Galit asks "what makes it different and why does it cause so many arguments"

As you probably guessed, the difference is one of the rules of football. But the difference is much more than just an arbitrary rule: it is the law of the difference that gives the soccer game its character and uniqueness and distinguishes it from any other team ball game.

Apparently, football was supposed to be one of a series of games such as handball, basketball, water polo or hockey in which each team needs to bring the ball to the target protected by the opponent. But soccer is unique: even though the goal is more accessible than the hoop in basketball and the movement is much easier than water polo, fewer goals are scored in soccer than in any other ball sport. In principle, football is more similar to chess than handball or basketball: most of the time and energy is spent precisely in what the broadcasters call "controlling the center of the field" - a concept that has no equivalent in other ball games where the players simply rush to the opponent's part of the field.

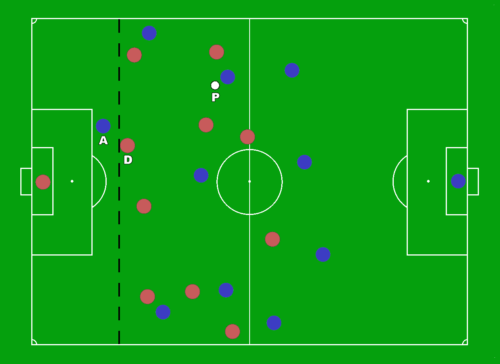

Basketball fans, for example, have a hard time understanding what football fans find in a game that takes place most of the time away from the place where the result is decided. Accordingly, many football matches end in a result that is not known in almost any other sport (again, except for chess): a draw. The reason for the strange behavior of football is the different law that was used in 1866 and which shaped the character of the game. In a simplistic and very imprecise formulation, the law of difference states that the player of the attacking team must not be closer to the opponent's goal than the ball itself and the two rearmost opponent players (including the goalkeeper). The rule is that an attacking player without the ball always needs an opponent's defensive player between him and the goal. It's hard to imagine what football would look like without the cleat: a cleat-free version was played in England in the 19th century and, as expected, the preferred tactic for teams was to keep attacking players permanently close to the opponent's goal. The law of difference obliges the attacking team to be very careful in building the attack and makes the work of the defense easier. When, in 1925, the English association eased the different rule that until then required 3 opposing players between the attacker and the goal, the average number of goals per game jumped from 2.5 to 3.4.

But the second part of your question, Galit, is much more interesting: why does the difference arouse so many arguments and why was it necessary for the world soccer association FIFA, known for its conservatism, to approve the VAR: a referee's ruling based on video photographs. One reason is the degree of complication of the rule: not every player who is "too far ahead" is guilty of the difference. For it to stand out, the player needs to be actively involved in the game. The "passive difference" is a vague situation and subject to the judge's wide discretion. But complicated rules exist in other branches and the difference, as Galit noticed, differs from other sports rules in the fact that the judges are often wrong about it. It turns out that the rate of mistakes by judges (without the aid of cameras) in determining a different situation is no less than 25%. Since these statistics also include very clear situations, in "borderline" situations the chance of a judge to make a decision based on his eyes and the assistance of the linemen is not much higher than what he would achieve by tossing a coin.

What makes determining a distinct so problematic? The question, Galit, is so interesting that even Nature - the most prestigious scientific journal in the world - published an article that tries to crack the riddle of the difference. Raoul Oudejans (Raoul Oudejans) analyzed 400 video rulings and showed that the linesman's flag-waving mistakes are not random. When the event took place in the half of the court far from the line, the mistakes were clearly biased in favor of the defense: 6 times more false flags that stopped a "kosher" attack than undetected different situations. The situation is reversed when the attack took place in the half of the field near the line: here you should be in the shoes of the attacking player: 4 times more distinct situations passed without raising a flag compared to all wrong ones. The data refer to those situations in which the attacker burst "from the outside" - when the attacker is closer to the center than the defensive player, the trend of errors reverses. Odgens explains that the image makes perfect sense when analyzed as it is reflected in the line's retina.

The difference errors, according to Odgens, arise from a simple geometric problem of projecting the diagonal line between the attacker and the defender on the flat screen in the eye, and therefore it can be solved by using video photography. Apparently the riddle has been solved, but scientists have a high ability to complicate simple theories. The researcher Werner Helsen claims that Odgens' geometric drawings are insufficient. The laws of optics cannot explain, for example, the statistical finding that the first 15 minutes of a game are prone to mistakes more than any other time period throughout the 90 minutes. In addition, the optical explanation is a bit too elegant: the chance of making a mistake in favor of the defense is equal to the chance of the referee to make a mistake in favor of the attack, but in real life the mistakes clearly disadvantage the attacking side (tracking all the World Cup games in 2002 revealed that the defense benefits in 86% of the difference's mistakes).

Helsen suggests, therefore, another error factor that originates not in the image received by the eye but in the mechanism that analyzes it in the brain. The phenomenon is called the Flash lag effect: when a sudden stimulus requires us to place a rapidly moving object in space, the brain will place it "ahead", that is, in the place where it should be after a while if it continues its movement. There is an evolutionary logic to this mirage: the sudden appearance of a fast body portends danger and you should prepare for the situation as it will be when you are forced to react. Evolution prepared us to be hunters or the hunted and not for the role of football lineman. In the referee's mind, the attacking player was caught rushing forward at the moment of the pass as if he had already crossed the goal line, although in reality he was slightly ahead of him. The lineman, as it is called, moves along the field as he tries to find himself on the "distinct line" (that is, with the rearmost defensive player) to avoid optical illusions. But it turns out that the lineman's close look may be too close. A study that examined all the referee's decisions over a whole year in the German league revealed that the optimal distance for identification is actually further away from the line along which the line moves, so that the fans sitting in the stands behind the line (and expressing their opinion on the quality of the refereeing and the referee's relatives) have a better chance of jumping. Why does proximity to the event reduce accuracy? Because the players and the ball spread over too wide an angle in the linesman's field of vision, while for the viewer from afar the event occupies a smaller part that can be focused on.

But there are also those who go even further, Francisco Maruenda (Francisco Maruenda)) is a doctor who studied the problem of the different in terms of the amount of time required to notice it. In order to identify a difference, the referee is required to determine the relative position of 5 moving objects: the offensive player who kicks, the player who receives the ball, 2 defensive players (one of them the goalkeeper) and of course the ball. These 5 bodies are spread over an area of about 3 dunams. Dr. Marwande added the amount of time required for the eye to focus on the kicked ball (it is the last time point at which the player is not allowed to find the difference), the amount of time required to rotate the eyeball so that the offensive player and the defensive players are in the center of the field of vision and the time to refocus the gaze after the move. Thus, for example, at least 200 milliseconds are required for the referee's eyes to shift the focus from the kicked ball to the receiving player: enough to run 2-3 meters. The total time required for distinct vision is 0.6 seconds: a period of time in which the relative distance between the players changes by many meters. Such calculations led Marwanda to a conclusion that would shock every football fan: the human vision system is unable to recognize a distinct situation in real time. According to Francisco Marwanda, soccer refereeing is a kind of alchemy: a diligent and heroic attempt to achieve a physically impossible result.

Thanks to Dr. Francisco Belda Maruenda and Dr. Werner Helsen for their help.

Did an interesting, intriguing, strange, delusional or funny question occur to you? Send to ysorek@gmail.com

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- In some situations bats prefer the sense of sight over the sense of sonar

- The physics behind football

- Watch a soccer game from the point of view of the ball

- Things that birds know: why do pigeons bob their heads?

- I found this brilliant brilliance on YouTube, thanks to everyone who took part in it. Offside is different in English, the word was probably not yet invented when the sketch was written.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6buZsORQgwc

One response

On the one hand, the linesman does not need to include the goalie in his system of considerations because he can assume that the goalie is in any case in front of the attacker - therefore the area on which he is supposed to recognize is smaller than what is written here. On the other hand the line was the default when they started playing football. Today there are enough electronic aids that can detect different situations. The question is whether anyone wants to use them.