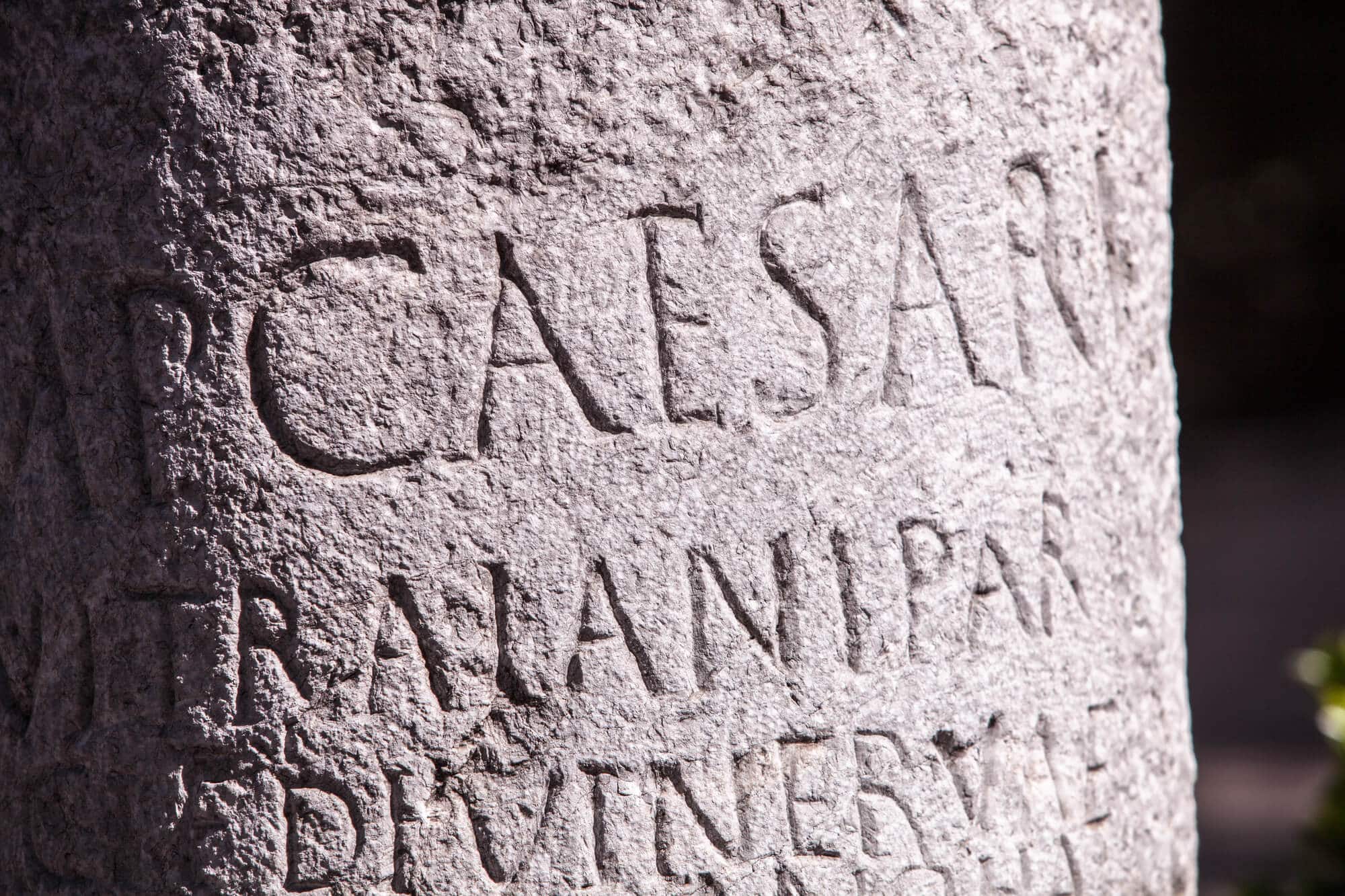

The road signs illustrated the power and domain of the Roman Empire

People who walked, rode or drove on one of the many roads of the Roman Empire could be helped by continuous signage that accompanied them. Every mile (a thousand double steps) along the road, a sign was placed with some details, in Latin and sometimes also in Greek: the name of the main city from which the road left, the distance from it and equally important, the name and various titles of the emperor in whose days the road was paved or repaired. With each additional renovation, these stones multiplied - cumulative evidence of the power of the Roman Empire, and in our eyes today, historical documents written in stone.

These stone signs are a kind of "archaeological relics from the ancient world" - as defined by the Israel Prize laureate historians Prof. Binyamin Isaac from Tel Aviv University and Prof. Haim Ben-David from Kinneret Academic College, and the archaeologist Dr. Guy Stibel from Tel Aviv University.

"These stones are a glimpse into one of the main contributions of the Roman Empire to the Western world - the infrastructure," says Dr. Stibel. "In the ingenious formulation of the Monty Python gang in the movie 'Brian Superstar', what have the Romans ever done for us - what have the Romans ever done for us? Apart from the aqueduct, the sewers, the baths, the irrigation, and the roads - apart from all these, the characters in the film ask, what have the Romans already done for us?

"Well," adds Dr. Stibel, "the roads were the skeleton and blood vessels of the empire. In many cases, it was the Roman soldiers who paved them, and their first purpose was military. But from the moment the roads were paved and maintained, the infrastructure was created for the movement of merchants and travelers, who moved around the world under the auspices of the 'Pax Romana', the famous 'Roman Peace'. Along the way, the travelers were accompanied by posts of the Roman army, who protected the travelers from robbers and collected taxes; hostels for accommodation; And the millstones - propaganda signs that reminded people of whose courtesy they were traveling here.

"The inscriptions on the stones provide us with information with a rare resolution of time and place," says Prof. Ben-David. "On each stone appears the name of the emperor of that time together with all his titles - and according to the titles that appear and those that do not yet appear, because they were awarded to the emperor only at a later date, it is possible to know when the stone was placed, sometimes with an accuracy of a few years.

"Many of the important roads have been in use for hundreds and thousands of years. The question 'since when is this way?' It is therefore misleading. What are we actually asking - when did people walk it, or when did the paving stones come from, or when did the inn on the side of the road come from? Thus the findings are often confusing. But the Roman milestones, thanks to the detailed inscriptions on them, provide us with a very accurate dating."

Prof. Isaac tells about an interesting example of such a date. "The oldest millstone discovered in Israel was found in the 70s near Afula, and on it appear the name of the emperor Vespasian and the name of the commander of the tenth Roman legion, General Trajanus - the father of the emperor of that name. From the combination of the names and titles we conclude that the stone was placed in 69 AD, the year Vespasian was crowned emperor, during the great revolt of the Jews against the Romans. From the stone we learn that General Trajan remained as a commander in Judea to maintain peace as much as possible during the great rebellion, that is, he was very close to Vespasian and took care of his affairs in the country; And that, apparently, was the basis for his successful career later on."

Prof. Ben-David describes other findings, which served as decisive evidence in the study of the existence of an ancient road in the Negev. "Researchers who studied the ancient road from Petra to Gaza," he says, "believed for a long time that it was a Nabatean road. But a long section of this road has never been found. In 2018, Ziv Scherzer, training coordinator at the Sde Sde Boker school, managed to decipher part of the mystery. Scherzer hypothesized that the road took an alternative route, which had not been tested until then. Scherzer and some travelers and guides set out to test his hypothesis, and indeed found some Roman millstones along this route. As a result, I came to the place with my students, and we found additional fascinating findings. The findings showed that even if the road or part of it was formerly Nabatean, the Roman Empire adopted it and made it its own. This hypothesis and discovery illustrate the enormous importance of field schools as training for the Israeli academy. Many talented people start their careers as field workers, who know the field 'through the legs'."

The current study, which was awarded a research grant from the National Science Foundation, is intended to bring to the research community and the general public all millstones in the Land of Israel, which began over 100 years ago and has continued even more intensively in the last 50 years, under the auspices of the Society for Roman Millstones since the founding of Tel Aviv University and led by the late Prof. Israel Roll and Prof. Binyamin Izak. One of the largest concentrations of millstones is found in the territory of the State of Israel. The study of this complex helps in the reconstruction of one of the phenomena that shaped the landscape of the country, and in the reconstruction of roads, many of whose routes are still used by us today.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- Environmentally friendly concrete - like the one used by the Romans

- Wine and fish sauce - evidence of the culinary preferences of the Romans 2000 years ago was uncovered in Ashkelon

- Economy 16 Chapter XNUMX: Under the Romans after the destruction of the Second Temple: Small or large farm

- The Forgotten Rebellion - Dr. Yechiam whistles about the Jewish rebellion in the Diaspora against the Romans and the Hellenists

Life itself:

Prof. Benjamin Isaac listens to classical music, plays the viola and swims regularly.

Prof. Haim Ben-David enjoys challenging trips in desert landscapes and organizes travel camps for his grandchildren.

Dr. Guy Stibel travels around the country and enjoys listening to jazz music.

,