How does the brain create traumatic memories, and can these memories be "disappeared"? Scientists from the Weizmann Institute discovered that when the connection between the nerve cells in the amygdala and the cerebral cortex in the brains of mice was weakened, traumatic memories were "erased" in them, and they stopped reacting with panic to fear-inducing stimuli.

Erasing unwanted memories is, still, a science fiction idea. But scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science recently succeeded in "disappearing" traumatic memories from the minds of mice. As part of the new study, QPublished today in the scientific journal Nature Neuroscience, the scientists eliminated the brain mechanism by which the fear memory is produced in mice. As a result, the mice stopped reacting with panic to the event that was supposed to provoke this reaction in them. This research may help in the understanding of the mechanisms by which traumatic memories are created in humans; For example, among people suffering from post-traumatic syndrome.

"The brain excels at creating memories associated with a powerful emotional experience, such as great pleasure or great fear," says Dr. Ofer Yizhar, who heads the research group. "That's why it's easier for us to remember things we care about, whether they are positive or negative events. But this is also the reason why traumatic events are kept in the memory for a long time. This tendency prepares the ground for post-traumatic syndrome".

The members of Dr. Yizhar's group in the Department of Neurobiology - the postdoctoral researchers Dr. Oded Kluyer (now a faculty member at the University of Haifa) and Dr. Mathias Friga - together with Prof. Roni Paz and the student Ayelet Sharel (also members of the department), studied the interactions between two areas of the brain: the amygdala and the frontal cortex. The amygdala plays a central role in the control of emotions, while the frontal cortex is mainly responsible for cognitive activity and the storage of long-term memories. "Past studies have taught that the interactions between these two brain areas contribute to the creation and storage of negative memories," explains Dr. Yizhar. "They also suggested that these interactions go wrong in people suffering from post-traumatic syndrome, but until today it was not known what mechanisms were involved."

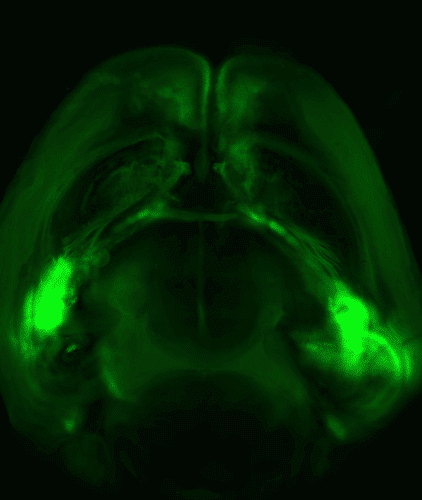

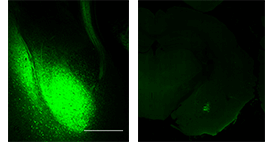

As part of the new study, the scientists used a genetically modified virus, and thus marked the nerve cells in the amygdala that communicate with the frontal cortex. Then, using another virus, they injected into these nerve cells a gene that codes for a light-sensitive protein. And so, when they "illuminated" the brain, they activated only nerve cells containing the light-sensitive protein. These research methods, called "optogenetics", are studied in depth in Dr. Yizhar's laboratory. "Optogenetics allowed us to activate only the neurons in the amygdala that communicate with the cerebral cortex, and thus we were able to map in the cerebral cortex the cells that receive signals from the light-sensitive neurons," explains Dr. Yizhar.

"The brain excels at creating memories associated with a powerful emotional experience, such as great pleasure or great fear. Therefore, it is easier for us to remember things we care about, whether they are positive or negative events. But this is also the reason why traumatic events are kept in the memory for a long time"

After being able to precisely control the communication mechanism between the cells, the scientists turned to studying the behavior of the mice. They discovered that when the mice were exposed to a fearful stimulus, a powerful "communication channel" was activated in their brains, linking the amygdala and the cerebral cortex. It also became clear that the mice in whose brains this communication channel was activated tended to "preserve" the memory of fear: the mice reacted with panic every time the sound that previously accompanied the frightening stimulus was heard.

To find out how this channel contributes to the creation of memories and their consolidation, the scientists developed an innovative optogenetic method, designed to weaken the connection between the amygdala and the cerebral cortex. This method is based on series of repeated flashes of light. "After we weakened the connection between the amygdala and the cerebral cortex, the mice were not frightened at all when we played them the 'scary' sound," says Dr. Yizhar. "Apparently, without the information flowing from the amygdala to the cerebral cortex, the fear memories were undermined, or even disappeared completely."

In fact, explains Dr. Yizhar, the researchers focused on a basic research question: how the brain combines emotion and memory. "It is possible that one day, we will be able to develop drugs that will affect the connection between the amygdala and the frontal cortex," he says, "and thus we may be able to relieve people suffering from a wide variety of syndromes related to anxiety and traumatic memories."

3 תגובות

Thank you! Excellent article!

A very interesting article raised a lot of questions and curiosity and yet there is a great fear of the interference of science in what should be completely natural..

Great article