A group of scientists from the Weizmann Institute of Science, led by Dr. Guy Shahar from the Department of Immunology, showed that the immune system sends "spies" to the surface of the intestinal walls - immune cells called dendritic cells, which capture the dangerous bacteria and report them to the rest of the immune system

Man shall not live by bread alone. In order to digest the bread, as well as the other food items we consume, our body uses the bacteria living in the intestines. Their number is enormous: these are billions of bacteria, whose total weight in the human body reaches almost two kilograms. Most of them are friendly, and as mentioned, even essential for the proper functioning of the digestive system and other systems in the body. But from time to time, the enemies of humanity mix in between them - disease-causing bacteria, such as salmonella.

In most cases, the immune system knows how to identify the dangerous bacteria and eliminate them even before they cause disease, so we don't even know we've been exposed to danger. But there is a mystery here: how does the immune system distinguish between good bacteria and bad bacteria? I mean, how does she recognize the danger? After all, the cells of the immune system lie within the tissues of the body, while the bacteria reside in the intestinal cavity. Another thing that makes it difficult to identify is that in a normal situation there is a tiny amount of the dangerous factors in relation to the mass of bacteria in the intestines.

A group of scientists from the Weizmann Institute of Science, led by Dr. Guy Shahar from the Department of Immunology, recently shed light on the mystery. As reported in the scientific journal Immunity, the scientists showed that the immune system sends "spies" to the surface of the intestinal walls - immune cells called dendritic cells, which capture the dangerous bacteria and report them to the rest of the immune system - and it sets out to eliminate them. The research was carried out by the research student Dr. Julia Parsha, together with Idan Koren, Idan Milo and Dr. Irina Gurevich from the laboratory of Dr. Shahar, and Dr. Ki-Wook-Kim and Dr. Ehud Sigmund from the laboratory of Prof. Stefan Jung, and in collaboration with scientists from the Mount Seine School of Medicine in New York: Dr. Glausia Portado and Dr. Sergio Lira.

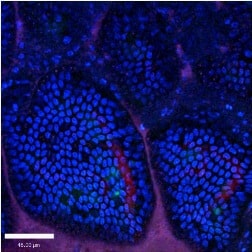

To answer the research questions, the scientists created an innovative system in which immune cells can be tracked in real time using a two-photon microscope in the intestine of a living mouse. It turned out that as soon as the salmonella bacteria adhere to the epithelial cells that line the surface of the small intestine, these cells signal the immune system, and within half an hour dendritic cells, the "spies" of the system, appear on the walls. In film clips, created by viewing under a microscope, it is possible to clearly see how these spies rush to penetrate into the upper layer of cells in the intestinal wall, reach the surface, and send their extensions - the "dendrites", after which they are called - to capture the bacteria.

How do they know how to react specifically to salmonella, and not to the millions of "good" bacteria in the environment? The scientists believe that, unlike salmonella, the beneficial bacteria probably do not stick to the walls and do not harm them.

After swallowing the bacteria, the spy cells rush to report this to the immune system. They activate receptors that lead them back into the intestinal tissue, and from there, through the lymphatic vessels, to the lymph nodes. There they present peptides of the salmonella - in other words, the "body parts" of the bacterium - to the T cells of the immune system, which activate mechanisms to eliminate the salmonella and prevent the infection.

This research may help in the future to develop treatments against irritable bowel disease, which is characterized by inflammatory attacks. Dendritic cells are involved in igniting these attacks, probably due to an overreaction to infection, so a better understanding of their mechanism of action in the gut can help prevent their harmful activity.

In addition, the findings of the new study may contribute to the development of vaccines that can be administered orally, that is, through pills. A lot of effort is being put into the development of this kind of vaccines all over the world, because they have many advantages: for example, it is easier to convince people to take a pill than to get an injection. The vaccine consists of weakened bacteria, but in order for it to be effective, the bacteria must be weakened in such a way that it will not cause disease, but will still activate the immune system. Therefore, it is important to understand how bacteria communicate with the immune system in the gut, and this is exactly what the new study was about.

More about gut bacteria on the science website: