Studies show that unconscious memory is not impaired with age, and remains relatively normal even in Alzheimer's patients. Unconscious memories and other unconscious processes may influence every action we take

Anyone who learned to ride a bike as a child knows the phenomenon: you can stop riding a bike for years, but the mind and body don't forget. This is a familiar example of unconscious long-term memory: when we get back on the bike, we can start riding without putting any thought into it. We don't have to consciously think about each movement separately. Another example, sit in front of the computer and type your name or email address. It is likely that most people with reasonable typing ability will do this without any difficulty because this task relies on unconscious memory. Now, without looking at the keyboard, write on a page what the ten letters are on the top row of the keyboard. This is already a much more difficult task, which requires the use of conscious (explicit) memory and attention, and therefore most of us will not be able to indicate more than one or two (if any) numbers found on the top row of the keyboard.

Professor David Mitchell from the University of Kansas in Georgia, has been researching unconscious memory for many years and has discovered surprising findings, such as the fact that unconscious memory is not damaged in Alzheimer's patients until a very advanced stage of the disease.

Six beers

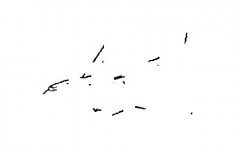

How do you study unconscious memory? One of the accepted ways is to test priming, that is, a process in which subjects are exposed to a stimulus that should affect their response to the stimulus given at a later stage. The test developed by Mitchell tests how well subjects are able to identify a certain image based on line segments from that image (see figure). In the conditioning phase, subjects are exposed to a series of 100 image pairs. In each pair of subjects, they first see only sections of the full picture, and try to guess what it is, and then see the whole picture. After a week, the subjects are exposed to a series of 200 image segments, (namely new images), and it turns out that the recognition ability of image segments that have been primed is twice as high as that of new segments. The first time they ran the experiment, Mitchell bet a colleague that the experimenters would indeed guess more pictures after a week. Following the intervention he won six beers.

But it turns out that Mitchell could have bet for a much higher prize. The follow-up experiments he conducted show that the healing effect did not wear off after a week. Not even after six weeks. And recently Mitchell has shown that she is not expired even after 17 years, even if her influence is fading. People are able to identify distorted image segments more easily. Some of the students who participated in the experiment 17 years later did not even remember participating in the first experiment, but their unconscious memory allowed them to recognize the image segments more easily.

Why does the brain remember such seemingly trivial things? What advantages are there to talk about? There is clearly a benefit to our ability to automatically perform routine repetitive actions, such as walking, making a sandwich or riding a bike without thinking about every detail. There is also a clear benefit to our ability to recognize objects or people based on partial information. Such actions do rely on unconscious memory, but what is the use of the brain remembering fragments of images for years? Mitchell does not know how to explain this, but he is convinced that there is some evolutionary advantage here.

The memory that is not affected by memory loss

A student of one of Mitchell's colleagues worked with patients who suffered from memory impairment. The student, who loved to tell jokes, believed that he could take advantage of the rare opportunity that fell into his lap and tell that joke over and over again. Indeed, the first time he told the joke to one of the patients, the patient laughed with delight. But when he told the same patient the joke a second time, the patient did not laugh. He didn't know why he wasn't laughing, but the joke didn't make him laugh anymore. His unconscious memory went through the trauma and remembered what the conscious memory had forgotten.

Mitchell examined the effect of age and conditions such as Alzheimer's on the ability to undergo visual processing of image segments. Countless studies show that with age there is a decline in conscious memory, but what happens to unconscious memory? Mitchell shows that hypothermia is not impaired in people suffering from amnesia or age-related cognitive decline, at least for a period of one week. Even mild to moderate Alzheimer's patients have a normal temperature for three days. Such findings could have an impact on the way Alzheimer's patients are treated.

Conscious memory is influenced by the subconscious

Some studies have already shown that the manipulation not only affects unconscious memory, but also behavior. For example, studies by John Berg, a psychologist at Yale University, showed that when young people are exposed to a list of words that characterize old people (eg, gray, weak), the subjects will walk more slowly than subjects who were not exposed to the list. Similarly, if subjects are given a cup of hot drink, they will assume that the person in front of them has a warm personality, while subjects who hold a cup of cold drink, believe that the person standing in front of them has a cold personality.

During Professor Mitchell's visit to Israel, he and Dr. Jacob Hoffman and Dr. Ephraim Grossman, both from the Integrated Department of Social Sciences at Bar Ilan University, showed that trauma affects not only unconscious memory, but also conscious memory (explicity). In one of their studies, they show subjects a list of five words, presented in random order, from which they can form a sentence. One of the words in the list corresponds to a stereotype of an older person (for example: gray, retirement, grandmother) or alternatively of a young person (for example: sports, fashion, fast). The subjects are then tested on their ability to remember a list of neutral words. It turns out that the subjects who were exposed to the "old" words performed the memory test less well than their peers.

A few years ago a provocative study was published that showed that our unconscious mind makes decisions up to 10 seconds before we make the decision consciously. In the study, John-Dylan Haynes and his colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, asked subjects to make a simple decision: whether to press a button with their left hand or with their right hand, according to their free will. At the same time, the subjects watched a sequence of letters projected on a screen, and the only instruction they received was to pay attention to which letter was projected on the screen while they made the decision to press the button. At the same time, the researchers monitored the brain activity of the subjects with the help of functional magnetic resonance imaging. When they analyzed the results, the researchers saw that they could predict which hand the subjects would press the button 7 seconds before the subjects were aware of their decision. Since there is some delay in visualization, this means that the brain made a decision up to 10 seconds before it reached awareness.

Studies like this and studies of the type conducted by Mitchell and his colleagues sharpen the question of what free will is, and whether it even exists in the common sense today. It is precisely the darker side of the field that provides some comfort. In 1957, James Vicari, who did independent market research, claimed that he had shown during movies subliminal advertisements that flashed on the screen for a fraction of a second and told the audience to drink Coca-Cola and eat popcorn. For years no one replicated Vicari's findings and it seems they were a hoax. However, in recent years scientists have begun to test the subject in a controlled test, and they show that it is indeed possible to influence the choice of drink brand of subjects, but only if they were thirsty to begin with. So, the subconscious may be controlling us, but only if we are thirsty...

Professor David Mitchell is a fellow of the prestigious Fulbright program, which promotes academic-scientific cooperation between the US and Israel and supports outstanding researchers and research students. The Fulbright program is managed by the US-Israel Education Foundation and is the first intergovernmental program to promote scientific ties between Israel and the US. The Fulbright program left its mark on academic research in Israel and in other key areas. Graduates of the program include Nobel Prize winners (http://www.fulbright.org.il). Professor David Mitchell was a guest at Bar Ilan University.

More on the subject

Short- and Long-Term Implicit Memory in Aging and Alzheimer's Disease, David B. Mitchell And Frederick A. Schmitt, in Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, vol 13, pages 611-635, 2006

Age Differences in Implicit Memory: Conceptual, Perceptual, or Methodological? David B. Mitchell and Peter J. Bruss in Psychology and Aging, Vol. 18, no. 4, pages 807-822, 2003

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

3 תגובות

I'm sure everyone on this site knows 6 letters on the top row of the keyboard... and maybe the entire middle row 🙂

Who knows the site Smarter Every Day?

Dustin showed how you can forget to ride a bike: by riding a bike with a different steering mechanism.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFzDaBzBlL0

In my opinion, memory researchers should jump on what he discovered (about himself)

exciting! I wonder if this information is already being used by salespeople.