The great hornet provided humans with a source of meat and eggs. From around 1500, however, hunting increased dramatically as Europeans discovered Newfoundland's rich fishing grounds. Within 350 years, the largest beetles ever seen were killed and put into a museum, and the species was lost forever.

By Jessica Emma Thomas, Postdoctoral Researcher, Swansea University

A well-preserved oak detail on display at the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow. Mike Pennington / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

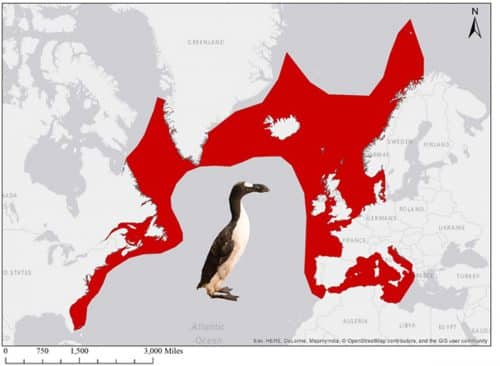

The North Atlantic Ocean was once home to a bird that was remarkably similar to penguins. The Great Auk, also known as "the original penguin", was a large black and white flightless bird that contained populations of millions of individuals. Despite its appearance, the great auk was actually a relative of the sharp-beaked auk and the sea parrot, not of penguins. Since around 1844, the northern hemisphere has been without its own version of the penguin and it seems we are to blame.

The great hornet provided humans with a source of meat and eggs. From around 1500, however, hunting increased dramatically as Europeans discovered Newfoundland's rich fishing grounds. Within 350 years, the last large beetles ever seen were killed and put into a museum, and the species was lost forever.

In light of the relative speed of this extinction, it is worth asking whether other factors such as changes in the environment were involved. Did the great elk tend to extinction before intensive hunting began? Or could it have survived and still be around today if not for humans?

In a recent study, my colleagues and I found no evidence that the great elk was already in retreat or in danger of extinction before the intensive hunting. The findings indicate that no other factor was involved in their deaths. Human hunting pressure alone was enough to cause their extinction.

Our findings highlight how industrial-scale commercial exploitation of natural resources has the potential to drive an abundant, highly mobile species to extinction in a short time.

Ancient DNA

Through the study of extinct species we are able to learn things that can help us in the fight to preserve species that are currently facing extinction. One way to do this is to examine the genetics of extinct species. With ancient DNA (ADNA) we can look at things like genetic diversity (how many genes have changed between different individuals in a species), which can reveal trends in how genetically healthy the species is. Genetic research can also show us how a species can respond to environmental change, hunting or the introduction of new species into its habitat.

There is a lot of evidence, including archeological records and written evidence, showing that the great elk was hunted by the oak throughout its existence. But until now we didn't know what effect environmental change might have on the bird's extinction. If the species was endangered before intensive hunting began in the 16th century, we would expect to see signs in its DNA.

Large oak bones used to obtain ancient DNA. Jessica Thomas, courtesy of the author.

For example, if a species has low genetic diversity and most individuals are very similar, then the species is less likely to survive an environmental change.

Conversely, large differences in the DNA of individuals from different locations can also indicate that the species is divided into isolated populations that do not migrate and do not mix their DNA with other groups. This population structure will cause the genetic pool of the species to shrink and the accumulation of "bad" genes, which becomes an important factor in the vulnerability of a species to extinction.

These kinds of changes in genetic diversity are among the signatures we look for during extinction research. If we can't find a decline in diversity during the last hundreds of years before the extinction, it suggests that the population shrank rapidly, which would point to humans as the culprit.

We can use statistical models called population viability analyses, which look at the probability that a species will become extinct at a certain time. These models can be used to show whether large-scale hunting can be the sole cause of extinction.

To find out which of these scenarios occurred in the case of the great auk, we sampled its mitochondrial genome. This included taking samples from bones found by archaeologists as well as skins and organs stored in museums around the world. We successfully sequenced the DNA of 41 individuals, representing birds from across the main areas where the aleka lived from 15,000 years ago to 170 years ago.

There is no gradual decline

We found that the genetic diversity was high in all samples, with evidence of a constant population size and no evidence of population decline or evidence of a prominent population structure. This suggests that the greater elk was not endangered before intensive human hunting and that its extinction due to population decline is too rapid to appear in our data. Meanwhile, the population viability analysis revealed that hunting alone could have been enough to cause the species to become extinct.

Today, seabirds are more threatened than any other bird group, with a third of the species endangered and half facing decline. Threats to seabirds include climate change, habitat loss, pollution, human fishing and direct exploitation from egg collection, and hunting of chicks and mature birds. Seabirds play a global role in ecosystems, acting as predators, scavengers, and ecosystem engineers, so it is very important to understand more about why they are becoming extinct.

Our research describes hunting by humans as the main cause of the extinction of the great elk. It also reminds us how real the threat to seabirds is today. The findings also show why we need to closely monitor commercially hunted species, especially in environments where research is limited like our oceans. This will help us better understand what is happening with the threatened species in the world and we hope to act before they are going to be considered history in the wake of the Great Elka.

To the article on THE CONVERSATION website

More of the topic in Hayadan:

3 תגובות

To anonymous who responded to anonymous

There is a tendency on the site to upload articles without critical reading or at least proofreading

In the time gap between the first response and your reading, they probably corrected the mistake

Anyone who reads the article will see

that there is always a reference to "big elk"

So why the unnecessary response

of the anonymous user? ? ?

In Hebrew the bird is called a large elk.

When there is already a name, there is no need to invent a new name.