A map represents for us the closest description of reality. Ancient maps were created to place man within the world and later to move within it. The realization that the natural environment can be marked with symbols was one of the biggest revolutions in human history

Almost 17 thousand years ago, in the southwest of France, one of our ancestors lay down at night, looked at the infinity of stars above him and decided to try and draw what his eyes saw.

The result was one of the first maps known to us, a map depicting the surface of the sky, the "roof of the world" as the painter saw it from above. The map was discovered on the walls of the famous Lesko cave along with other nature paintings where the same ancestor lived and worked.

Drawing the surface of the sky is not a particularly complicated task. It is a flat two-dimensional space, where light points stand out and are easy to copy and code. The importance is in the act of copying - additional paintings in the cave indicate that this is a group of people who managed to connect the reality around them with the symbols of reality that they created themselves.

The map of the sky was not created for use, but as a perception of a person operating within an environment, in fact within a universe and identifying himself as a part of it. The map placed man in a new context of space, nature and symbol.

Cartography - a matter of geography

Most of the maps of the ancient world were not created as useful tools. One of the oldest world maps found is a Babylonian map from the 7th century BC. The map depicts a scheme of the world in the eyes of the Babylonians. It consists of two circles of water ("sweet" - rivers, and "bitter" - the ocean), within which are countries. In the center stands the city of Babylon, which occupies about a quarter of the surface of the "world".

The main reason for drawing such a world map is to show the relationship between the culture that created the map and the rest of the world. The Babylonian map includes, for example, a description of neighboring countries - Armenia, Ethiopia, Assyria, but elegantly ignores the existence of the Egyptians and the Persians, countries that undoubtedly were known to the Babylonians but they did not want to refer to them.

The similarity between the Babylonian map and medieval European maps is amazing. The map of the world according to Europe of the Middle Ages was called the TO map and also in it the world is presented as a circle centered on Jerusalem which is divided by bodies of water in the shape of a T. Asia stands in the north and Europe and Africa in the southeast and southwest, respectively.

The European interest in the world was schematic, philosophical and moral - a graphic presentation of Jerusalem, the place of Christ's crucifixion in the center, then a division according to the Christian faith, between the people of Shem (Asia), Ham (Africa) and Japheth (Europe). On a practical level, medieval Europe was a self-interested culture. The real world didn't interest her.

The ancient maps do not depict the world as it is, but as the people of the time understand it or want it to be seen. The maps are a kind of world view, they describe the countries and the people in relation to others. This is how a center, borders and even a kind of subjective scale are determined for the map.

Later cartography always maneuvered between two needs: the primary and ancient need to locate and understand the world, alongside the more modern, pragmatic need - the ability to navigate in space. The first need is almost philosophical. The second need is practical, and in modern terms it served as an economic and social growth engine.

Do you even need maps?

In the practical aspect, maps are first and foremost for navigation, but even today, as in the past, the importance of accurate maps for navigation is only secondary. Take for example someone who leaves his house for work. Does he need a map to get there? definitely not.

He knows that if he walks down the street, turns left, continues a few hundred meters, takes a bus and gets off at the third stop - he will reach his workplace. It is not necessary to understand the terrain image to reach the destination.

The London Underground map is one of the most famous maps in the world. She stars on t-shirts and postcards - a graphic icon that symbolizes an entire city. It's also an incredibly useful map - a new passenger will be able to navigate the London Underground in minutes. And yet, there is almost no connection between the map, created by Harry Beck in 1931, and the geographical reality of London.

The subway map is another link in a series of schematic aids, which have been the bread and butter of navigation for thousands of years. Unlike maps that describe the wider world, they function mainly as a series of traffic instructions - to get to Marble Arch from Charing Cross station, ride the brown line for two stops, then get off and get on the red line for two more stops. magic.

In the pre-modern world, navigational information was not stored on maps. The ship's navigator together with the captain had navigation books in which the knowledge recorded by previous sailors was accumulated. Greek, Roman and Phoenician sailors navigated using the periplus (περίπλους), a "sailing around" which was a travel guidebook.

Schematic maps, far from an accurate geographical description, were significant navigational tools at sea and on land, long after the fall of the Roman Empire. The periplus developed into the portolan maps - a description of landmarks on the coastlines along which European ships navigated. The Romans used similar methods on land.

Maps created later By the al-Balki school, which originates from the Abbasid caliphate, a collection of points connected by straight lines or at 45 degree angles are indicated, which ignore the terrain route or the real distance, but provide the traveler with basic instructions and an effective navigation option.

discover the nature of the world

As mentioned, the philosophical need was a significant driver in the development of cartography. It is no wonder that the mapping of the world advanced in ancient Greece at the same time as the development of philosophy. An important mapping project was carried out by the Catius of Miletus, a historian and geographer of the fifth and sixth centuries BC, who combined the personal knowledge he gained during his travels in the Mediterranean Sea with an earlier map published by his fellow citizen, Anaximander.

He created one of the first (Eurocentric) world maps. The maps of Catius and his pre-Socratic contemporaries were circular, since they assumed that the world was round and flat like the top of a column. Maps do not have a standard scale or measure of distance. The distance between the cities was specified in a number of walking days.

Already in Aristotle's time, at the end of the fourth century BC, they knew that the shape of the world was spherical, but the great significant breakthrough was made when it was possible to calculate the circumference of the sphere and therefore also estimate its size.

The Greek mathematician Artosthenes was the first to be able to perform the calculation by measuring the angle of the sun at two points in Egypt. He discovered by measuring that the distance between Alexandria and Aswan is 1/50 of the circumference of the earth, so according to his calculations the circumference of the sphere was equal to 46,250 kilometers, about 15 percent more than the real circumference.

Ptolemy's revolution

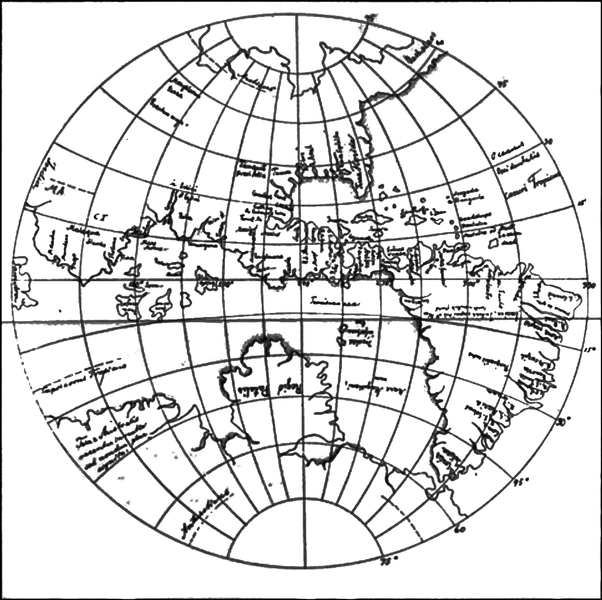

The greatest revolution was made by the Greek astronomer, geographer and scientist Ptolemy (of the second century AD), whose maps he drew shaped the geographical perception of the West and the Islamic world for 1,300 years, and were actually used by Europe until the time of Columbus.

Until Ptolemy, the maps were drawn from the general to the particular: the cartographer had a perception of what the world looked like or what a certain area of it looked like, and he put it on the map and inserted details into it as he saw it or knew.

Ptolemy worked in the opposite and revolutionary way - mapping from the individual to the general. Ptolemy's map was based on a grid of coordinates consisting of lines of latitude and longitude. The image of the world was built from the foundation to the tefahot, in small pieces, instead of trying to sail and guess the general shape of the world. According to Ptolemy's approach, if there was no knowledge of a certain area, it should not be placed on the map.

| The map of the 21st century | ||||||

|

With the collapse of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Middle Ages, the development of cartography in Europe stopped. Much knowledge was lost, including Ptolemy's "geography". The Muslim world, on the other hand, continued to be interested in the world and develop mapping methods.

The European rediscovery of Ptolemy's work was nothing less than a revolution. The first copy reached the West from Constantinople in the late 14th century, and a version translated into Latin (which did not contain maps), was published in 1406. Subsequently, editions were circulated that reproduced Ptolemy's maps and his method. Europe began to understand the world anew and marched towards a new era.

One of the first copies of Ptolemy's Geography was purchased and avidly read by a Junovesian sailor named Columbus. In the 15th century, ambitious sailors were constantly looking for better trade routes and eagerly read geographical texts they found.

Ptolemy made Columbus believe that traveling west to reach the east was possible. Ptolemy was wrong about the size of the world: he estimated the circumference of the world to be one-sixth smaller than its actual size, a mistake that encouraged Columbus to embark on a voyage around the world.

Map and reality

The medieval man who looked at the TO maps knew that the map did not represent the world "really", as he knew that people do not look in reality as they are drawn on the tapestries that were decorated in the noble castles at that time. However, modern maps had the pretense of representing reality "as it is".

As the accuracy of maps grew, the greater real value was given to them. If we show someone a map of Israel today and ask them what it is, the first thing most people will say is "Israel", not "a map of the Land of Israel". We understand that there is a gap between the signifier and the signified, but due to the high truth value we attribute to the map, we begin to mix them up.

One of the main problems that prevented attributing a real value to maps is the difficulty of transferring to a flat map the surface of a round sphere. The problem was partially solved by using "the levy", a mathematical way to translate the surface of the sphere into a two-dimensional map.

In 1569, a Flemish cartographer named Mercator defined "Hitel Mercator". This projection, in which the Earth's course is superimposed on a cylinder that "wraps" it, was particularly useful to sailors due to its ability to show a consistently straight course.

The problem with the Mercator projection was its tendency to distort large bodies. Bodies near the equator were shown as smaller than they are, so for example Africa became very small while America and Northern Europe were very large. The size of the distortion was significant: Greenland, for example, appeared almost the same size as Africa, when in reality the area of Africa is almost 14 times larger than that of Greenland.

If in the past there was a separation between useful maps and world maps, from the moment that cartography allowed a combination of the two, the maps took on a true value. Postmodernist cultural critics may cluck their tongues and argue that there is something very comfortable about the white Western hegemony that has presented Africa in miniature.

Tal Gutman is a high-tech enthusiast historian who writes about analog culture and digital history.

His blog:www.eliam.org

3 תגובות

I want to study for a geography exam,

And I had no way to learn {write questions and formulate in a different way}

{I'm in the 2th grade, time flies!!!!!!

Just correcting the blog address - http://www.eilam.org

interesting article,

I think it is worth emphasizing that there is no difficulty in transferring a round space to a flat map, but that it is simply impossible.

All the levies of any kind actually select the segment of the KDA where we are interested in reducing the distortion and yet, any flat map of the KDA or part of it will always include distortions.