A colony of bacteria that is in competition with other colonies creates a deadly protein that causes its neighbors to "keep their distance" from it. Researchers report this week that by inhibiting the growth of neighboring colonies, and even eliminating their cells, the colony preserves the few resources available in its environment, even when the neighboring colonies are its "sisters".

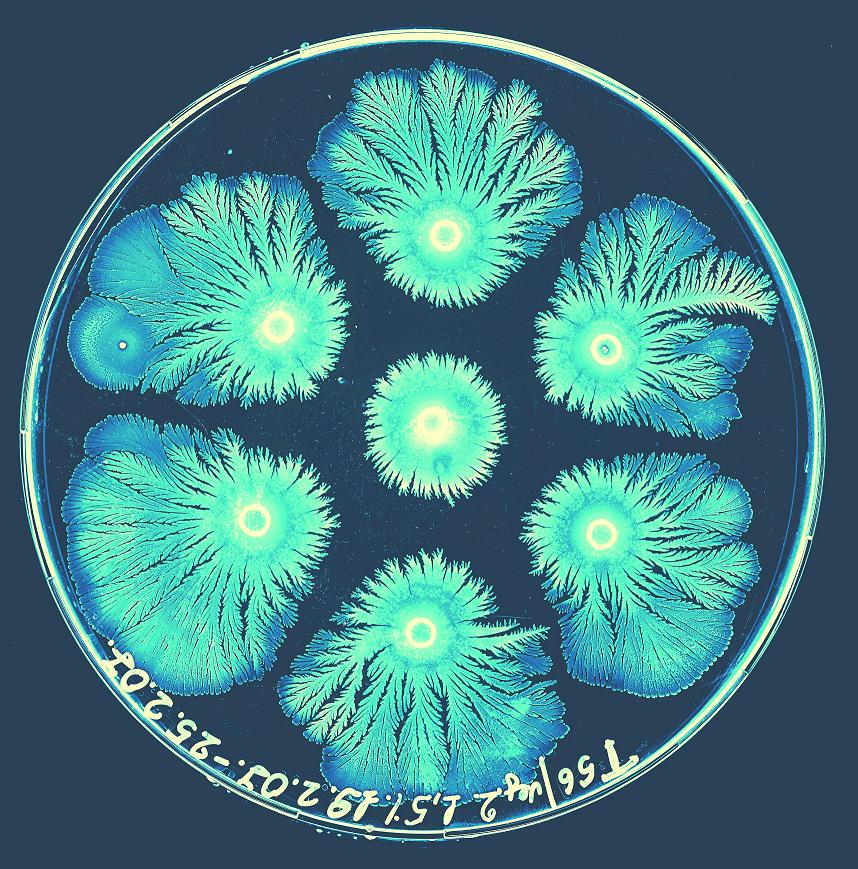

The studied colonies belong to the special strain Paenibacillus dendritiformis, discovered by Ben-Yaakov. When you put these colonies alone on a petri dish, they will send out branches of cells in all directions. However, when two colonies share one plate with a limited amount of food, the branch pattern of the two colonies is distorted and a space remains between them.

It is not a lack of food that stops the growth because the researchers found leftover food between the two colonies. They also found in the same area a protein that was not present anywhere else on the plate. When they put the same protein on a plate where this strain of bacteria was growing, the new colony formed a strange shape that avoided approaching the protein and the cells closest to the protein died.

The researchers called the protein a "deadly relative" due to its ability to kill sister colonies produced from the same mother colony. During the research, the gene that codes for the protein was identified, but this gene actually codes for a larger and heavier protein than the deadly protein and actually codes for a non-dangerous protein. The researchers concluded that there is another factor at play that plays a role in the lethal mechanism.

The strain of bacteria in question secretes a protein called subtilisin, which encourages growth at low concentrations. The subtilisin, known to science, is found in a high concentration between the two colonies and therefore cuts the heavy protein into the chelating and smaller form. In its small form, the protein destroys the cell wall and spills its contents into the environment.

6 תגובות

I asked my father to ask Prof. Eshel Ben Yaakov for further clarifications so that he would not be required to speculate.

He said he would and I hope we get a full explanation.

Indeed, there is no growth in the center of the colony, but in the margins, pay attention to the picture. As it is possible that the white circle in the center of the colony is a result of lysis (death) of the bacteria as seen in E. coli colonies and other bacteria.

Rah:

This is more or less one of the scenarios I described but it is not written in the article.

It also doesn't quite work out (and that's why it's only more or less what I said) because the concentration in the middle of the group is supposed to be higher than on the fringes and if the fringes kill - the middle is easy.

That's why I talked about the possibility that it only hurts during the division.

The researchers in the article developed a mathematical model in which the substance affects a certain concentration. Therefore a colony can grow and excrete until the material reaches the critical concentration and then it stops. An adjacent colony, also small, will stop at that stage even though it has not reached the maximum size because the concentration of the inhibitor in the substrate from the first colony has reached the critical concentration.

The concentration of the material in the interface between the colonies will be higher than the other side of the colonies and this is the reason for what you see in the picture.

It is not entirely clear from what is written how sebastilizin harms neighboring colonies of the same type and does not harm the bacteria in the colony itself.

It may be due to the fact that the bacteria inside the colony also consume it in some way and prevent it from accumulating to lethal amounts while outside the colony it manages to accumulate (something reminiscent of the surface tension of liquids - if anyone understands what I mean) but it is not written here and it is not clear if this is what is happening .

Another possible scenario is that the protein does not damage whole cells but only those that are dividing and then - a lethal concentration prevents both the continued growth of the colony and the settlement of other colonies near it.

There are probably other possible scenarios, including the correct one, but it's a shame that the matter was not clarified.

Fascinating and elegant