The popular media, including Haaretz, have given the ENCODE project credit for things it does not have. Ido Hadi wants to make order

A few weeks ago, the results of one of the most ambitious projects that researched the human genome, the Encyclopedia of DNA elements project (ENCODE) were announced. The project continues the human genome project and the goal of the researchers was to collect data on the human genome beyond its sequence. Although his importance is great, many of the popular accounts have exaggerated his value and given him credit for things he did not do. The most annoying thing attributed to this project is finding a function for non-coding DNA. In "Haaretz", for example, it is claimed that the more the researchers "examined the 'junk' parts of DNA, which are not genes that contain instructions for proteins, they discovered that it is not junk at all and that at least 80% of its parts are necessary and active." This is not an accurate description.

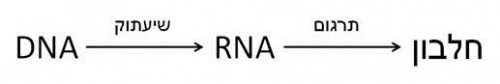

Our genome is made of DNA. Molecular machines are able to create RNA copies from the information encoded in DNA in a process called transcription. The ribosome, another huge molecular machine, is able to produce proteins according to the information stored in the RNA in a process known as translation (see figure). However, most of our DNA does not code for proteins and is therefore called "non-coding DNA". Already in the 70s and 80s several important biological functions of non-coding DNA were known. For example, ribosomal RNA was known, which is one of the components of the ribosome, the same molecular machine that produces proteins. Another example is the centromeres, unique sequences that are in the center of each of our chromosomes and function during cell replication. They don't need to be transcribed to function. In recent years, several other functions of the non-coding DNA have been discovered, mainly those that are mediated with the help of different RNA molecules. Ribosomal RNA, centromeres and functional RNA molecules not unique to humans. They exist in a variety of organisms, from worms to mammals and beyond.

From all this it is clear that biologists did not assume that the non-coding DNA had no function. The confusion on the subject in media reports probably stems from the connection between non-coding DNA and junk DNA. Junk DNA is the popular name for non-functional DNA. While it is true that junk DNA is non-coding DNA, the opposite is completely false. As demonstrated above, there are segments of non-coding DNA in our genomes and those of other organisms whose function has been known for decades.

From all this it is clear that biologists did not assume that the non-coding DNA had no function. The confusion on the subject in media reports probably stems from the connection between non-coding DNA and junk DNA. Junk DNA is the popular name for non-functional DNA. While it is true that junk DNA is non-coding DNA, the opposite is completely false. As demonstrated above, there are segments of non-coding DNA in our genomes and those of other organisms whose function has been known for decades.

This leads me to another claim attributed to the ENCODE project. Some have argued that the project disproved the existence of junk DNA or at least showed that the human genome has relatively little junk. In a report in "Yedan" Elise Feingold from the National Genome Research Institute in the US was quoted as saying that "the most amazing thing we found was that we can attribute biochemical activity to about 80 percent of the genome, and it dispelled the idea that there is a lot of junk DNA or if there are DNA sequences at all which we can call garbage". The scientific journal Science also devoted a nice article to review the results of the project under the title "The ENCODE project writes an obituary for junk DNA". Even the members of the successful Israeli podcast "Spec Sabir" (recommended!), who usually do excellent preliminary investigation work, attributed this result to him. Does ENCODE really deal such a strong blow to the concept of junk DNA?

back to the past

To answer this question it is necessary to go back a few years. In 2007, the results of the ENCODE pilot study were published that surveyed XNUMX percent of the human genome. The most important finding found there is that most of the surveyed genome is transcribed, that is, RNA is created from it. This was an interesting result, especially because of the nature of many of the sequences that were copied. The initial sign that a certain sequence has a function is evolutionary conservation, that is, a great similarity between a certain sequence and its corresponding sequence in other organisms. Evolutionary conservation implies that natural selection "made sure" that the sequence would no longer change throughout evolution. There is no reason for natural selection to do this if the sequence does nothing, so evolutionary conservation of a particular sequence is considered one piece of evidence that it has a function. However, the ENCODE results showed that even regions of the genome that are not evolutionarily conserved were transcribed. The transcription of a significant percentage of the genome is taken as evidence that the transcribed sequences have a function.

The use of extensive transcription of the genome as evidence of function created immediate controversy. Opponents had two main criticisms. The first was a methodological problem. According to the opponents, one of the methods used by the ENCODE researchers could make regions of the genome that are not copied appear as if they are copied. The second was that most of the genome is indeed transcribed, but most of it is transcribed in a minimal amount. Such a small amount of RNA transcripts, they argued on several occasions, corresponds to random and non-specific transcription by the molecular transcription machinery. It is not evidence of function, but the product of a transcription that started in a random cell. The response from ENCODE supporters was not long in coming and response to response was published along with it.

Genome-wide transcription was not the only finding of the pilot seen as evidence of function. For example, interesting patterns of binding of transcription control proteins to a multitude of regions throughout the length and breadth of the human genome and patterns of genome-wide changes in the chromatin proteins, the proteins that wrap the DNA and are involved in the control of transcription, were also found. These patterns also seemed to indicate a function. The changes in the chromatin proteins and the binding of control proteins are one of the things that make transcription possible. Therefore, argued the opponents of the ENCODE researchers' interpretation, these patterns are expected to be found in regions that are transcribed, whether the transcribed RNA has a function or not. Clearly, the implications of the ENCODE findings for the distribution of junk DNA in the human genome are controversial. Little me tends to side with those who oppose the use of genome-wide transcription and the other results of the ENCODE project as evidence of function. They seem to me to be more cautious in drawing their conclusions.

back to the present

The ENCODE pilot screened only 147 percent of the human genome. The recently published results surveyed the entire human genome in 80 cell types. The researchers claim that more than XNUMX percent of the genome has a "biochemical function". The body of data collected by ENCODE researchers has expanded greatly, but it is not immune to the criticism leveled at the pilot. The criticism leveled at the ENCODE pilot can still be leveled at its latest results as well. There is scientific controversy surrounding the question of whether the results of the ENCODE project can be used as evidence that large regions in the genome have a biological function. In other words, there is controversy surrounding the question of whether his results are relevant to the discussion of the distribution of junk DNA in the human genome.

The study itself does not mention junk DNA. As I mentioned above, the researchers report that they have identified a "biochemical function" for 80 percent of the genome. "Biochemical function" is a vague phrase at best, at least when the general public, who has no background in biochemistry, tries to understand the implications of the fact that 80 percent of the human genome has a "biochemical function" on the distribution of junk DNA in our genome. It is surprising, then, that the press release that accompanied the study presented it as a refutation of the claim that most of the genome is junk. This interpretation of the findings and the phrase "biochemical function" was not presented as it is, as a controversial interpretation. Someone in the PR office created a lot of headlines in the popular science sections announcing the demise of the genomic junk. Few journalists dug deeper and mentioned the controversy.

To the future and beyond

The ENCODE project was planned from the beginning as a multi-phase project. The recently published results are only the second phase of a much broader project. Although the significance of his findings to the junk DNA question is controversial, the importance of the project as a whole is not. By all accounts, the vast database created by the project's scientists will serve researchers in the future and help to slowly advance our understanding, among other things, of disease processes and human evolution. Also, in the project, several DNA sequences with potential function were identified. Because their function is unknown, these sequences are called genomic dark matter. The importance of the genomic dark matter will become clear in the future, when further studies will verify that they indeed have a biological function and examine in depth what exactly they do. ENCDOE is only a beginning, not an end.

for further reading:

- Evan Birney of the ENCODE Project wrote otherPosts In them he explains his opinion on a variety of topics related to the project, including topics covered here.

- Mike White, a biochemist by training, Wrote a good review On ENCODE and Junk DNA.

- Ed Jung, science journalist, Posted a bad post on the subject, which was corrected later.