The first step in unraveling the puzzle of the origin of human consciousness is to determine what distinguishes our mental processes from those of other creatures.

By Mark Hauser

Not long ago, three extraterrestrials descended to earth to assess the state of intelligent life in the world. One specialized in engineering, one in chemistry, and one in computing. The engineer turned to his companions and said (the translation is in front of you): "All the creatures here are solid, some are articulated, and have the ability to move on land, in water and in the air. They are all terribly slow. They are not impressive.” After him the chemist said: "They are all quite similar, built from different sequences of four chemical components." Then he contributed his expert opinion on calculability: "Calculation capacity is limited. But one of them, the hairless biped, is unlike the others. He exchanges information in a primitive and inefficient way, but in a very different way from the others. He produces various and strange objects for the most part, some of which are edible, some of which produce symbols, and some of which destroy the members of his tribe."

"But how is that possible?" asked the engineer. "If they are similar in form and chemistry, how is it that their calculation ability is different?" "I'm not sure," the calculating extraterrestrial confessed. "But they seem to have a mechanism for creating new expressions that is infinitely more powerful than all other living things. I suggest that we classify the hairless biped in a separate group from the other animals, as having a different origin and a member of a different galaxy." The other two aliens nodded, and all three rushed home to submit the report.

Our outside reviewers cannot be blamed for classifying man in a separate group from the bees, birds, beavers, baboons and chimpanzees. Isn't it just our species that produces souffle, computers, guns, make-up, plays, operas, statues, equations, laws and religions. The bees and baboons, not only had they never made a soufflé, they had never even thought of the possibility. They simply do not have the brains endowed with the technological know-how and gastronomic creativity necessary for this.

Charles Darwin, in his book "The Descent of Man" published in 1871, claimed that the difference between human consciousness and the minds of other creatures is a difference of "degree, not kind." This opinion, supported by genetic studies that found in recent years that we share about 98% of our genes with chimpanzees, has been accepted by scientists for many years. But if our shared genetic heritage does indicate the evolutionary origin of human consciousness, then why isn't a chimpanzee writing this article, or singing the "Rolling Stones" songs, or making a souffle? Indeed, the accumulated evidence shows that, unlike Darwin's theory about the continuity of consciousness from man to other species, there is a deep gap between our intellect and that of animals. This is not to say that our mental skills emerged in their entirety from nowhere. Although some of the building blocks of human consciousness have also been found in other species, they are but the tip of the mighty structure that constitutes human consciousness. The evolutionary origins of our mental abilities are still shrouded in obscurity. However, insights and innovative experimental technologies are beginning to clarify the picture.

Smart like us

If we scientists ever want to discover how human consciousness came to be, we must first clarify for ourselves what distinguishes it from that of other creatures. Although humans share most of their genes with chimpanzees, it seems that small genetic changes that have occurred in the human lineage since it split from the chimpanzee lineage have caused huge differences in computational ability. Reorganization, deletion, and copying of universal genetic elements created a brain with four special features. These distinct characteristics, which I have recently defined based on research conducted in my lab and elsewhere, together create what I call humaniqueness, or human uniqueness.

The first of these features is the generative calculation. The ability to create an infinite variety of "expressions" for anything: sets of words, sequences of characters, combinations of operations, or strings of mathematical symbols. A generator calculation includes two types of operations: a circular (recursive) operation and a French (combinatorial) operation. The circular operation reuses rules to create new expressions. Consider the fact that it is possible to insert a short phrase inside another phrase, over and over again, and thus create longer and richer descriptions of our thoughts - for example, Gertrude Stein's simple but poetic sentence: "A rose is a rose is a rose." The connecting action makes use of discrete elements and combines them to create new ideas, which can be expressed as new words ("school"), as musical structures, or in a variety of other ways.

The second feature that distinguishes the human mind is our ability to match ideas casually. We tend to combine thoughts from different fields of knowledge, with our insights on art, sex, space, causality and friendship intertwining. This fusion sometimes brings up new laws, technologies and social relations, as for example when we decide that it is forbidden [the domain of morality] to intentionally push a person [the domain of motor activity] [the domain of folk psychology] under the wheels of a speeding train [the domain of objects] in order to save their life [the domain of morality] of five [the field of numbers] other human beings.

Third on my list of essential features is the use of mental symbols. We can spontaneously transform any sensory experience - real or imaginary - into a symbol, which we can keep to ourselves, or share with others through language, art, music or computer code.

Fourth, only humans think abstract thinking. Unlike the thoughts of animals, which are anchored mainly in sensory and perceptual experiences, our own thoughts do not, in many cases, have a clear connection to such events. Only we alone think of dragons and extraterrestrials, nouns and verbs, infinity and God.

Although anthropologists differ in their opinions on the exact time when modern human consciousness took shape, archaeological findings clearly indicate that within a short evolutionary period a considerable change took place, which began about 800,000 years ago, in the Paleolithic period, and which reached its peak about 45,000 to 50,000 years ago. In this period, no more than an evolutionary blink of an eye, multi-part tools are seen for the first time; pierced animal bones for use as musical instruments; Burial of a person next to accessories indicating beliefs related to aesthetics and the afterlife; Cave paintings are rich in symbols that describe in detail events from the past and the foreseeable future; and control of fire, a technology that combines folk elements of physics and psychology, which gave our ancestors the ability to successfully cope with new environments by producing heat and cooking food to make it edible.

These relics from our past are glorious reminders of how our ancestors faced new environmental problems and struggled to express themselves in new and creative ways to express their cultural identities. However, the archaeological evidence will forever remain silent as to the origins and environmental pressures that led to the four components that make up our human uniqueness. The magnificent cave paintings in Lascaux in France, for example, imply that our ancestors understood the dual nature of images - that they are both objects and represent objects and events at the same time. But they do not reveal whether those painters and their admirers expressed their aesthetic preferences about these works of art through symbols organized into grammatical groups (nouns, verbs, adjectives), or whether they thought that these ideas could be equally expressed in sounds or signs - according to the correctness of their sensory systems. Similarly, the ancient musical instruments found, such as 35,000-year-old bone and ivory flutes, do not tell a story about their use, if they were repeatedly played a handful of single notes, in the style of Philip Glass, or if the composer conceived in his imagination, like Wagner, themes within circularly integrated themes .

What we can say with complete confidence is that all human beings, from the hunter-gatherers of the African savannah to the traders on Wall Street, are born with the four elements of human uniqueness. But combining these ingredients into a recipe for creating a culture varies greatly from group to group. Among the different human cultures there are differences in language, musical compositions, morals and objects. From the perspective of one culture, the customs of another culture are often strange, sometimes repulsive, in many cases incomprehensible, and occasionally immoral. No other animal exhibits such diversity in its lifestyles. In this view, chimpanzees are cultural failures.

But chimpanzees and other animals are still interesting and relevant to understanding the origin of human consciousness. In fact, only if they decipher which abilities we share with other animals and which are ours alone can scientists hope to add the pieces of information to the story of the emergence of human uniqueness.

A Beautiful Mind

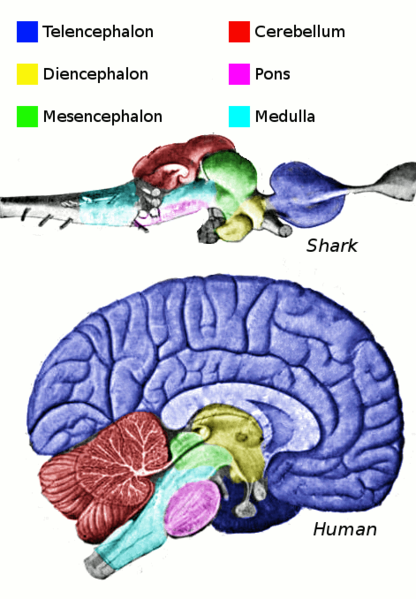

When my youngest daughter, Sophia, was three years old, I asked her where our thoughts come from. She pointed to her head and said: "My brain." I added and asked if animals have brains, dogs and monkeys first, then birds and fish. she said yes. When I asked her about the ant walking at our feet, she said: "No, it's too small." We, the adults, know that size cannot be used as a measure of the existence of a brain, even though it affects various aspects of the structure of the brain and consequently some of the aspects of thinking. Studies have shown that most of the different types of brain cells, based on their chemical messengers, appear in all vertebrate species, including humans. Moreover, the general organization of the various structures in the outer layers of the brain is very similar in monkeys, apes and humans. In other words, humans have some brain characteristics in common with other species. The differences are evident in the relative size of certain areas of the cerebral cortex and in the connections between these areas, differences from which arise thoughts unmatched throughout the animal kingdom.

Even among the animals one can find sophisticated behaviors, which seem to foreshadow some of our abilities. Take, for example, the ability to create or modify objects for certain needs. The male woodpecker builds magnificent architectural structures and decorates them with feathers, leaves, buttons and the color of crushed berries to attract the female. New Caledonian crows carve sticks from branches to catch insects. Chimpanzees have been observed using pointed wooden sticks to impale tiny primates hiding in tree crevices.

Moreover, studies of some animals have revealed that they have an intuitive understanding of physical laws, which allows them to make generalizations beyond their direct experience to create new solutions when exposed to unfamiliar challenges in the laboratory. In one of the experiments, orangutans and chimpanzees were given a plastic cylinder with a peanut on the bottom. They obtained the coveted delicacy by sipping water and spitting it into the cylinder, until the peanut floated on the surface of the water and reached their reach.

Animals also show social behaviors similar to those of humans. Veteran ants impart knowledge to new students by directing them to food sites. Meerkats give lessons to their young in the art of dismembering deadly but palatable scorpions. Many studies have shown that many different animals, such as domestic dogs, capuchin monkeys and chimpanzees, protest unfair distribution of food and demonstrate a behavior that economists call "injustice aversion". More than that, there are animals that take care of puppies or look for mates or coalition partners. They are absolutely ready to respond to new social situations, such as when an individual from an inferior status who is endowed with a unique skill therefore receives benefits from individuals with a dominant status.

Such observations evoke a vibration of astonishment at the beauty of nature's R&D solutions. But in the passing of the vibration, we must stand on the gap between humans and the other species, a huge and wide gap, as our extraterrestrials have reported. To illustrate the dimensions of this gap and the difficulty in deciphering the puzzle of its formation, I will describe human uniqueness in more detail.

great abyss

One of our most basic tools, the No. 2 pencil, used by everyone ever tested, demonstrates the extraordinary freedom of human consciousness compared to the limitations of animal cognition. You hold the painted wood, write in graphite and erase with the pink eraser fixed in the metal hoop. Four different materials, each with a special function, all combined in a single tool. And even though this tool was created for writing, it can also be used to gather hair into a bun, mark a page in a book or stab an annoying insect. Animal tools, on the other hand - like the sticks used by chimpanzees to fish termites from their hangings - are made of a single material, serve a single purpose and are never used for other purposes. Not a single one of them has the combined properties of the pencil. Another simple tool, the folding telescopic mug found in many camping kits, is an example of circularity in action. To produce this device, the manufacturer only needs to program a simple rule - add a larger segment to the previous segment - and repeat the operation until the desired size is achieved. Humans use circular actions like this in every aspect of mental life, from language, music and mathematics to producing an unlimited variety of movements with our legs, hands and mouth. The faint circular flashes in animals, on the other hand, are observed only in the action of their motor systems.

All creatures are endowed with circular motor mechanisms as part of their basic operating equipment. To walk, they put one foot in front of another, over and over. To eat, they may grab a food item and bring it to their mouth repeatedly until their stomach signals to stop. In animals, this circuit system is locked in the motor areas of the brain, without access to other brain areas. Its existence implies that a critical step in the formation of our unique thinking was not the evolution of circularity as an innovative form of calculation but its release from the motor prison into other areas of thinking. The way we got out of this limited function connects to one of our other features - mixed interfaces - which I will talk about right away.

The mental chasm widens when we compare human languages to communication in other species. Like other animals, humans have a non-verbal communication system that conveys our feelings and the factors that motivate us - the giggles and cries of small babies are part of this system. But only humans have a linguistic communication system based on the use of mental symbols and their processing. We classify each symbol into a specific, abstract category such as a noun, verb, or adjective. Although there are animals that make sounds that probably represent more than emotions, and convey information about objects and events such as food, sexual activity, and the presence of a predator, the range of these sounds pales in comparison to ours, and none of them belong to the abstract categories from which our linguistic expression is built.

This claim needs clarification, as it raises a lot of skepticism. One might think, for example, that the vocabularies of animals seem small because the researchers who study their communication do not understand what they are talking about. Although scientists have a lot to learn about the sounds of animals, and communication more generally, I believe that this is not enough to explain the large gap. The exchange of sounds between animals usually amounts to a growl, or a growl, or a single scream from each side. A growl of 500 milliseconds may contain a lot of information - say, something like "scratch my backside now, and I'll scratch your back later." But why then did we humans develop such a complex and wordy system if we could solve everything with a grunt or two?

Moreover, even if we agree that the bee's dance symbolically represents the delicious pollen two miles north of the hive, and that the various warning calls of the white-nosed gardener symbolize different predators, these uses of symbols differ from ours in five different ways: what evokes them is always objects or actual events, never imaginary; They are limited to the present; They are not part of a more abstract system of classification, like the one that sorts our words into nouns, verbs, and adjectives; They are almost never combined with other symbols, and if so, the combinations are limited to a string of two, with no rules; And they are fixed to certain contexts.

Human language is special and completely different from the communication systems of other animals also in its adaptation to two modes of action, auditory and visual, in equal measure. A songbird that loses its voice or a bee that loses its ability to dance will not be able to continue communicating. But for a deaf person, sign language is an effective means of communication and has a structural complexity just like using voice.

Our linguistic knowledge, with the calculations it requires, also works with other fields of knowledge in fascinating ways that beautifully reflect our unique human ability to make wild connections between systems of understanding. Think about the ability to quantify objects and events, an ability we share with other animals. A wide variety of species have at least two non-linguistic abilities to count. One is exact and limited to numbers smaller than four. The other is not limited in range, but is approximated and limited to certain number ratios: an animal that can distinguish between one and two, for example, can also distinguish between two and four, between 16 and 32, and so on. The first system is anchored in the area of the brain that deals with tracking details, while the second is anchored in the areas of the brain where computers grow.

In 2008, my colleagues and I described a third counting method in rhesus monkeys, one that may help us understand the origins of the human ability to distinguish between singular and plural. This system works when a group of objects are presented simultaneously - as opposed to individual objects presented one after the other - and allows rhesus monkeys to distinguish between one food item and many items, but not between many and many. In our experiment, we showed a rhesus monkey one apple and placed it in a box. We then showed the same monkey five apples and placed all five at once in a second box. When given a choice, the monkey always preferred the second box, which contained five apples. Then we put two apples in one box and five in another. In this case the monkey did not show a fixed preference. We humans do the same thing, basically, when we say "one apple" and "three, five or a hundred apples."

But something unusual happens when the human linguistic system connects to this primitive system of perception. To see this, try this exercise: to the numbers 0, 0.2 and -5, add the most suitable word: "apple" or "apples". Most of us, including small children, chose the word "apples". In fact, we were chosen in "Apples" also for "1.0". If you are surprised, indeed, you should be. This is not a rule we learned in school - in fact, to be precise, it is not grammatically correct. But this is part of the universal grammar that only we are born with. The rule is simple but abstract: anything that is not "1" is plural.

The example of the apple illustrates how different systems - syntax and group perception - work together to create new ways of thinking or conceptualizing the world. But the creative process in humans does not stop here. We apply our language and number systems in cases of morality (it is better to save five people than to save one), economics (if I give 10 shekels and offer you XNUMX shekel, you will find it unfair and reject the shekel), and forbidden barter transactions (selling children, even For a lot of money, it is not kosher).

foreign thoughts

From the didactic meerkats to the unjustly averse monkeys, the observations remain: each of these animals has developed superior thinking adapted to unique problems and is therefore limited in applying skills to solving new problems. Not so with us, the bald bipeds. After our ancestors developed modern consciousness, it allowed them to go out and explore new and uninhabited areas of the earth, create language to describe new events, and envision an afterlife.

The roots of our mental abilities are largely unknown, but after scientists identified the unique components of human consciousness, they now know what to look for. In this search, I hope neurobiology will enlighten us. Although scientists still do not understand how genes build brains and how electrical activity in the brain builds thoughts and emotions, we are witnessing a revolution in neuroscience that will fill in the gaps and help us understand why the human brain is so fundamentally different from the brains of other creatures.

For example, studies on chimeric animals - in which brain circuits from one species have been transplanted into another species - help to discover how the brain is wired. And in experiments where the genomes of animals are changed, genes with roles in language and other social processes are discovered. These achievements do not reveal what our nerve cells do to give us our unique mental ability, but they outline a road map for further research into these qualities.

Still, for now, we have no choice but to admit that our consciousness is very different from even our closest primate relatives, and that we don't know much about how that difference came about. Can chimpanzees design an experiment to study humans? Can they imagine what it would be like for us to solve one of their problems? no and no. Although chimpanzees can see what we do, they cannot imagine what we think or feel because they lack the necessary mental machinery to do so. Although chimpanzees and other animals sometimes seem to develop plans and examine past experiences and future possibilities together, there is no evidence that they think in terms of "what if" - imagining worlds that were and contrasting them with ones that could have been. We humans do this all the time and have done so since our special genome gave birth to our special consciousness. Our moral systems are based on this mental capacity.

Has our unique consciousness reached its peak? In every form of human expression - including the various languages of the world, the musical works, the moral codes and the technological forms - I suspect that we will never be able to exhaust the space of all possibilities. There are serious limitations to our ability to imagine alternatives. If there are substantial limitations to what our intellect is capable of absorbing, then the concept of "thinking outside the box" is fundamentally wrong. We are always inside the box, limited in our ability to foresee alternatives. Thus, just as chimpanzees cannot imagine what it is like to be human, so humans cannot imagine what it is like to be an intelligent extraterrestrial. Any attempt to imagine will run into the walls of the box we call human consciousness. The only way out is through evolution, a revolutionary structural change in our genome and its potential to shape new connections between nerve cells and create new neural structures. Such a change will give birth to a new consciousness, which will look at its ancestors as we look at our own: with respect, with curiosity, and with the feeling that we are here alone, masterful creatures in a world of simpletons.

About the author

Mark Hauser is a professor of psychology, human evolutionary biology, and organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard University. He studies the evolutionary and developmental foundations of the human brain, with the aim of determining which mental abilities humans share with other animals and which are unique to us.

The question of size

Humans are smarter than creatures whose brains are bigger than ours in absolute terms, such as the killer whale, and also creatures whose minds are bigger than ours in relative terms (that is, in relation to their body size), such as the humpback whale. Size alone therefore does not explain the uniqueness of a person's mind.

The brain of a killer whale

5,620 g

human brain

1,350 g

Etruscan brain

0.1 g

And more on the subject

The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve? Marc D. Hauser, Noam Chomsky and W. Tecumseh Fitch in Science, Vol. 298, pages 1569–1579; November 22, 2002.

Moral Minds: How Nature Designed Our Universal Sense of Right and Wrong. Marc D. Hauser. Harper Collins, 2006.

Baboon Metaphysics: The Evolution of a Social Mind. Dorothy L. Cheney and Robert M. Seyfarth. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

33 תגובות

This is a very interesting article

In total, so far we have four participants in this discussion:

Yair Shimron, point, author of the article and selfish.

Of the four of us - three do not accept Yair Shimron's definition of abstract thinking.

A statistical refutation of the claim that Yair Shimron's definition of abstract thinking is the accepted definition is accumulating here.

Yair Shimron:

And in relation to your words to the point - it seems to me that you did not understand his words.

He did not claim that thinking does not take place in the brain but that not everything that takes place in the brain is thinking and not all thinking is abstract thinking.

Yair Shimron:

I really don't understand your insistence.

I talked about the fact that it is possible to disprove the claim that a certain definition is the accepted definition by statistics, but beyond the fact that these statistics are difficult to perform reliably in any case, it is not at all possible in a conversation between two people.

When you wrote "You are welcome to refute my definition" it was part of a conversation between two and in such a conversation there is no way to refute even statistically because each of the positions has exactly one supporter.

This sentence of yours was the basis of the debate, so please - don't explain to me now what I explained to you earlier - that when there are more people and it is possible to do statistics, there is a significance in refuting the claim that a certain definition is generally accepted (which, of course - it is also not a refutation of the definition because the only thing that can be refuted are claims and a definition in itself is not a claim).

I also demonstrated to you that in the conversation between us and the author of the article there is already a statistic of two against one regarding the definition of the term "abstract thought"

Michael,

There is a thing called an idiolect, a man's talk with himself. In this he is not obliged except for his own taste. When two people talk they need agreements. When many people participate in the conversation, the agreements should be broad.

A dictionary can only define words with words that people understand, that is, agree on their meanings. Therefore, the linguistic tolerance for differences between word definitions of dictionaries is very limited.

Even when it comes to terms there is only limited tolerance. If I define a table as a writing instrument, a person can find a reason for the definition, and still reject it as absurd. If a table is defined as a pet, any speaker of the language we use (Hebrew, Israeli, knowledgeable) will reject it as absurd, even though the definer will say that the table has four legs.

The possibility to define is not unlimited, therefore it is possible to refute a definition.

point,

Once upon a time it was believed that they thought in the heart, kidneys, and liver.

"Every thinker knows what it is to think" - a sentence (not a definition) as absurd as it is. So far, neither scientists, nor your people, nor those whose names we have forgotten, do not really know how to explain the thinking.

In any case, except for you, almost every person will say that thinking is done in the brain, in brain processes.

"If a person's brain processes are considered thinking" where did you see that the brain processes are considered thinking? Thinking is thinking (every thinker knows what thinking is), and a mental process is a mental process.

Yair Shimron:

It doesn't matter at all how many times you repeat the claim that a definition can be refuted - it won't help. It is irrefutable and all you can do is accept it or not.

This is the definition of the term definition. This is a word derived from the word "fence".

By definition you determine what it symbolizes in your eyes and no one has the authority to determine better than you what something symbolizes in your eyes.

All others can do is say "I wouldn't define it that way" or "most people define it differently so if you use that definition they won't understand you" and things like that.

A refutation is really irrelevant because a refutation applies to objective claims, whereas here it is a subjective claim. No one but me can claim to know better than I do about the meaning I attribute to this or that phrase.

Objective claims about definitions are statistical claims like "the majority of the public would accept such and such a definition".

This is an objective claim and therefore it can be confirmed (actually even verified) or refuted, but this can only be done by questioning a sufficiently large part of the people who make up that public. Confirmation and refutation come in this context only from the experiment and not from a deductive logical process that someone can carry out on their own.

Therefore - even on objective claims in relation to the definitions, you cannot appeal from logical considerations.

The restriction dictated by the other words is really zero. What is the connection between "got out", "martaz" and "sack" and "the adze came out of the sack"?

There is no connection. Context is an agreement that is based on a particular culture.

You write "But we must ask what about all the tiny and small and medium gap perfections, long before dragons, that make both men and animals."

And I answer - if we have to then we have to but do we have to call these perfections abstract thinking? no and no!

I certainly think that the ability to create symbols and do so in a recursive process is uniquely human.

I also think that the ability to understand the concept of "symbol" is unique to man.

In my opinion - and I assume also in the eyes of the writer - abstract thought is a quasi-mathematical thought in which the processing is done on symbols and not on concrete entities.

And when I say "symbols" I mean the symbols we consciously created and not the physical representation of a "lion" in the monkey's mind.

It turns out, therefore, that I define "abstract thinking" differently than you define this term.

It turns out that the author of the article defines abstract thinking in a similar way to how I define it.

Who is right? This is a meaningless question. We are all right because we make claims that do not contradict each other.

I claim that I define it this way and you claim that you define it differently.

Does it make sense for me to come and argue to you "Wrong! You define it exactly like me!"?

There is no logic in this.

And what about the meaning of the term in the general public?

Here a statistical test is needed.

So right now it's two against one, but it's obviously far from being a statistic based on which it can be argued how most people define abstract thinking (which is also certain that most people have never bothered to construct a definition for themselves for this term).

point,

The brain has been studied using the brains of mice and rats and monkeys and insects and fish. All brains work in the same basic ways. If a person's brain processes are considered thinking, the same basic processes in a chimpanzee are thinking, and in a rat and in any brain.

Yes, necessarily thinking.

We cannot interpret and redefine every word and term in every discussion.

There are quantitative and qualitative differences in the thinking of the different minds, but the principle processes are similar to the point of equality.

Abstract thinking does not begin with mathematics, but with the completion of tiny gaps between the sensory input and the actions derived from these completion processes.

Michael,

Your definitions refer to the access of word dictionaries. These dictionaries, also of the same language, are written for a reader who is considered ignorant. If it is explained to him that thinking is corn, he cannot dispute the definition, unless he obtains more information.

In our discussion the words and even the terms are already known to a large extent, if also vaguely. We are not allowed to define thinking here as we please. Bending the knee can be interpreted as a result of thinking, not as thinking.

Thinking, in the discussion here, is only brain processes.

We definitely use language thanks to agreements. Therefore you are very limited in every setting. Therefore, definitions of terms that follow actually create new, more precise, rebuttable agreements.

If the author of the article claims - "Only humans think abstract thinking. Unlike the thoughts of animals, which are anchored mainly in sensory and perceptual experiences, our own thoughts do not, in many cases, have a clear connection to such events. Only we alone think of dragons and extraterrestrials, of nouns and verbs, of infinity and God " - we understand that he begins the definition of abstract thinking at levels that can be described as "high", but we must ask what about all the tiny and small and medium gap perfections, long before dragons, which both humans and animals do.

How do we explain the fact that a dog changes its direction in a chase that does not follow the movement of the chased, that a chimpanzee is capable of several intermediate actions to achieve a goal, that a crow is able to initiate a series of indirect actions from food containers, when we know that brain processes are not fundamentally different between animals and humans.

The author of the article tells us that all animal actions are related to sensory and perceptual experience. This is XNUMX% true for humans as well. The ability to think about dragons and God and mathematics is built on early perceptual experiences. A baby does not invent any dragon or prove properties of right triangles.

In another passage the author tells us that only people use symbols. A symbol is a thing that stands against another thing. A word stands against something in reality, let's say the word horse against some animal. But also almost anything can symbolize something else, such as a piece of painted cloth that symbolizes a people and a country.

The Pavlovian effect demonstrates how a sound symbolizes food to an animal, just as words can symbolize sex or food to a person, and just as the dog unconsciously prepares for food following the sound, a person prepares by the same means for sex and food following the words.

Eddie:

You are just pasting my opinions and protesting them.

When did I say it's all genetics?

point:

Regarding your response on the 11th - due to your concern, you are of course exempt from reading and referring to my responses. It does not raise or lower anyway.

Michael Rothschild,

To your response on the 12th: Not everything in the scientific community believes that 'everything is genetics'. It's even quite likely that it's not all genetics.

The dispute - apparently it is abandoned between you and part of the scientific community, and within itself.

Shimron you are funny.

"I presented actions of animals that are necessarily the result of thinking" you assume that those actions are necessarily of thinking, and from this you prove that the animals think.

entertaining.

With regard to phrases that have changed their meaning, perhaps it is better to avoid in advance the dogmatic implications of some people and to use the phrases "because from Zion will come the Torah" or "Ahithophel's advice"

Yair Shimron:

Not true.

A definition cannot be disproved.

It is possible to argue that the definition is different, but this is a claim that has no strength of its own against the opposite definition.

I can literally define abstract thought as thinking about naked people and all you can do to deal with this definition is to say "not true, abstract thinking is so and so".

If we were both alone we could continue to argue forever instead of understanding that language (including the definition of terms in it) is only a matter of agreement.

It is possible to accept your definition and choose a different nomenclature for my definition and it is also possible the other way around.

If we are not alone - the logical way to decide would be to compile statistics and determine which definition seems more appropriate to most people.

This is how language works and this is how it happened that all kinds of words like "finish" or phrases like "it's a shame about time" changed their meaning. It also happens that there are different languages in general and the word "enough" has a different definition in Hebrew than in English.

to the point,

I presented the actions of animals that are necessarily the result of thinking. There is no animal action at all without the brain-thought mechanism. If there is a gap between the act and the sensory input that precedes the act, the gap is filled by a hypothesis, which is abstract, and is followed by an action that relies on the abstract completion of the gap. The examples I gave indicate such phenomena in animals. I did not confuse the factors at all, and the computer example is irrelevant.

Michael,

Definition can be disproved. The words and sentences used for the definition must answer the question of what the defined thing is and what its properties are. Sometimes definitions answer this question partially, in a way that changes the description of the defined, by denying its value, by adoring the defined, and more. Such definitions are not rare and are between far-fetched and insufficient.

I also gave demonstrations of abstract thinking in animals. These demonstrations in themselves show that the claim that animals do not have abstract thinking is wrong, as defined by the author of the article.

Avi,

There are no holes in evolution, but the explanations of the mechanisms of evolution are far from satisfactory. There are phenomena in the world of life that are not well explained. Also out of the millions of experiments that have been done, tell me about a successful one.

Yair Shimron, you are confusing thought with action. According to this confusion of yours even a computer has abstract thought. It assumes that you will type on the keyboard and therefore it waits for you to type on the keyboard.

Yair Shimron:

No need for any lubrication.

A definition cannot be refuted because it is a definition.

If you define abstract thought as yellow kernels then corn has abstract thought and man does not.

Claims can only be made about a specific thing.

When you don't know how a person defined "abstract thought" (and you rightfully complain that he didn't share his definition with us) you are not allowed to claim that he is wrong because - as mentioned - you do not know what the definition he is talking about is.

You can snicker all you want, but the scientific mechanism has proven itself. Not only are there no holes in evolution, precisely because of its sensitivity it was called a challenge the most times and in millions of experiments it succeeded time after time.

Michael,

Your iron sense needs some lubrication.

I defined what abstract thinking is and gave some examples to show it in animals. There are countless more examples.

You are welcome to refute my definition and its demonstrations.

The writer, who probably did not investigate the question for the purpose of his article, used the usual arsenal of routine opinions.

Therefore he was wrong, unless my claims are wrong as you are welcome to show.

Yair Shimron:

I do not express an opinion about the abstract thought of animals precisely because of the reason that brought you to an opinion.

As long as there is no definition of what it is about - it is impossible to answer the question.

Among other things - it is impossible - without such a definition - to claim that the author of the article is wrong.

All you can conclude is that the author of the article probably referred to a different definition than yours.

Eddie:

There is disagreement on these points between you and the scientific community.

The question is whether in every discussion there is a place to discuss it.

In my opinion, no way.

Eddie, when you write too many things that can be written in a few lines, I fear serious brain confusion. And I try not to read. Time is short. And what's more, the things I said in my response do not need an answer or a position, these are simple and clear things.

Avi Blizovsky

About a hundred years ago, scientists like you thought that all questions were cracked except for some questions such as black body radiation and the like.

The number of holes that exist in the theory of evolution is large to the eye tenfold and you are sure that it is irreplaceable.

And in your opinion, it is also forbidden to disagree with the opinions of the experts in the field.

Please allow me to chuckle in the face of such thoughtless thinking.

point,

In response 8 I tried to clarify my position also in relation to your comment in response 6.

Avi Blizovsky,

I do not wish to grind ground flour, and once again discuss the issue of 'evolution' yes or no, and if so how much and how, etc.

I meant to talk about something else - in the very specific context of the subject of the article - the development of consciousness. In the first quote I gave in post 4, I wanted to highlight that the author's overt/hidden assumptions are that -

1. Everything is 'genetics', that is, genetics is responsible for all mental skills and mental traits,

2. In the context of the 'development' of consciousness - 'everything is evolution' at the genetic level.

The second quote I brought from the author's words does not confirm the 'assumption' in any way, of course, and therefore it is understood that it is not possible that this is a conclusion. This is an assumption that is a 'hypothesis'.

Assumption 1 - is an assumption that needs a lot more research in order to decide on its validity. There are grounds for saying that mental skills and mental traits do not necessarily (or always) have a direct and complete causal relationship, or even an indirect one - with a defined genetic makeup, or even with a defined physical condition. Although, in some cases there is and is a correlation between skills and traits on the mental level and the genetic makeup/physical condition.

Assumption 2 - is also an assumption that needs a lot more research in order to decide on its validity. It is necessary to find out whether, and especially to what extent - evolution at the genetic level can be responsible/exclusively responsible/mainly responsible for the evolution of consciousness.

Only after a conclusion regarding the validity of the above assumptions, it will be legitimate to think that all that remains is to find out the manner and way of the genetic variation and its creation, as far as the things are related to some kind of development of consciousness.

Of course, in discussion and even in scientific research, the above chronological logical procedure is not maintained. The research makes assumptions for practical needs, even before these assumptions have been adequately 'proved' at the principle level. But it is advisable to always remember, during the research, and especially in an article that has a didactic content and trend, that there is a difference between a 'proven' assumption (that is, with a high probability of the validity of 'truth') in principle and a practical assumption, and between a conclusion, and there is more to establish (including, and especially in the specific matter at hand) - fundamental intelligence. It sometimes happens that one forgets the above differences, or one forgets to point them out. Regarding the current article - I came in my previous response only to point it out.

.

The claim that only humans think abstract thought is wrong.

The writer does not clarify what abstract thought is. Here is a suggested definition: an assumption or conclusion not directly related to sensory input. Do the words assumption and conclusion sound ridiculous in the context of animals? Many cases are known in which animals wander in wide and complex areas to find food. They assume that in certain places they will find food, but did not receive any immediate sensory sign. Anyone who watches cats can see that they pass through many yards where food may be found, break into unfamiliar homes. These activities are the result of abstract thinking.

Anyone who has seen a dog chasing a cat may have seen how, when the cat turned ninety degrees, the dog turned at an obtuse angle to shorten the way, even before the cat reached the point estimated by the angle of the dog's turn. This is an abstract conclusion, since a dog needs a calculation ability that is not found in the sight of his eyes. Those who have watched the crows can see many cases of actions arising from abstract thinking about various cases. In monkeys, and in particular in chimpanzees, many cases have been observed of the ability to perform a series of actions in order to reach an unattainable goal directly.

The difference between a person's ability to abstract compared to animals is in scope, quality, but not in principle.

Eddie,

There are other concepts that indicate the level of probability beyond assumptions and information. And the author writes as you quoted "it seems that".

Eddie, do you think it is serious that every scientist will open up the theory of evolution anew in every article or is it also allowed in this scientific field to rely on the shoulders of giants who have already examined the subject and continue a specific study.

The author writes:

"Although humans share most of their genes with chimpanzees, it seems that small genetic changes that have occurred in the human lineage since it split from the chimpanzee lineage have caused enormous differences in calculation ability."

And I ask: is this an assumption or a conclusion?

The author continues:

"Still, for now, we have no choice but to admit that our consciousness is very different from even that of our closest primate relatives, and that we don't know much about how this difference came about."

So (at least for the time being) - it seems that with the author - this is an assumption...

Interesting links about the brain -

1. London and Kirschenbaum interview, The Computer Brain Project:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0AR1cUlhTk

2. "From synapses to free will", a fascinating course on the subject of the brain:

http://www.youtube.com/view_play_list?p=D8C99F67C81778E8

3. A particularly fascinating lecture by the head of the project (a bit slow loading) is recommended

Enlarge to full screen (using the button under the video window)

http://ditwww.epfl.ch/cgi-perl/EPFLTV/home.pl?page=start_video&lang=2&connected=0&id=365&video_type=10&win_close=0

4. A short interview with Idan Segev:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bz5IUaRr8No

5. The artistic mind:

http://switch5.castup.net/frames/huji/20061112_HUJI_PPT/Main.asp?Lang=HE

6. Fascinating audio file on the subject of the project, right mouse click

and saving on the computer as an MP3 file:

part 1 -

http://sites.google.com/site/highqualitytts/Home/files/BBP_Part_1.mp3

part 2 -

http://sites.google.com/site/highqualitytts/Home/files/BBP_Part_2.mp3

7. Interesting PDF document, right click and "save as":

http://www.odyssey.org.il/pdf/עידן%20שגב-מסע%20מודרני%20אל%20נבכי%20המוח.pdf

8. The project for cracking the secrets of the brain:

http://www.themedical.co.il/Article.aspx?itemID=1868

9. The singularity is near:

http://www.tapuz.co.il/blog/ViewEntry.asp?EntryId=1065939

Interesting article. And indeed the direction is right, consciousness is closely related to the ability of language and speech. Recursion is less unique since all brains are based on recursive ability. Only when applying this ability with the ability to create symbols to remember and organize them. The possibilities are endless.

Our brain has developed a unique function that, by analogy to computer science, can be called a virtual brain (the analogy is to Virtual Machine). And so the imagination was created. Then all options are open.

Well, the response is requested