Chapter 9 in the book of Robin Merenz Hennig - The Monk in the Garden, the story of Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics. The chapter discusses the question of what would have happened if Darwin had been aware of Mendel's theory of heredity

Robin Merenz Hennig

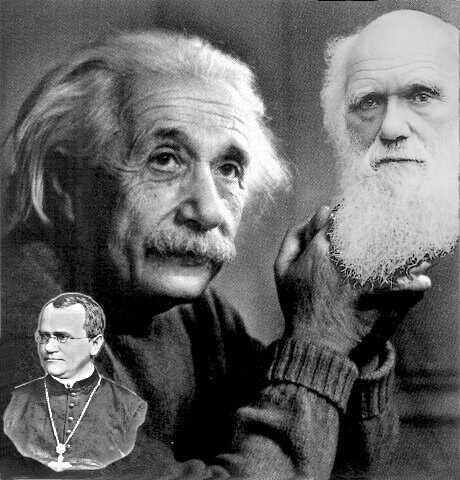

Photomontage of Darwin, Einstein and Mendel

The possibility of change lies in the constant magic of the garden.

Alluring images always shine from past experience

and colorfulness of the future.

– The Garden from Month to Month, Michael Cabot Sedgwick

The mood of the crowd that had gathered in the library was clouding from moment to moment. About seven hundred people gathered in the long western hall, after they had tried to squeeze into the lecture hall, and with this excitement overflowing, they crowded there. And even this hall was too small to accommodate everyone, so they moved to the library. There were scientists, theologians, scholars from Oxford and their students. And even women - those "glorified matrons and maidens" that at least one of the scientists, the revered Adam Sedgwick from Cambridge, sought to shield them from the horrors of evolutionary thinking. The clergy concentrated in the middle of the hall, the students - in the northwest corner. Apart from the latter, most of those present in the hall were staunch opponents of Darwin.

It was on June 30, 1860, in the middle of the annual conference of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, which lasted for a week. This year the organization met in Oxford, and on this day a discussion was opened on the most controversial issue that was on the agenda: Darwin's theory of natural selection.

Darwin published his ideas only seven months before, on November 24, 1859. The Origin of Species, which took twenty years to prepare, created an overnight sensation. The first edition. 1,250 copies in total, sold out of bookstores on the day of its appearance. A second edition appeared a month later, the day after Christmas. Six editions of the Origin of Species were eventually published in Darwin's lifetime; Starting with the fourth, the author introduced considerable changes in his book, which diluted some of his most extreme heretical beliefs in order to include more of the Anglican Church's palate, the dominant orthodoxy in biology. and his devoted wife Emma.

Darwin, who in his youth intended to be a priest, never understood why his theories provoked such outrage, why they caused him to be denounced as anti-religious. "I see no real reason why the views presented in this volume," he wrote in Origin of Species, perhaps hoping to calm the storm before it erupted, "should shock the religious feelings of any person."

But they shocked the feelings of many. And it seems that those with the strongest views gathered in that hot library on the last day of the month of June, to witness a debate that was expected in advance to stir up the spirits.

At the head of the supporters stands, as always, Tomom Henry Huxley. An anatomist and paleontologist who bought his education on his own. Darwin himself had no interest in defending his theory. He was reluctant for a confrontation, and he did not have the necessary energy. Writing the Origin of Species, a 400-page "summary" that was finally completed in fifteen months of frantic labor, exhausted Darwin - who was chronically disabled most of his life. To such an extent that he was forced to retire to a convalescent holiday in Ilkley immediately after the book was published.

He turned to his great friend Huxley, a member of one of the most illustrious families in England, and gladly entrusted him with the defense of his views. But when Huxley was asked to teach a defense of Darwin at the British Association conference, he was urged to answer in the negative. The Agora, the cousin of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, was the most respected scientific organization in Israel, and it convened an impressive group of experts to discuss the issue. Against Darwin will stand the hegemon Samuel Wilberforce, known by his nickname "Sam the Sovan" - a man and a man. Pleasant-mannered and witty, who was known as a persuasive speaker even though he was not gifted with extraordinary intellect. Huxley was not particularly eager, as he put it, to absorb "hegemonic blows".

In the end, a common friend of Darwin and Huxley came, Robert Chamberm - a well-known essayist. A nature lover and author of the Chambers encyclopedia - and imposed a mountain on him as a tub. But strong on Huxley who came back and regretted his willingness to stand up to the burst, immediately realizing how difficult this crowd would be. For one terrible sequence of nine straight minutes the crowd silenced three speakers one after the other. "Suppose this point marked by A is a man, and this point marked by B is a monkey," said the last victim, Henry Draper. Unfortunately, he spent twenty-eight years in America, and acquired an accent that the audience called Hokkah and Atalula. Unfortunately for him, he said "cauf" instead of "monkey."

"Ka-off! Ka-off!” roared the crowd, sending Draper in disgrace and demanding to hear the hegemon. Then the clever Sam stood up and spoke - he didn't even know exactly what Darwin's views were, but he spoke sarcastically, and posed one poignant question to Hexley that will never be forgotten.

"Tell me, my lord," the hegemon asked to know, "are you descended from a monkey on your grandfather's side or on your grandmother's side?"

Huxley's answer is not known with vigorous precision, because he and others later tried to embellish what was actually said. Among the more colorful descriptions given at the time. Since the nickname received extensive coverage in popular weeklies such as Athenaeum or Macmillan's - there were some who put a stinging answer in Huxley's mouth, so much so that the audience went out of their way and one woman fainted. In a letter to a friend, Huxley described his answer as annoying and dreary: "I would have preferred my grandfather to be a miserable monkey, and not a man whom nature has blessed as good, who has multiple means and power of influence at his disposal, and yet he uses these virtues and this influence for the despicable purpose of introducing ridicule into a serious scientific discussion .”

But other descriptions put in his mouth a much more striking answer, and it is the one that is engraved in the memory: "It's better for me." By definition, it is better for me, sir, to be the offspring of a monkey and not of a ruler."

Could Darwin have been surprised that his book caused such a wild outburst? He knew, of course, that he was challenging man's status as the beloved of God, who was created in his image and likeness. That is why it took twenty years to write the book, to carefully gather fact after fact to strengthen his claim. What motivated him to publish the things in the end was the discovery that one of his competitors was going to precede him and go to print with an almost identical idea. Twenty years after the Origin of Species appeared. He was still denounced by the religious establishment. Calling Darwin's idea a "hypothesis," wrote one of the churchmen, "gives him an honor he does not deserve. A pile of garbage is not a palace, and a pile of nonsense is not a hypothesis."

Even among those who finally came to terms with the idea of "transmutation" - this word usually stood where "evolution" stands today - a serious disagreement emerged on the question of whether species change gradually or suddenly, on the question of how adaptive traits are passed from one generation to the next: and on the question of what exactly is its role of natural selection and what is the nature of its mechanism.

This debate, which was still going on in the twentieth century, provided the background for the integration of Mendel's article into the theories that were taking shape about evolution and about genetics. Developments in cell biology in the eighties and nineties of the nineteenth century paved the way for the understanding of Mendel's theories about the discrete factors responsible for heredity and the renewed interest in Mendel's ideas paved the way for the understanding of Darwin's theories about the mechanisms of "descent with modifications". Until then, no one had been able to understand how natural selection worked - not even Darwin himself.

From the moment it was published, The Origin of Species caused much grief to biologists, theologians and laymen who believed that the Book of Genesis is the words of a living God, and that each and every word in it should be understood simply. The greatest distress of all was probably caused by the successors of John Lightfoot, a seventeenth-century scholar who was vice-governor of Cambridge University. Hela stated that he knows exactly when creation took place, and is able to determine at what moment the first Adam appeared: nine o'clock in the morning on Sunday, October 23, 4004 BC.

The development of Darwin's two-part theory, which comes to explain transmutation - the "war of existence" at the foundation of things and the pair of driving forces, "random variation" and "natural selection" - illustrates in itself the nature of evolution, as an accumulation of small changes over a long period of time. It is possible to place the first Betzvotsia about thirty years before, in 1831, when the young Darwin sailed on a small cold ship of the Royal Navy, the Beagle, as a guest at the captain's table.

Captain Robert Fitzroy fears that he will suffer from loneliness and boredom during such a long journey to the coast of South America and back. The conventions of Victorian society forbade the captain from associating with his crew - not even with the doctors, draftsmen and engineers among the ship's professionals. Fitzroy was anxious about five years of feasting in solitude, and feared their effects on his mental health. Beagle's previous captain, Pringle Stokes, had shot himself three years earlier during a similar voyage: the burden of loneliness was too much for him to bear. And Fitzroy knew that he had an innate tendency to lose his sanity. Among his ancestors, a long line of aristocrats who traced their origin directly to King Charles II, were mentally ill and suicidal, including his uncle, Viscount Castlereagh, who slit his own throat in 1822.

That's how Darwin came into the picture. He was the perfect companion, a young man of the upper class whose interest in the study of nature helped him recognize the allure of sailing to Patagonia. The two were almost the same age "only a year separated them - and got along well on land; That's why Darwin joined the cruise, for the adventure involved. But Fitzroy's personality changed from end to end from the moment the sails were first set, and at sea his authority was complete, final and absolute.

Fitzroy proved to be an intolerable man. He spoke at length every evening in the evening, and Darwin, who was after all a paid interlocutor, had no choice but to listen. All the animals on earth, Fitzroy declared, and even the hitherto unknown birds and turtles found in the islands off the coast of South America, were created directly by the Creator. And the proof of God's sublime plan, of his love for us and of the fact that we are a species destined for greatness, is found in the supremacy of the Tory party in the British Parliament - an argument that Darwin, loyal to the Whig party, resented most of all.

How could he bear such five long years? When Darwin ended Fitzroy's monologues, he gave his opinion on the rare opportunity that had come before him as a budding naturalist. The sailing plan set for the ship - to the Pacific coast of South America, through Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, and from there to Chile and Peru and even to some nearby islands, such as the Galapagos - will help Darwin to accumulate new collections of exotic exhibits from the other side of the world, exhibits that would never have come into his hands in any other way. Indeed, so great was his enthusiasm for collecting that within a few months he was pushing the ship's official naturalist, Robert McCormick. Since Hella was unable to keep up with the pace dictated by Darwin - who came to the ship with a servant, with private capital and with all the enthusiasm of the amateur - and since he had an additional role as the ship's doctor, McCormick did not have at his disposal the leisure available to Darwin, to go ashore at any berth, hire The services of some locals eager to help, and go hunting are introduced.

Nor did he enjoy the advantage that Darwin had in his evening conversations with the captain. which were in this context an important source of strength. In April 1862, after only half a year on the waves, McCormick was fired; He had to ask for a free ride home on Her Majesty's ship Tyne.

At the beginning of his career, Darwin believed with complete faith in the permanence of species, but he was well aware of the competing theory, transmutation: the ability of species to change, and the disappearance of species from the picture. Among other things, he became familiar with transmutation thanks to the writings of his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, who passed away before Charles was born, but his book Zoonomy, The Laws of Organic Life was an inseparable part of the family tradition, and family members discussed it extensively. Erasmus Darwin was a lively man, chasing dresses to the point of scandal, who even wrote down some of his ideas in the study of nature in the form of erotic poetry, such as his poem for the classic "The Botanical Garden" (1794). Erasmus Darwin, a devout Christian, believed that changes are the fruit of God's plan and usually lead to the improvement of species over time. But he also believed in the existence of three forces driving transmutation: hunger, the need for security, and the lust for flesh.

After Beagle returned to England in October 1836, Darwin rented a residence in London and began to ponder speciation. Mendel was still a boy in Heizendorf, attending a high school twenty long miles from his home, composing poetry about medieval inventors and dreaming of immortality. During the next two years, while Mendel continues his studies at the gymnasium, which is even further away from his home. Darwin gradually accepted the belief in transmutation.

From 1836- to 1838 he read from the next to the next. He dipped his toe in geology, a field that was discovered to him for the first time during the voyage on the Beagle, because he had with him on the voyage the first volume of Charles Lyle's book Principles of Geology: it is an attempt to explain the previous changes before the country with reference to the causes operating now; The second volume was sent to South America and was waiting for him when it arrived named Beagle. Lyle held the belief, revolutionary at the time, that geological transformations and species extinctions occurred gradually and continuously, by virtue of the accumulation of almost imperceptible changes, one after another. These things were in direct contrast to the common thinking of those days, according to which the changes took place rarely and in a catastrophic manner. As Lyle described things, relying on a theory first proposed by a Scottish geologist forty years before him, the world is in a constant state of flux. At the time of his return to London, Darwin already held firmly to Lyell's belief in "uniformitarianism".

Darwin also read zoology and botany books, and thus became acquainted with the work of Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, the Chevalier de Lamarck. Today Sir Kenna of the school named after Lamarck, as it became infamous because of one wrong idea it had: the inheritance of acquired traits. But Lamarckism also included a theory of continuous organic change, which Lamarck presented in his most popular book, Zoological Philosophy (1809). All life arises from the spontaneous formation of very simple life forms, Lamarck said. Using natural liquids that act on coagulated material and "revive" it. The more complex forms of life appear in the way of transmutation - a constant upward progress, in which the nervous fluids carve out for themselves more and more complex pathways from generation to generation. But Lamarck did not see all life today as the descendants of a common ancestor, but believed that organisms at different levels of complexity arose from separate events of spontaneous formation, at different times on the time scale. The higher an organism is in the present, the earlier the appearance of its original ancestor, and therefore it had more time to develop and progress.

New qualities, Lamarck said, are acquired according to the "theory of use and non-use"; Nature permanently exposes its creations to the influence of the environment, and the environment causes changes that affect the electrical or physiological composition of the tissues. These changes do not derive directly from the environment, but rather from the plant or animal's recognition of the need for them. Change is the result of longing for change. And what is equally important. These changes may be inherited, because they have a permanent effect on the reproductive cells.

The most famous example of this theory mentions one of Rudyard Kipling's 'just so' stories, and it can be called "How the Giraffe Got His Long Neck". The story begins with one giraffe in the group, who insists on the need - after eating all the low leaves of the tree, which are easy to access - to reach the higher leaves; Hunger is the driving force. This giraffe has a longing for change. He screws his neck, which increases the flow of fluids to the neck, which lengthens the neck, which affects the fluids even more, which lengthens the neck even more. The lengthened neck, and with it the stronger flow of cellular fluid, is inherited by the offspring of that giraffe. Those long-necked pups come up as bloomers, and in due course turn their long necks into their own pups, and so on through the generations.

Darwin found an analogy for giraffes in domestic ducks, whose legs are thicker than those of wild ducks and their wings are smaller, because they tend to walk rather than fly. From here he began to think about the ability of environmental differences to explain the differences between species. Finally, one autumn day in 1838, Darwin found the long-awaited solution, when he read an old book in a completely different field. It was written forty years before and called "Essay on the Principle of Population", penned by the economist Tomm Malthos. In this book, Darwin found a sentence that captured his imagination and finally brought order and logic to all the thoughts that ran through his mind and breathed life into his notebooks. Malthus spoke of the "war of existence".

Indeed, existence is war, Darwin agreed. Almost every living creature gives birth to many children, and by no means can all of them stay alive for long, given the limitations on the food supply and the parents' ability to protect their offspring from predators. There must be some guiding principle that determines which of the births will live and which will die. Maybe this principle is the adaptation. Darwin knew that there was variation in nature, although he was unable to explain why. Now, in light of these words of Malthus, it was up to him to take the next logical step: usually, changes for the better will be preserved, and changes for the worse. In the context of the war of existence, they will be destroyed.

Darwin's next step was to propose natural selection as a mechanism that separates the changes for good and bad, between the favored and the unfavored. He arrived at this from an analogy to artificial selection in the improvement of plants and animals. In artificial selection, the breeder's intelligence pushes the changes in a certain, predetermined direction. In natural selection, on the other hand, Darwin saw no room for this kind of superior intelligence. He believed that the changes take place without any thought of purpose, without any supernatural factor overseeing them - and this view, some said, turned biology from a rational science to a mechanistic science.

Six years after the vision of the war of existence was revealed to Darwin, an essay was published that gained enormous popularity and made it clear to him how careful he would have to be in proposing his ideas about descent with modifications. The book, a reminder of creation in the wisdom of nature, was considered complete heresy, and its author was careful to keep his name anonymous: his identity remained a secret until his death twenty-seven years later. Admittedly, it was not an easy secret to keep. The book was extremely popular, and sold 24,000 copies in the first ten years after its publication. Naturally, there was much speculation about the author's identity, which ranged between Prince Albert, the Queen's husband, and the geologist Sir Charles Lyell. Basically, it was a book of advocates for transmutation, but it was presented from a theological point of view, with the assumption that the gradual changes of species that take place gradually reveal the Creator's plan. The author attached great importance to the concept of the "divine author of nature", which pushes flora and fauna forward through small cumulative improvements over time, as "the highest and most typical forms are always achieved recently". According to this theory, all changes apply in a stable sequence, a kind of ladder that steadily rises towards a higher level.

In the year of the appearance of Zechar Labrea, Gregor Mendel was busy establishing his position in Brin, spent his time in the alpine garden with his new friend Metosh Klatzel, participated in the discussions of the agricultural association and prepared to study church history and archeology in the theological college of Brin. It must be assumed that he had not heard softly about the heretical view called transmutation, which caused so much displeasure in England - not only among the clergy, but also among the scientists. One of the most influential biologists of those days, Adam Sedgwick of Cambridge University (who once took Darwin the student on a geological expedition, by the way), launched a scathing eighty-five page letter against that little book. "The world is not

suffering vicissitudes,” Sedgwick wrote. "An important principle for us is that things must remain in their proper places, in order for them to work together for some good... [we must not] poison the threads of the exalted thought and the feelings of modesty of our illustrious matrons and maidens by listening to the temptations of this author."

In 1871, shortly after his death, it was discovered that a male author of Creation was Robert Chambers, the essayist and nature lover whose stings were what pushed Thomas Henry Huxley to participate in the debate with Sam Hamsovan. Because he introduced the idea of transmutation to the British public fifteen years before the publication of the Origin of Species, Chambers was involved in paving the way towards understanding the raw principles of evolution, long before Darwin came along and proposed a possible mechanism for its action.

But without intending to do so, he also aroused in Darwin an excessive fear of publishing his own ideas. Knowing full well what a commotion the memory of creation caused, Darwin delayed publishing his theory of natural selection. This was an even greater heresy than Chambers' heresy, because it did not involve any divine plan or higher purpose. To Darwin, variation was completely random; The success or failure of a particular adaptation was a matter of pure chance.

He carefully prepared the ground for the reception of his ideas in the scientific community, when he put into writing in 1842 - his theory of origin with changes. In 1844-, the year of its publication Menor of Creation. Darwin published an essay, at his own expense, and distributed it to a carefully compiled list of scientists he knew and trusted to read his work with an open mind and sympathetic heart: Charles Lyell: the botanist Joseph Hooker; Vasa Gray, American botanist.

From then on he devoted his time to collecting more and more evidence to support his theory. He corresponded with plants and animals. He sent seeds, plants and dead birds with the river's currents, in imitation of the ways in which organisms reach remote islands. He recruited local students to collect reptile eggs. He cured pigeons and slaughtered them to see how, if at all, their internal organs changed. He also did this with ducklings and chickens donated to him by his neighbors. He collected and sorted sea urchins - 10,000 in all - in order to draw conclusions from them about the relationship between evolution and linear sorting, which according to Darwin was a visual illustration of the patterns of branching from common descent. And he did all these in his country house in Daun, which he never left for more than a day or two in a row. Not only was Darwin confined to his residence due to the needs of the household, he eventually had seven children - not to mention several pets and about a hundred pigeons. But he also suffered, upon reaching middle age, from a strange degenerative hangover that no one could explain. Diagnoses later included Chagas' disease, a tropical disease that may have been contracted in South America; psychological distress; multiple allergies; Or accidental poisoning from one of the folk remedies he used to take liberally.

But the time available to Darwin to write his masterpiece was not unlimited, as he thought. A competitor who had developed an almost identical theory was ready and willing, in 1858, to present it to me in the world. Alfred Russell Wallace was a professional collector; He made a living by selling exhibits he collected in his travels around the world. Wallace, like Darwin, first emphasized the diversity of species on a trip to South America. That trip, between 1848 and 1852, was a revelation to Wallace, just as the Beagle trip opened Darwin's eyes. But Wallace had a disaster on his way.

During the voyage back to England his ship caught fire, and all his notes and findings were lost. He recovered his notebooks - and collected the insurance premiums due to him - and immediately set out on the trip, this time to the islands of the Malay Archipelago, now called Indonesia. On the island of Jilloler (also called Kalamahoe), while consumed by the twilight of a tropical fever, Wallace came up with the idea called natural selection by Darwin, and even expanded it further than Darwin.

Wallace accepted the transmutation as a given. In a short essay entitled "On the Tendency of Varieties to Divert Infinitely from the Original Type" he outlined the mechanisms that he believed might activate the transmutation. "The life of wild animals is a war for existence," he wrote. "Those of them that are best adapted to obtain a regular supply of food, and to defend themselves against the attacks of their enemies and the vicissitudes of the seasons, will necessarily risk superiority in the population and strengthen it." In June 1858, she sent a pre-publication copy to the man who knew how to make sure that things would be accepted on his own: Charles Darwin.

Wallace had heard of Darwin three years before, although the two had never met. In 1855, Wallace published an article stating that "every species comes to exist simultaneously, in time and space, with a species that existed even before that, very similar to it." Darwin agreed, and the two began a vigorous correspondence: Darwin was an avid letter writer. But during all this time, the veteran researcher did not reveal to his younger friend that he was working on the development of a theory based on an assumption very similar to Wallace's, and now he had a worked out theory in front of him, a bee on his wheels, that looked almost exactly like his theory. Darwin panicked. For twenty years he used to get up from his sick bed for several hours every day to process the details of the origin with changes, and now the results of his careful slowness were thrown in his face. Another man preceded him - and another just a collector of exhibits.

Darwin's friends decided to establish a possession on his behalf, before Wallace claimed his. "At first I was willing to comply with them," said Darwin in his autobiography, "because I thought Mr. Wallace would find the act unjustifiable." But he agreed anyway, and since there was enough evidence in sight that Darwin had arrived at his theory as early as 1842 - and primarily in the essay he distributed to a small and equal number of biologists - he did not expect any special problems in convincing the scientific community by reaching conclusions similar to Wallace's on his own, as a parallel way . (Despite this, from time to time Plaster's writings accused Darwin of plagiarism, and they still appear today.) On July 1, 1858, Darwin's friends, Lyle and Hooker, read three papers at the Linnaean Society meeting in London: Wallace's paper; Excerpts from Darwin's treatise from 1844; and a letter presenting his theory, sent to Asa Gray on September 5, 1857 - before he read Wallace's essay.

It was the strange shock of the reception that awaited another, equally revolutionary article - the one that Gregor Mendel would read seven years later in Brin: no one gave their opinion on the contributions of Darwin and Wallace. Maybe because the two Like them as Mandel after them, they deviated so far from the conventional thinking of those days. In any case, none of those present at the conference of the Linnaean Society asked any questions, and the entire event was not etched in anyone's memory.

The articles appeared side by side in the association's newsletter. But the double publication, like Mandel's publication, made no waves, not even ripples. Darwin remembered only one answer about the articles, from an Irishman who wrote to him that "everything new in them is false, while the real is the ancient." Now Darwin will change his waist. He has already gathered information from Shabihi

plants and animals, which created new forms of the species they cultivated. But what exactly were these new forms? Deaf varieties? New variations? Completely new species? And what is the mechanism by virtue of which such "crossovers" work?

What he needed most of all was a theory of heredity; His conception of natural selection was only half the work without it. As he saw things, the forces of the environment help to perpetuate the changes that provide what he called a "selective advantage" - a benefit to the animal or plant, which allows them to produce more viable offspring than those produced by competing organisms that do not enjoy this advantage. But how exactly does this kind of trait pass to the next generation? And why does it continue to exist?

Here Mandel could have helped - if he had been one of the two. He or Darwin, is able to see clearly how the random alternation of the units of heredity is able to explain the variations necessary for the operation of natural selection. But Darwin didn't know anything about Mendel, and that was his fault. He himself was not skilled in the use of numbers, and all the other ideas about heredity that existed at the time confused him to the point of helplessness. In truth, his poor math skills put a severe test to anyone who tried to explain to him what heredity was, and in Judaism, his son George and our uncle Francis Gulton. When installed Golton, one of Darwin's closest friends. The "law of inheritance from the ancestors", the narrators turned Darwin's mind (brilliant these days) into porridge. This law introduced a number of fractions as a representation of that part of the inherited traits that a descendant receives from each of his two parents, and from each of his four grandparents, and from the eight parents of his grandparents, and so on. According to this law. Each parent (marked P) contributes a quarter of his own genetic makeup to the offspring. Each of the four grandfathers (PP) contributes an eighth; Grandparents (PPP) – one in sixteen; Great-grandparents (PPPP) - one in thirty-two. In this way, a trait found in the genealogy of any given individual is never lost; She just thins.

Darwin did not develop Golton's theory, or anyone else's, but instead invented his own theory - which did not involve any numerical calculation of any kind. He called it "Fanganza". He said that there are units operating in it which he called "rewards". The rewards, which are produced by the cells of the body, move to the gametes through the blood circulation (or in plant cells, through the internal transport system called the siphon tubes). There the rewards await in a state of dormancy until the moment of fertilization. Then they are passed on to the next generation. Since the rewards originate in the cells of the body, Darwin saw them as a mechanism for inheriting acquired traits. Something in the environment causes the organism's rewards to change, and then they pass to the gametes and pass the changes that occurred on them to the descendants of the animal or plant.

To Darwin, the rewards were also the mechanism of assimilation. Because this was his favorite theory of heredity. But if traits merge, argued his opponents, isn't a new species going to merge quickly with its predecessors. Until he is completely assimilated? According to one of Darwin's harshest critics, the physicist Fleming Jenkin, if a rare mutation appears (he called it a "miracle"), it is destined to disappear as quickly as it came, because the possessor of the mirage is one and only by nature, and therefore must mate with a normal individual. And their own descendants will be "on the whole halfway between the average individual and the mirage". The result, Jenkin said, is rapid disappearance. Or "flooding", of the mutation that appeared randomly, removed from the general pool of differences - like a single drop of red paint in a bucket of white paint: after a few decent touches, no trace of it will remain.

But flooding would not be a problem, Darwin replied, if living conditions continued to change steadily. He has always seen environmental changes as the main source of variation; The changes with the highest adaptive capacity will persist. If a bear that lives in a cold climate accumulates more and more fat, so its chances of surviving the winter are better than those of leaner bears, then its cubs will be born fatter than average to begin with. This idea of the inheritance of acquired traits was one of Darwin's strongest tenets, an incomparably stubborn blind spot in his search for mechanisms to explain the workings of natural selection.

He included this idea with the help of another concept, the increasing hereditary strength of traits in the course of time: this idea was also discarded a long time ago. He called it "Yarle's Law" after his friend William Yarle, a newspaper wholesaler who filled his spare time with "country pursuits" - hunting, gathering and improving homesteads. According to Jarl's law, the oldest traits are the strongest, and have a better chance of being inherited than traits that have recently entered the species. This emphasizes the conservative tendency of nature: whenever a fusion may occur between an old strain and a new strain, it tends towards the older and stronger trait.

Debates with the likes of Fleming Jenkin preoccupied Darwin's supporters for decades. The confrontation between Huxley and the twisted Sam has been repeated time and time again, in stuffy lecture halls, in human courts, and even these days. In the combined offices of educational boards meeting to decide whether evolution deserves to be included in science curricula. When swords were first drawn, in the XNUMXs, one of the most dramatic defenders of Darwin's theories was Francis Goulton.

In the eyes of Golton - a brilliant mathematician, biologist and statistician - everything was quantifiable: the power of prayer, the relative beauty of a woman, the circumference of the waists of members of the British aristocracy over the generations. Goulton was one of the last of the gentleman scientists, those with a guaranteed income who delved into their breeding ideas for pleasure.

that in the matter He took a dilettante approach to his studies as well: while he was a student at a medical school in London, and he was then fifteen years old, he decided to make his way through the pharmacology textbook and try every drug he found there. He started the task in alphabetical order, but only got as far as the letter C, when he was defeated by the kodan oil used to cleanse the intestines. He did not find anything else interesting in the curriculum, so he abandoned medicine shortly after.

Golton threw his hand in everything. He is the one who discovered that the fingerprint is unique to each person. He was the first to name and describe the anticyclone. And in the sixties he spent a large amount of his time trying to help Darwin understand the problems of heredity that had plagued him throughout his life.

Goulton was not a foolish follower of our more famous uncle; In fact, one of the first experiments he set up was designed to show why Rarwin's pangasence theory was wrong. He started with a group of rabbits with fur of different colors, and did inter-colored blood transfusions: a white rabbit received blood from a brown rabbit; A brown rabbit received blood from a white rabbit.

According to Darwin's theory, the rewards were supposed to pass along with the blood, so white rabbits should have become brown, and vice versa. But at the site of Golton's confinement, it was found that the blood transfusions do not affect the color of the offspring's fur in the same way. Whites still gave birth to whites, and browns - browns.

Later in his career, Golton went on journeys to unknown regions in South-West Africa, defined the statistical terms regression and correlation, and coined the word "eugenics" - the social application of genetics to human reproduction, which would later serve as a justification for some of the worst atrocities committed in the name of the final solution. The ethnic cleansing and genocide, in the years of his time. In light of the fact that Golton's name reappears in some of the most heated debates of science in the twentieth century, there is some surprise in the discovery that he was born in 1822 - the year Gregor Mendel was born. It is much more natural to see them as members of different generations.

Golton was blessed with extreme longevity - he was eighty-nine years old when he died in 1911 - and had the privilege of witnessing the first days of the new science of genetics, its most stormy days, and some would say the most fascinating. The two main sides in the struggle that was waged with impressive ferocity in those first years of the twentieth century, especially in England, claimed to be the standard bearers of Darwin on the one hand and Mendel on the other. But each side also put at its head a leader who gave it its inspiration; And both parties alike singled out that role for Golton.

Indeed, Golton inspired those who became Darwinians, as well as those who called themselves Mandalaists. But while Mendel was engaged in his work, in the early sixties, Gulton knew nothing about him. At the time, Darwin was causing huge waves of hysteria throughout Britain, Europe and America, and Goulton devoted his time to explaining Darwin to Darwin's colleagues and explaining Darwin's colleagues to Darwin. And during all this time Mendel - Golton's exact age - created a storm of his own, of a completely different kind. Mendel's turmoil raged mostly inside his own head as he walked among the gloriously growing vegetables in his quiet Moravian garden. And this storm did not erupt with all its loudness until the end of forty years.

Yaden Darwin and the politics surrounding the theory of evolution

To purchase the book 'The Hermit in the Garden' from the Mythos website