we must disqualify the majority of the sources written in the ancient Near East as evidence, since they are also biased, ethnocentric and were written in praise of national gods - the Egyptian Amon, the Babylonian Marduk, the Assyrian Assyrian, the Hittite Tarthuna, the Aramaic Hadad, the Moabite Misha, etc. And what is the value of historiographical writings written in the name of Christianity, Islam or Communism? In general, in the study of postmodernist interpretation (hermeneutics), they long ago came to the conclusion that there is no objective text that is free from the ideology of its author (Yaphat, 87), and many would put the "historical truth" in the title of the book in question between quotation marks. I am not one of those who disbelieve in the very aspiration to reach the truth, and in my eyes there are narratives that are closer to the historical truth than their competitors. In any case, there is no reason to be especially strict in the standards by which the biblical sources are examined compared to other trending sources (Ben-Tor, 18).

4. Another common claim regarding the special limitations of biblical historiography is the fact that until the end of the tenth century BC (the campaign of Shishak) we have no external sources corresponding to specific events described in the Bible. Far-fetched people even try to write the history of the country between the twelfth century BC (Egypt's withdrawal from Canaan) and the ninth century BC (the divided kingdom) based only on the archaeological data and the very meager external sources. If the writing of history were to rely only on events for which we have cross-referenced sources, the pages would dwindle greatly, and "unsupported" historical sources (such as Marco Polo's travels) would go down the drain.

Even cross-referencing sources is not a guarantee of the accuracy of the historical reconstruction, as recent incidents will testify. Just as a judge must sometimes rule on his judgment only based on his impression of the accused's testimony, so too is the historian's test in his judgment to determine the plausibility according to the internal logic of the scripture itself (Hoffman, 31 Yaft, 86). But fortunately, the historian is not obliged to decide decisively whether this "was or was not", but his conclusions are spread over a wide canvas of shades of plausibility - "probably", "probably", "possible", "unacceptable". Absolute answers are quite rare in the study of the ancient world. At the same time, it seems that sometimes excessive use is made of the claim that "lack of evidence is not evidence of lack". It is true that we do not have, nor will we ever have, all the information on any affair, and any reconstruction is correct at the time. Still, the accumulated scope of the information has great weight, and it is impossible to excuse the whole herd by the coincidence of the find (Ben-Nun, 3). This is especially true of the archaeological picture in the Land of Israel, which has been excavated more than anywhere else in the world (except maybe Greece). For example: if to this day not a single Israeli royal tombstone has been discovered, such as those placed by the kings of the great kingdoms, and even lesser kings, such as Chemosh the king of Moab or Hazael the king of Aram-Damascus, this says Darshani.

Conservatism and skepticism in biblical criticism

And now to the matter itself. As mentioned, the tendency of the Bible or the fact that it is a single source for most of the periods described in it do not disqualify it in advance as a historical testimony, but to these two limitations there is a third, decisive one: the great distance of time that passed between the events described and the recording of their memory. By the way, this is also not a unique phenomenon in the literature of the world in general and in the literature of the ancient East in particular: for example, the poetry of Homer or the Hellenistic compositions of Menton on the history of Egypt, of Brussus on the history of Babylon, and of Philo Magabat on the history of Phoenicia.

Before we begin the discussion on biblical criticism, it is appropriate that we mention the many studies that have been done on the capabilities and limitations of collective memory among illiterate peoples and tribes in the world. It is very difficult to evaluate traditions passed down orally from generation to generation, but it is important to remember this dimension in any discussion of the biblical tradition (Zakovitz, 66 ff.).

Long before the flourishing of modern biblical criticism in Germany at the end of the nineteenth century (and Hausen), various commentators doubted the correctness of the tradition according to which Moses wrote the books of the Torah. Baruch Spinoza (perhaps the first "minimalist") believed as early as 1670 that the biblical historiography, beginning with the Torah and ending with the Book of Kings, was compiled by the hand of Ezra the writer based on earlier sources. The majority of biblical scholars today accept the "sources method" in one of its many versions, a method that holds that the historical books of the Bible combine different sources, which were compiled at different times and by different circles in the days of the First Temple and after, and went through several edits until the Bible was signed (RA Friedman , Who wrote the Bible? Dvir publishing house 1995). Opinions differ regarding the time each source was compiled, the scope of the earlier layers in the later complex, and their value in reconstructing the history of Israel.

However, there are quite a few researchers who stand outside the general consensus on biblical criticism and attack it from two opposite directions. At one end are those (so-called "fundamentalists") who accept the historical progression described in the Bible as written and tongue-in-cheek and are willing to accept external evidence only if it does not contradict the biblical story (Ben-Nun). At the other extreme are researchers (called "minimalists" or "nihilists") who claim that all biblical historiography is nothing but late fiction, written in the Persian period and the beginning of the Hellenistic period (fifth-third centuries BC). This view, which is shared by several researchers in Europe, mainly from England and Denmark (the "Copenhagen school"), has far-reaching consequences regarding the very belonging of the people of Israel to their country in antiquity, and it is possible to attribute to some of its followers (but not all) anti-Zionist political motives (see Hoffman, 26 onwards).

Naturally, this approach is not represented in the file, but it echoes from the fierce polemic against it in many of the articles. Even before this absurd theory is put on the pedestal of historical logic, it collapses in a simple linguistic test (see Horvitz). There is a clear distinction between the classical Hebrew of the First Temple and the later Hebrew, saturated with "neologisms" and Aramaic influences, of the Second Temple, in which the later books (Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles) were written. For example, a "letter" would be a "book" in classical Hebrew, an "epistle" in late Hebrew. The distinction between the layers of the language is also confirmed in the set of Hebrew inscriptions discovered in excavations in Israel, and it is surprising that those with the "nihilistic" approach ignore this important data.

As mentioned, most biblical scholars, archaeologists and historians in Israel and around the world stand somewhere in the middle of the road (as most of the writers in the collection attest to themselves), and believe that the historical books in the Bible were assembled and processed into a comprehensive historiographical work on the history of the nation at the end of the Kingdom of Judah (seventh century BC), As part of the religious reforms of King Josiah, and this composition ("The Deuteronomistic History") was completed and underwent further editing in the Babylonian exile (sixth century BC) and after the return to Zion (fifth century BC). However, the researchers are fundamentally divided on the question of what is the relative weight of the ancient sources that stood before the eyes of the later authors, and above all, what is their degree of historical reliability. The main source of information from which the later author drew his knowledge is probably found in the temple and palace library in Jerusalem, where various administrative documents (border descriptions, lists of cities, tax lists), stories of conquest and heroism, ancient poetry fragments (the song of Deborah), and royal chronicles were accumulated over the generations to which he refers The Bible itself, such as "The Book of Solomon", and the books of the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah and the Kings of Israel. Naturally, the Jewish author knew the history of his kingdom better, but he also had quite a few Israeli sources before him, mainly from the stories of the prophets, who were revealed to Judah and thus were saved from destruction (Kogan, 95). It is possible that the "editing table" of the author also reached non-Israelite local traditions (Mazar, 109), for example, from the cities of the Philistine and Phoenician kingdoms. Of course, as he got closer to his time, the author relied more and more on his personal knowledge and that of his contemporaries.

Although there is no dispute that biblical historiography was not created in a vacuum of sources, doubts arise about the degree of reliability of these sources, even after peeling off the literary and propagandistic cover. Also, it must be assumed that many gaps remained in the chain of events even after the collection of the written sources and oral traditions, and these gaps were filled by the author or the editor according to his best imagination. Therefore, in the eyes of "skeptical" scholars (Herzog, Zakovitz, Na'eman, Finkelstein), the "ancient seeds" embedded in biblical historiography are (almost) worthless in reconstructing their stated period because it was unrecognizably distorted by the later writers. In the eyes of Zakovitz, for example (71), "the biblical story is no different in its factual reliability from the modern historical novel", for example, "Ivanhoe" by Walter Scott.

Despite this uncompromising verdict, even the "skeptical" historians find great benefit in the later writings as reflecting the period in which they were written. This is essentially the message of the postmodernist interpretation of the text, whose application in ancient philology was developed mainly by the Italian historian M. Livrani and researchers who followed him. To summarize his teaching in one sentence: it is not important what is written, but who wrote it and for what purpose. No longer a fruitless search for the "historical core", but identifying the "fingerprints" of the writer and reconstructing his social and political being. If the conquests of Joshua and David are worthless for their stated period, they contain a lot of information as a reflection of the days of Josiah, returning the crown to its former glory, who annexed the territory of the Kingdom of Israel to the Kingdom of Judah following the withdrawal of the Assyrians from the land (Finkelstein, 126; 151

More "conservative" researchers (Ben-Tor, Hoffman, Zertal, Yafet, Kogan, Mazar, Melmet, Kalai) treat the ancient traditions with more trust, and in principle, they accept the biblical testimony as long as the contrary is not proven. To justify their position, they point, among other things, to the relatively good correspondence between the biblical descriptions and external sources from the time of the events, such as the Egyptian Shishak expedition or the slavery of Misha the Moabite (Kogan, 93; Mazar, 108); on various items in the story of the construction of the temple in the days of Solomon (Horwitz, 49); On the map of the tribal estates as reflecting the days of the United Kingdom (Klai, 160), etc. It is possible that there are even entire narrative divisions that are historically reliable, since otherwise it is difficult to explain why a historian from the time of Josiah Lashevtz found it necessary to include in his composition the extensive and detailed apologetics about the circumstances of the rise to power of the House of David while eradicating the House of Saul (Hoffman, 31). Most scholars refer to the biblical text as appropriate for historical study, although locating the ancient and reliable sunsets within the later complex is a difficult and complex task. This is similar to the situation of a buyer in an antique store where only a small part of the items offered for sale are authentic and the correct identification of these valuable items depends on the skill of the buyer (and in this example there is no reason to recommend, God forbid, the purchase of antiques).

Archeology and biblical history

In the third part of the list, I will briefly briefly review the research status of "biblical archaeology" in relation to the main periods in Israel's history according to the biblical sequence. Of course, I will not be able to comment on the abundance of information and opinions presented in the file, but I will direct the spotlight to the issues that are at the forefront of the discussion. It is possible to compare the criticism of biblical archeology to dominoes standing in a "chronological column"; A cube that fails the test of history threatens the one after it, and every researcher stops the "domino effect" in a place that seems stable and existing.

The period of the ancestors has almost disappeared from the archaeological discourse as a period with historical reality, although some are trying to breathe life into it (Ben-Nun, 3). The stories of the ancestors are no longer anchored in the beginning of the second millennium in accordance with the biblical chronology (as Albright and his students believed), but the debate continues as to which reality is reflected in them - that of the end of the period of the judges and the beginning of the monarchy (as Benjamin Mazar believed), or that of the end of the period of the monarchy (Finkelstein, 149 ). At the same time, there are some glosses in these stories that have an "antique flavor", such as the names of the fathers and mothers, which no longer appear in the royal period, or the names of the kings of the north in Genesis, which also have parallels in the second millennium (for example, "Tadal", as the name of several kings het).

The stay in Egypt and the exodus from Egypt have recently been re-discussed, while examining the general historical background of the traditions (Hoffman, Mazar, 30; Melmet, 98, 113). Admittedly, no archaeological confirmation has been found for the Israelites' journeys in the desert (Herzog, 56), but the historical reality of the new Egyptian kingdom more or less corresponds to what is told in the Bible about groups of nomadic shepherds who came down in the years camping in the eastern delta region to break hunger. The biblical "City of Ramses" is without a doubt identified with P(r)-Ramses, the capital of Ramses II at its eastern entrance, and this city sank into the abyss of femininity after the twelfth century BC. In 1208 BC, the name "Israel" is encountered for the first time in a stele describing a military expedition to the land of Canaan by his son Maranphet, and this is an Archimedean point in any discussion of the beginnings of Israel's history. Therefore, quite a few researchers believe that the traditions about Egypt preserve some historical memory from the second millennium BC, including the migration of groups of exiles to Canaan and their integration into the rest of the country's population. In this context it is also necessary to mention some Egyptian names among the religious leadership, such as Phinehas the grandson of Aaron the priest, and of course, also Moses himself, whose name is apparently based on the same Egyptian verb ("to beget") that also appears in the names of the pharaohs of Egypt (Thutmes, Ramses ).

The settlement period received the main research boost in the last generation thanks to the archaeological surveys conducted in the central mountain after 1967. In its general outlines the picture is quite clear, although there are fierce debates about its details (Zertal, 76). From the end of the thirteenth century to the eleventh century, there were large-scale waves of settlement in Samaria (mainly in the Menashe region), and with reduced intensity in Judea and the Galilee. Whether one identifies these settlers as Israelis (Ben-Tor, Zertal, Mazar, Simon), or whether, for the sake of caution, they are called "proto-Israelis" (Finkelstein), there is no doubt that these are precisely the areas where the Israeli national entity grew, and perhaps this led to Also Marnfath's journey against "Israel" in 1208 BC. There is no consensus on the origin of the new settlers; Were they immigrants from distant lands (as told in the Bible), refugees from the nearby Canaanite settlements (Mendenhall), nomads from the Transjordan desert (Zartel), local nomads (Finkelstein), or a combination of all these (Naman). Also regarding the possibility of finding close parallels between the biblical story and the archaeological settlement process, opinions are fundamentally divided. Few still rely on the stories of the uniform and rapid conquest by the twelve tribes under the leadership of Yehoshua, but on the other hand, many find archaeological confirmation of traditions about a gradual entry and slow settlement in the land, as well as about the conquest of Hazor (Ben-Nun, Ben-Tor, Zertal, Mazar). In contrast, the "skeptics" find glaring contradictions between the biblical description and the archaeological data (Naaman, Finkelstein). Recently, the polemic surrounding the questions of the settlement has quieted down somewhat, and the front of the discussion has shifted to the parallel settlement of the Philistines, and especially to the growth of the monarchy in Israel and Judea.

The United Kingdom (150th century BC) has moved in the last decade to the focus of the archaeological-historical polemic. This is the last "swinging" cube in the "domino effect" of Israel's history, on which "fierce battles" are written in scientific meetings and on the pages of the professional press. The erosion of the position of the United Kingdom as the beginning of the distinct historical era in the history of Israel (as opposed to the proto/prehistoric era before it; see below) began with the works of several "minimalist" biblical scholars in the world in the eighties and nineties, who questioned the biblical description of the kingdom of David and Solomon as a period of glory, Unprecedented unity and political power. In their wake, several Israeli archaeologists, mainly from Tel Aviv University (Osishkin, Herzog, Finkelstein), examined the archaeological data and came to similar conclusions: the remains that are definitely dated to the tenth century lack the main characteristics of a "mature" state, such as a developed urban society, monumental construction, Luxury products, and above all, extensive use in writing for administrative purposes. Particularly noticeable is the lack of these state markers in Jerusalem, the capital of David's kingdom, which was flooded "with all the kings beyond the river" (Malachi XNUMX:XNUMX). During XNUMX years of archaeological research, not even in the City of David, but a handful of findings from the tenth century were discovered. Following the Land of Judah, the layers of the "United Kingdom" in the north of the country were also re-examined, and here too the "Tel Avivians" discovered a similar picture: the monumental gates in Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer, which were attributed by Yigal Yedin to Solomon, they move to the days of Ahab in the ninth century AD s, and thus the ground is dropped from under the existence of a "united kingdom" (pan-Israel) before the "division" (so to speak) into two kingdoms.

The "Jerusalemites" fight back and claim that the revision of the views of the "Tel Avivites" in the 25s is nothing but the adoption of the deconstructive times of the European "minimalists" and the unnecessary slaughter of "sacred cows" (Ben-Tor; 100 Mazar, 21). They claim that the disputed layers should only be dated according to the ceramic find, and not according to theoretical sociological models. They also point to the paradox that even the "new" archaeologists, who seek to free themselves from dependence on the Bible, ultimately rely on the biblical evidence for the time of the construction of the royal complex in Israel during the days of Ahab (Ben-Tor, 101 Mazar, 108). As far as Jerusalem is concerned, it is true that there are not many remains of the United Kingdom, but the massive retaining wall built in the City of David in the twelfth century BC continued to be used even in David's time (Mazar, XNUMX). It should also be taken into account that the magnificent buildings of government and religion built by Solomon according to the Bible were in the Temple Mount complex and will never be discovered. In conclusion, even if the United Kingdom's glory as the idyllic "Golden Age" has been forgotten, its importance as the formative period of the Israeli monarchy remains the same and there is no rush to erase it from the history books.

In miraculous timing, in 1993 an Aramaic inscription from the middle of the ninth century BC was discovered in Tel Dan mentioning the "House of David". This important discovery indeed confirms (for those who doubted it) the history of David's character (although there have been attempts to find different and different alternative explanations), but it does not resolve the questions concerning the nature and scope of his kingdom, and the polemic will probably continue for a long time.

The kingdoms of Israel and Judah are also affected by the "shocks" that afflict the United Kingdom, although the controversy surrounding them is less heated. Those who dispute the existence of the united Kingdom of Israel in the tenth century must point to the time and circumstances of the growth of the two separate Israeli kingdoms. Examining the archaeological data according to the standards of comparative socio-political research led Finkelstein (following Jamieson-Drake) to the conclusion that the conditions for the development of a developed state matured only in the ninth century BC in the Northern Kingdom (Beit Omri), while Judah did not develop at all A real country before the destruction of Israel at the end of the eighth century BC (152, 147). Regarding the historical succession in the two Israeli kingdoms, we also have at our disposal for the first time occasional extra-biblical evidence - Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Aramaic (the inscription from Dan) and Moabite (the inscription from Misha), as well as a growing corpus of Hebrew inscriptions from the Land of Israel, such as Samaria pottery, Arad inscriptions , letters from Lachish, and more recently, the seals from Jerusalem that belonged to well-known figures from the end of the First Temple, including "Barchihu ben Neriah the scribe", the personal secretary of Jeremiah the prophet. Admittedly, these external sources only form a thin fabric, but they generally support the historical skeleton in the Bible.

From an archaeological revolution and post-Zionism?

Few of the writers in the collection refer to the growth of Israeli monotheism (Herzog, 61 and compare Kalai, 161), and indeed, it is appropriate that this complex issue be brought to the general public separately. Another issue that comes up in some of the articles is what Herzog calls the "scientific revolution", that is, the accelerated transition from "biblical archaeology" to "social archaeology" (Herzog, 61 ff.). This development has many positive aspects, but also less happy aspects. There is no disputing the importance of new research methods harnessing the technologies of the natural sciences, and this is also true for expanding the archaeological-historical discussion to economic, social and ecological issues. On the other hand, less exciting is "the disconnection of archeology from the shackles of the Bible" (Herzog, 62) and the written sources in general. It goes without saying that "both fields of research must develop their research independently and independently, and only then check the mutual significance of their findings" (ibid.), but who exactly is supposed to check this mutual significance and when? There is no supreme authority that is outside the cauldron of debate, and the synthesis is created gradually from a continuous dialogue between the disciplines and not somewhere at the end of days when each discipline will "solve its problems" separately.

Unfortunately, the turning of the rear to biblical archeology and history in general is to a large extent responsible for the fact that the number of young students and researchers who combine archeology, the Bible and history in their studies and research is decreasing (and perhaps this is also evidenced by the fact that all the writers in the collection, who are young at heart, are fifty years old or older). I am afraid that if there is no fundamental change in the approach of the research institutions, in the next generation the number of seminars and publications such as the one represented in the file will decrease greatly. I wish you were lost.

Many of the writers refer directly or indirectly to the connection of the controversy over biblical history to the questions of Israeli national identity today. I agree with the striking words of A. Mazar (97), which probably express the opinion of most of the writers in the collection: "The power of these events is actually their presence in the scriptures and their acceptance by the entire nation as a common heritage. The question of the degree of historical reliability of the sources of the Bible must therefore be seen as a purely research issue, which does not carry an ideological charge". I will not elaborate on this interesting issue, which also occupied a central place in the many response letters published following Herzog's article.

Nevertheless, it is impossible not to comment briefly on Uriel Simon's (surprising) article under the title "Post-biblical and post-Zionist archaeology", in which he makes an equal distinction between the "subversive archaeological findings" (137) presented by Herzog and researchers who share his opinion and between positions "Post-Zionism". A typical sentence summarizing his words: "Zionist archeology sought to reveal our roots in the land in order to deepen our grip on it, while post-Zionist archeology seeks to cut roots so that we can take off without hindrance" (ibid.). take off where? There is in this a dishonorable and even dangerous impeachment of the hidden motives of serious researchers whose Zionist commitment does not need qualification from anyone. Woe to us if researchers in Israeli research institutions subject their scientific integrity to the ideological image that their conclusions may create in the eyes of the keepers of the "Zionist foundations". My dispute with Herzog and other followers of severing archeology from the shackles of the Bible is disciplinary-epistemological, and has nothing to do with "post-Zionist" views and contemporary political positions. Like Herzog, my national consciousness is not conditioned by the historical truth of the exodus from Egypt or the dimensions of David's kingdom.

I admit that exposing a contradiction between the Bible and archeology does not pain me as much as it pains Simon (136), and to the same extent, exposing a compatibility between the two does not fill me with either happiness or sadness. I try to avoid "hostile interpretation" or "sympathetic interpretation" (138), which inevitably lead to squaring the circle. Only the feeling that I did my job faithfully and reached defensible results gives me professional satisfaction. As for my national pride, it is based on the fact that the central ethos in the story of the Exodus is the idea of universal freedom (and not necessarily heroism, as in many national ethos), that the "trial of the king" in 3000 Samuel XNUMX is the first manifesto against tyrannical tyranny (thousands of years before the French Revolution ), and that the prophets of Israel preached the teachings of morality and justice without fearing images in the eyes of the establishment or public opinion. What's more: these lines are written in the same language that was spoken in the streets of Jerusalem XNUMX years ago, and it doesn't matter to me if it was the capital of an empire or a small mountain fortress.

The author is a professor in the Department of Archeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations at Tel Aviv University.

4 תגובות

Justifies your life, of course it will be true... After all, truth is a personal word, everyone finds the truth before he even started looking for it... Now he just found another pillow to cuddle with (and the wise will understand)

Spirited things indeed!

Every word is true (or at least apparently true)

Great article.

respect!