The Internet is essential not only for the digital revolution but also for our continued prosperity - and even for our freedom. And like democracy, the network also needs protection

The World Wide Web came to life in December 1990 on my computer in Geneva, Switzerland. It consisted of one website and one browser, which happened to be installed on the computer. This simple arrangement demonstrated a profound concept: anyone anywhere can share information with anyone else. The network spread in this spirit and grew rapidly. Today, on its 20th birthday, the web is integrated into every aspect of our daily lives. We take it for granted and expect it to "be there" every moment, similar to electricity.

The network became a widespread and powerful tool because it was built on the basis of egalitarian principles and because thousands of private individuals, universities and companies acted, individually and together, within the consortium of the worldwide network to expand its capabilities based on these principles.

However there are factors that threaten the web as we know it. Some of the most successful users began to undermine its principles: large social networking sites block information that their users publish and do not allow it to reach the rest of the network; Wireless internet providers are tempted to slow down traffic to websites they don't have agreements with; And governments, both totalitarian and democratic, monitor people's online habits and endanger important human rights.

If we, the users of the network, allow such and similar trends to develop unchecked, the network may break up into separate islands. We will lose the freedom to connect to any website we want. The negative effects may also spread to smartphones and tablet computers, which also allow access to the large-scale information that the network provides.

But why should it interest you? Because the network is yours. It is a public resource that you, your businesses, the community and the government depend on. Since it is a communication channel that enables continuous global discourse, it is also essential for democracy. The Internet is now more essential to freedom of expression than any other medium. He brings to the networked age the principles that appear in the United States Constitution, the British Charter and other important documents: freedom from surveillance, filtering, censorship and disconnection.

Nevertheless, people seem to think that the Internet is like a part of nature and if it starts to deteriorate, then this is another one of those unfortunate events that we can't do anything about. But it is not true. We create the network by designing computer software and protocols, and this process is under our control. We choose which features it will have and which it won't. The internet is not defeated, and certainly not dead. If we want to know what the government is doing and what the companies are doing, to understand the true state of the planet, to find a cure for Alzheimer's - and even if we want to do something as simple as sharing our photos with friends - we the public, the scientific community and the media must ensure that the principles of the network are not compromised. Not only to preserve what we have already achieved but also to benefit from the great progress yet to come.

Universality is the basis

There are several important principles that will ensure that the value of the network will increase. The basis of its usefulness and growth is the principle of universality. When you link, you can link anything. This means that people can upload anything to the network regardless of the type of computer they have, the software they use, the language they speak and the type of connection they have, wired or wireless. The network should be accessible to people with disabilities. It should fit all types of information, a single document or data, a stupid "tweet" on Twitter or an academic document. It should also be accessible from any hardware capable of connecting to it: stationary or mobile, with a small or large screen.

These features may seem obvious, ones that don't require care or just unimportant, but they are the reason why both the new "hit" website and the home page of your child's soccer team will appear online without any difficulty. Universality is a meaningful requirement of any system.

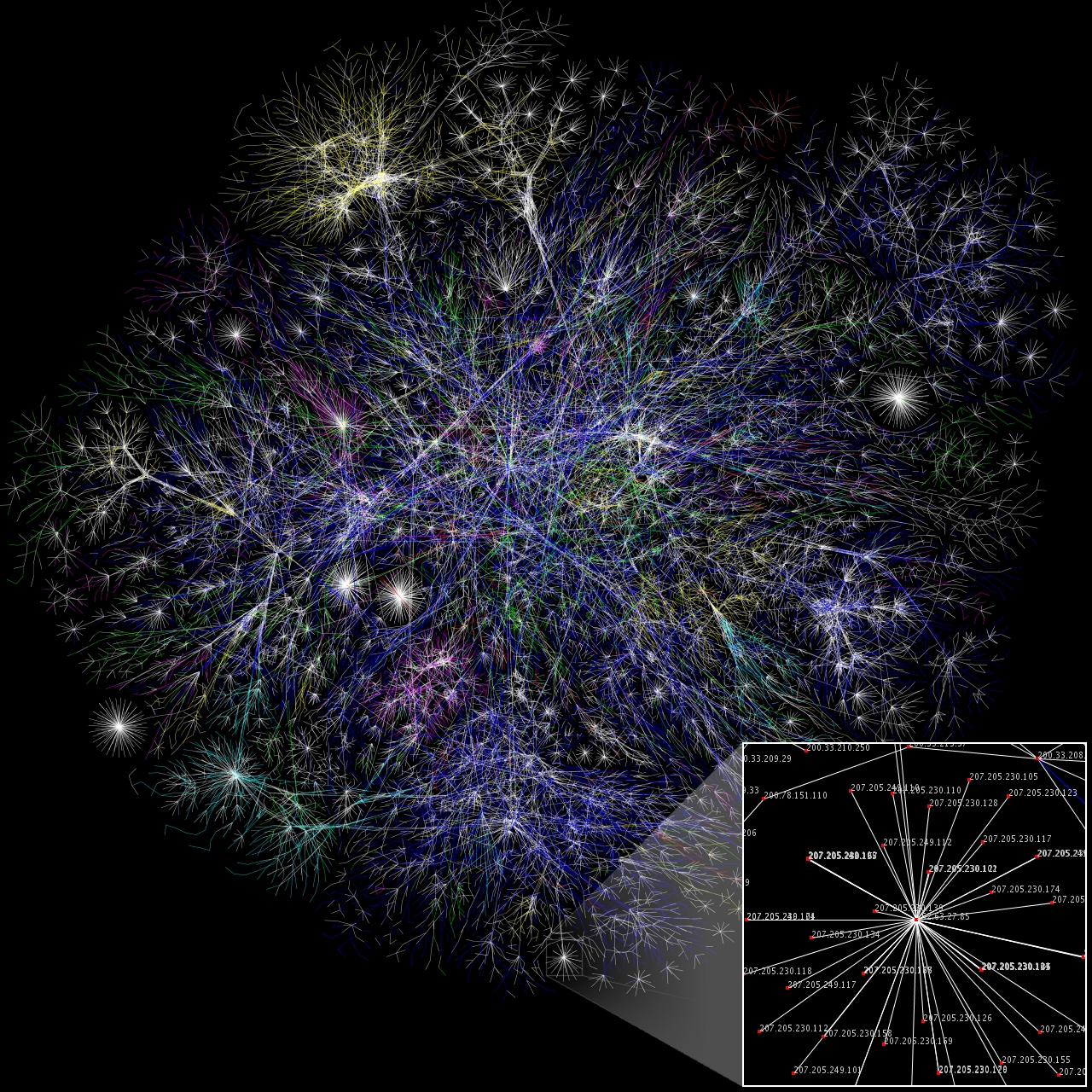

Decentralization is another important design feature. You do not need approval from any centralized authority to add a page or make a link. All you have to do is use three simple and standard protocols: write a page in HTML format (hypertext markup language), give it an address according to the address convention known as URI and upload it to the Internet using HTTP (hypertext transfer protocol). Decentralization has enabled extensive innovation and will continue to do so in the future.

The URI is the key to universality. It allows you to follow any link regardless of the content it leads to or the identity of the publisher of that content. The links turn the web content into something more valuable: a linked space of information.

Recently, several threats to the universality of the web have arisen. Cable TV companies that sell Internet access are considering restricting their Internet users to downloading only entertainment content on their behalf. Social networking sites are a different kind of problem. Facebook, LinkedIn, Friendster, and others typically provide value by collecting information you enter: your birthdays, email addresses, hobbies, and links that indicate who's a friend of whom and who's in which photo. The sites assemble amazing databases from these pieces of data and provide a value-added service based on this information - but only within the site. If you have entered data into one of these sites, you will not be able to easily use it on another site. Each such site is an isolated repository, cut off from the others. The website pages are indeed found online, but not the data. You can access the web page where the list of people you created on a particular site appears, but not send the list itself or parts of it to another site.

This quarantine is created because there is no URI for each individual piece of information. The links between the data exist only within the site. Therefore, the more you use it, the more trapped you are in it. Your social network site becomes a central platform - a closed repository of content, which does not give you full control over your information. The more this type of architecture becomes more common, the more the network breaks down and our ability to enjoy a single universal information space is impaired.

One of the dangers is that one social network site - or one search engine or one browser - will grow so large that it becomes a monopoly that limits innovation. Ever since the Internet appeared, continuous innovation in the field has created the best balance and check against companies or governments that have tried to undermine universality. Internet projects like GnuSocial and Diaspora allow anyone to create their own social network on their own server, and connect to anyone and any other site. The Status.net project, which operates sites such as identi.ca, allows you to run your own Twitter-like network without the centralization of Twitter.

Open standards drive innovation

The ability to create links from any site to any other site is essential to creating a strong network, but it is not enough. The basic network technologies that people and companies need to develop powerful services must be freely available royalty-free. Amazon.com, for example, became a huge online bookstore and later a music and general merchandise store because it had free and open access to the technical standards on which the network is based. Like any other user on the web, Amazon could use HTML, URI and HTTP without asking permission from anyone and without paying for the use. It could also use improvements to these standards, developed by the Network Consortium. These improvements allowed customers to fill out virtual order forms, pay online, rate the products they bought, and so on.

By the phrase "open standards" I mean standards that any expert may be involved in designing. These standards were tested by many people and were acceptable to them. Apart from that, the "open standards" are freely available on the web and users and developers are not required to pay anything for them. Open and easy-to-use royalty-free standards create the diverse wealth of web sites, from well-known sites such as Amazon, Wikipedia and Craigslist to remote blogs written by adults or home videos uploaded by young people to the web.

The openness also means that you can build a website for yourself or for your business without having to get permission from anyone. In the early days of the Internet, I didn't have to get permission or pay royalties to use the Internet's own open standards, such as the famous Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and Internet Protocol (IP). Similarly, under the Network Consortium's royalty-free patent policy, companies, universities, and individuals who contribute to the development of a standard must agree not to collect royalties from anyone who may use it.

Royalty-free open standards do not mean that a company or person is prohibited from developing a blog or file sharing software and charging money for their use. This is allowed, and you may want to pay for them if you think they are "better" than others. The idea is that open standards provide a choice of options, paid or free.

In fact, many companies invest money in the development of exceptional applications precisely because they are sure that the application can be used by anyone regardless of their computer hardware, their operating system or their Internet service provider - all thanks to the open standards of the network. This confidence encourages scientists to invest thousands of hours in developing databases to share information about proteins, for example, for the purpose of finding cures for diseases. This security also encourages governments, such as the US and UK governments, to publish more and more data online so that citizens can examine it, and the government becomes more transparent. Open standards also encourage creativity: someone might use them in ways no one imagined. We see things like this online every day.

The lack of open standards, on the other hand, results in the creation of closed worlds. Apple's iTunes system, for example, identifies songs and movies using open URIs, but instead of the prefix "http:" the address begins with "itunes:", which is a proprietary prefix protected by copyright. You can access the link that starts with "itunes:" only through Apple's proprietary iTunes software. You may not link to any information within iTunes, such as song or band information, for someone else to view. In fact, you are no longer online. The world of iTunes is a centralized and closed world. You are locked inside one store instead of being in the open market. This store may have great features, but its development is limited to the ingenuity of a single company.

Other companies also create closed worlds. The tendency of journals, for example, to create smartphone applications instead of web applications is a worrying trend because this content is found offline. It is impossible to save a bookmark for it, or send a link to the page by e-mail. It is impossible to "tweet" about him. It is better to build a web application that will also work in browsers on smartphones, and the techniques to do this are being perfected all the time.

Some believe that there is nothing wrong with closed worlds. They are easy to use, and seem to give people what they want. But as we saw in the 90s of the 20th century, when America Online's dial-up information system operated, giving users only a limited portion of the network, such closed and fortified "gardens", however pleasant they may be, will never be able to compete with the lively and bustling network market outside their gates In terms of versatility, wealth and innovation. However, when such a closed league has too strong a hold on the market, it may inhibit growth outside of it.

separate the network from the internet

Keeping a universal network and standards open helps people invent new services. A third principle - separation of layers - separates the planning of the network from the planning of the Internet.

This is a fundamental separation. The network is an application (application) running on the Internet, which is an electronic network that transmits information packets between millions of computers according to several open protocols. The network can be compared to a household electrical appliance, which operates thanks to the electrical infrastructure. A refrigerator or printer is able to operate as long as it uses some standard protocols - for example, 220 volts and alternating current at a frequency of 50 Hz. In the same way, any application - such as the network, e-mail and instant messages - can operate on the Internet as long as it uses some standard protocols, such as TCP and IP.

The manufacturers can improve refrigerators and printers without changing the way the electricity network works, while the infrastructure companies can improve the electricity network without changing the way the devices work. The two layers of technology work together, but can progress separately. The same is true for the network and the Internet. The separation of the layers is essential for innovation. In 1990, the network was deployed across the Internet without any changes to the Internet itself, as happened with all the improvements achieved since then. At the same time, the speed of the Internet connection was accelerated from 300 bits per second to 300 million bits per second (Mbps) without having to redesign the network to benefit from the upgrade.

Electronic human rights

Although the Internet and the network are designed separately, network users also use the Internet, so they rely on interference-free Internet. In the early days of the Internet, companies and countries had difficulty intervening in the Internet to interfere with a single user of the Internet. Since then the intervention technology has been getting more and more sophisticated. BitTorrent, whose peer-to-peer network protocol allowed people to share music, movies and other files over the network, complained in 2007 to the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that Internet service giant Comcast blocked or slowed traffic to subscribers who used BitTorrent. The commission ordered Comcast to stop, but in April 2010 a federal court ruled that the commission could not compel Comcast to do so. A good ISP will usually manage traffic so that when bandwidth is limited less important traffic is slowed down. But this is done transparently, and users are aware of the slowdown. An important line is drawn between such an action and using this power to abort.

This distinction emphasizes the principle of net neutrality. The meaning of the principle is that if I paid for a connection to the network of a certain quality, let's say at a rate of 300 megabits per second, and my neighbor also paid for a connection of the same quality, our connection to the network will indeed be of this quality. Protecting this idea would prevent a major ISP from streaming video from a media company it owns at 300 megabits per second, and streaming video from a competing company at a slower rate. Such activity is commercial discrimination. There may be further complications: what if the provider makes it easy for you to connect to a certain online shoe store and makes it difficult to access others? This is a fairly large control. And what if the provider makes it difficult for you to surf the web sites of certain parties or religions or sites dealing with the theory of evolution?

Unfortunately, in August 2010, for some unknown reason, Google and Verizon argued that net neutrality should not apply to mobile phone connections to the network. Many people in rural areas, from Utah to Uganda, can access the Internet only through mobile phones. Excluding wireless from net neutrality would expose these users to service discrimination. It is strange to imagine that the right to access any source of information at will applies when surfing on a computer via the wireless home network, but not when using the cell phone.

A neutral intermediary for the media is the basis for a fair and competitive market economy, for democracy and for science. In the last year, the debate arose again on the question of whether government legislation is necessary to protect net neutrality. There is indeed a need. While the Internet and the web often thrive in the absence of oversight, some basic values must be preserved in law.

without prying

Other threats to the network arise from internet interference, including eavesdropping. In 2008, a company called Phorm developed a method by which an Internet service provider can peek into the packets of information it transmits. This way he can identify every URI that his customers visit, and create a profile of sites that each customer visits based on this information to enable targeted advertising.

Accessing the information inside an internet package is similar to wiretapping a phone or opening a mail envelope. The URIs people use reveal many things about them. A company that buys URI profiles of job applicants could use them to discriminate against, for example, people with certain political views. Life insurance companies will be able to discriminate against people who searched the Internet for information about symptoms of heart disease. Attackers can use profiles to track victims. We would all use the web in a completely different way if we knew that our clicks were being monitored and that the information was being transferred to a third party.

Freedom of speech must also be protected. The web should be like a smooth sheet of paper: ready to be written, without any control over what will be written. Last year, Google accused the Chinese government of hacking into its databases to extract e-mails from regime opponents. These alleged hacks occurred after Google resisted the Chinese government's demand to censor certain documents on its Chinese-language search engine.

Totalitarian governments are not the only ones who violate the internet rights of their citizens. A 2009 French law, known as Hadopi, allowed a new agency by that name to cut a household off the grid for a year if a media company claimed someone in the household had pirated music or video. Following strong opposition to the law, the French Constitutional Council demanded in October 2010 that a judge review the case before denying access to the network, but determined that if he approved it, it would be possible to disconnect the household without legal proceedings. The Digital Economy Act hastily enacted in England in April 2010 allows the government to order an Internet service provider to terminate the connection to the network of any person who appears on a list of suspects of copyright infringement. In September 2010, the US Senate introduced the Anti-Copyright Infringement and Online Counterfeiting Act, which allows the government to create a blacklist of websites accused of copyright infringement, whether hosted in the US or abroad, and to pressure all Internet service providers to block access these sites or instruct them to do so.

These laws do not allow the existence of a legal procedure that protects people before they are disconnected or their website is blocked. Considering the essentiality of the web to our lives and work, such disconnection is a form of denial of freedom. If we look at the wording of the Magna Carta, perhaps we should now say: "The ability to connect with others shall not be denied to any person or organization without due legal process and a presumption of innocence."

When your network rights are violated, there is a vital need for public protest. Citizens around the world expressed strong opposition to China's demands from Google, so Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that the US government supports Google's refusal and that internet blackness - as well as network freedom - should be an official line in US foreign policy. In October 2010, Finland established that broadband access at a speed of 1 megabit per second is a legal right of all its citizens.

Links to the future

As long as the basic principles of the network are preserved, its continued development will not be in the hands of a single person or organization - mine or anyone else's. If we can preserve these principles, we will enjoy the fantastic future capabilities that the web holds.

The latest version of HTML, for example, called HTML 5, is not just a markup language but a computing platform that will make web applications more powerful. The expansion of the use of smartphones will make the network more central in our lives. The wireless access will be a real treasure for developing countries, where many people do not have a wired connection but have a wireless connection. Of course, there are many more things to do, including improving accessibility for those with disabilities and creating pages that will work well on any screen, from huge wall-sized XNUMXD displays to wristwatch-sized windows.

A great example of future proofing that leverages the benefits of all the principles is the use of linked data. Today's web is quite efficient for people posting and searching for documents, but our computer programs are unable to read or modify the data within these documents. With the solution of this problem, the network will become much more useful because data describing almost every aspect of our lives is created at an incredible rate. Hidden within this data is knowledge about curing diseases, improving business value and managing our world more efficiently.

Scientists are at the cutting edge of trying to put linked data online. For example, researchers realize that in many cases a single laboratory or online database is not enough to discover a new drug. The information needed to understand the complex interactions between diseases, biological processes in the human body, and the vast variety of chemical substances is scattered around the world in masses of databases, spreadsheets, and documents.

One success story is related to the discovery of a drug to fight Alzheimer's. Some commercial and government laboratories stopped refusing, as a rule, to open the data and created the Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative. They put a huge amount of linked data on patients and brain scans online and "dived" into them many times to advance the research. In the demonstration I predicted, a scientist asked: "Which proteins are involved in signal transmission and are associated with the pyramidal neurons?" A Google search for an answer brought up 233,000 results - and not a single answer. In the world of linked databases, however, some specific proteins with these properties have emerged.

Even in the field of investments and finance it is possible to benefit from linked data. Profit is often generated by spotting patterns in an ever-expanding collection of data sources. Our daily lives are also full of data. When you enter a social network site and indicate that some participant is your friend, this creates a relationship - and such a relationship is a given.

Linked data creates some problems that we will have to deal with in the future. For example, the new capabilities to combine information may pose privacy challenges that are almost entirely unaddressed by today's privacy laws. We must examine legal, cultural and technical options for maintaining privacy without harming the capabilities useful for sharing data.

These are exciting times. Network developers, companies, governments and citizens need to work together openly and cooperatively, as we have done so far, to preserve the fundamental principles of the network and the Internet, and to ensure that the technological protocols and social conventions we create respect basic human values. The purpose of the network is to serve humanity. We're building it now so that its future users can create things we can't even imagine.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About the author

Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web (www). Today he manages the international World Wide Web Consortium, which is based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the United States. Berners-Lee is a professor of engineering at MIT and a professor of electronics and computer science at the University of Southampton in England.

in brief

The principle of universality allows the network to operate independently of hardware, software, network connection or language, and handle information of all types and quality levels. This principle guides the design of network technology.

Open and royalty-free technical standards allow people to create applications without asking anyone's permission or paying. Patents and web services that do not use the URI limit innovation.

Threats to the Internet, such as companies or governments interfering with or eavesdropping on Internet traffic, endanger people's basic network rights.

Web applications, linked data, and other future network technologies will only thrive if we protect the fundamental principles of this medium.

How It Works

Network or Internet?

The network is an application on the Internet. So are instant messages. The Internet is an electronic network that divides the information coming from different applications into packets and sends them through cables and wireless connections between computers, according to simple protocols (rules), known by various acronyms. On the Internet and in applications, you can see layers that are placed on top of each other: each layer uses the services of the layer below it. The applications can be compared to household appliances, which connect to the electrical infrastructure in a standard way.

Looking ahead

The future network in action

Some exciting emerging trends, based on the core principles of the web, may change the way the online and physical worlds operate. Notes and visual illustrations of these four trends appear in the links in the box at the end of the article.

open data

Uploading data to the network and linking them create new and dynamic capabilities for people everywhere. It has already helped cyclists in London avoid accidents, exposed discrimination in Ohio and helped rescue teams help people in Haiti after the great earthquake in January 2010.

Network Science

We have only begun to scratch the surface when it comes to understanding how the web reflects and shapes the real world. Many institutions are engaged in the new research field of network science, which provides intriguing insights into the design of the network, its operation and its impact on society.

social engines

Many people publish reviews and ratings of restaurants, and this affects the choices of those who want to eat at the restaurant. This activity is an example of a social engine. More complex social engines are now being designed, which could improve scientific research and democratic governance.

Free bandwidth

Only a few people in developing countries can afford access to the Internet. Free service with very narrow bandwidth could greatly improve education, health and the economy in these areas, as well as encourage people to upgrade to faster, paid service.

For more information

Creating a Science of the Web. Tim Berners-Lee et al. in Science, Vol. 313; August 11, 2006.

Network Science Research Initiative website: www.webscience.org

Posts by Tim Berners-Lee on network planning and other topics:www.w3.org/DesignIssues

The main page of the World Wide Web Consortium:www.w3.org

The Foundation for the Worldwide Network finances and coordinates the operations to ensure the network's service to humanity: www.webfoundation.org

More on the future of the network: www.ScientificAmerican.com/dec2010/berners-lee

Link to image In accordance with the CC license

5 תגובות

and in this regard -

The new generation of IP protocol is called IPv6

It will also allow the "little surfers" a real connection to the Internet, one that does not hide behind me

other IP addresses, and allows the installation of any server and any application at home.

Free internet is even more essential to society than a cottage...

And worth fighting for.

point

Because of your stupidity, you didn't notice that you had all the freedom to write the stupid comment you wrote.

Say, do you like to provoke or are you just a tick?

I actually enjoy the social network, as a center for content from people and institutions that interest me.

Such an important article.

Thanks.

Google is already hiding information from us

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8ofWFx525s

Social networks promote human stupidity and certainly not freedom