One of the more obscure and missing episodes, although interesting and stimulating, and precisely because of the lack of proper information, is centered around the establishment of a Jewish temple in Egypt, in the midst of the Maccabean revolt, somewhere towards the middle of the second century B.C.

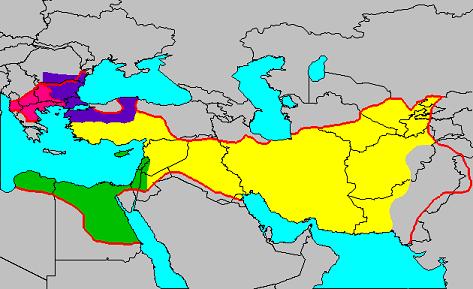

The closest thing I found on the Internet: a map of the Hellenic world in 300 BC, about 130 years before the case described in the article. In green: the Ptolemaic dynasty centered in Egypt and in yellow - the Seleucid kingdom that ruled Syria. The Land of Israel passed several times from hand to hand between the kingdoms. (Avi Blizovsky, website editor)

One of the more obscure and missing episodes, although interesting and stimulating, and precisely because of the lack of proper information, is centered around the establishment of a Jewish temple in Egypt, in the midst of the Maccabean revolt, somewhere towards the middle of the second century BC. The special issue of the affair obviously involves the founding of another temple outside of Jerusalem by someone who was closest to the official high priesthood family, when his motives were, it seems, mainly political and personal.

To understand the significance of the event in question, we must become familiar with the sharp turn that took place in the eighties of the sixth century BC, when the Babylonian army finally commemorated the fall of Judah and "declared", historically, the end of the biblical period, of the First Temple period. The destruction of the first temple was a dramatic and tragic fact. The return of Zion, which followed for about fifty years, marked the end of the royal era in Judah and the beginning of a new, priestly leadership, one that was appropriate for tactical, mythological and pragmatic reasons in the eyes of the new foreign government - the Persians. The priesthood, which in the days of the first temple was secondary to the monarchy and in many cases subject to its dictates, now, from the days of the legendary return to Zion, rose to the height of leadership, and of course drew its power and sanctity from the building of the second temple, its function and its strengthening. This situation persisted with the beginning of the Hellenistic period and gained a special dimension in light of such and other privilege writings that were handed down, for clear political and pragmatic reasons, to the top leadership in Judea. Thus, for example, the Syrian-Greek, Seleucid king, Antiochus III, grants a bill of rights to the Jewish leadership in Jerusalem, as a reward for the assistance it provided during the war against the Egyptian Ptolemaic rule in the country. This Bill of Rights, from the year 198 BC, mainly strengthens the status of the High Priesthood in Judah and at the same time the Temple in Jerusalem. The High Priesthood thus gained the status equivalent, to a certain extent, to a kind of monarchy (monarchy without a crown) and it is no wonder that such power provoked all kinds of intrigues and manipulations among the High Priesthood family, in terms of capital+power+prestige=a lever to corrupt morals. Moreover, the change of foreign rule over Judah - from the Egyptian-Ptolemaic royal house to the Syrian-Greek (Seleucid) royal house - caused natural tensions in the leadership in Judea: on the one hand, the forces supporting Egypt were disappointed, and on the other hand, the supporters of the Seleucids gained strength and enthusiasm. Between these two blocs, debates and confrontations took place, which sometimes escalated into sharp lines. The confrontation between the two blocs was not for heaven's sake. Among the folds of the conflict we recognize political, economic and social motives, and this, as mentioned, from a basic point of departure: whoever weakens the temple weakens society. The cards for this conflict are ravaged by an unexpected source and that is the rebellion of the macabres. This rebellion that broke out in 166 BC, under the leadership of Matthias and Judah, was conducted during a quiet, political and diplomatic confrontation, against the leadership of the High Priesthood (even though the position of the temple was severely damaged following the imposition of the decrees of destruction by Antiochus), which was Greek and had a position supporting the Syrians, in the Seleucids. Even after Judah the Maccabee broke into Jerusalem, purified the temple (164 BC) and appointed new priests, "innocent, objects of the Torah" (as the sources say), the high priests, the Greeks, the supporters of the Syrians, still continued to serve, and this by virtue of the same privilege mentioned above.

In the meantime, and it is not clear exactly when (in the seventies or the fifties-forties of the second century BC) the affair in question begins to unfold - the establishment of a Jewish temple in Egypt at the initiative of the priest Honio ben Shimon. The affair is complicated and complex, both in the chronological-chronological context (after all, each period had its own motives) and in general because it is difficult to pinpoint the factors that motivated Hanio to initiate such a revolutionary and unprecedented move in the history of the temple, the priesthood and Judah as a whole. It is worth noting that no evidence supporting the case was found in the Jewish literature written during that period and even after. Its sources are silent except for the scrolling of the events, quite late in their occurrence, in the writings of Josephus (Josephus Flavius). And precisely there, we can locate, so it seems, the atmosphere on the basis of which the above-mentioned walk of his hunyo was woven. In his first famous composition, "The Antiquity of the Jews", Joseph ben Matthieu describes the courtship "festival" of two Hellenistic, Syrian-Seleucid leaders, who claim the royal crown - Alexander Balas and Demetrius - with the support of Jonathan, the brother of Judah the Maccabee, who succeeded him after Napol Judah in battle (160 BC). Demetrius wins Jonathan's support after he promises him, among other things, the crown of the High Priesthood, in other words giving him internal control over the land of Judah. Demetrius promises Jonathan, as quoted from Yosef ben Mattathias, the following right: "And the high priest will give his opinion on this, that no Jew will have any other temple to bow down to (in) but the one in Jerusalem alone." And here, right next to this text, Yosef ben Matthew "runs away" from the previous theatrical image and opens a window to another image - to the story of the building of the temple in Egypt at the initiative of his servants. The connection between the two events is far from casual and innocent. Demetrius' privilege reflects, it seems, attempts to establish other holy centers outside of Jerusalem (otherwise that privilege has no meaning) and perhaps this is specifically aimed at the rebellious attempt of his followers. It is quite possible to imagine that the privilege was formed and formulated in consultation with the Hasmonean ruler Jonathan, who was aware (from hearsay, of course) of the initiative to establish the temple by his servants in Egypt, and thus sought to insert into the privilege a royal instruction that inhibits any attempt to establish a temple elsewhere . In any case, the picture is becoming clearer, mainly against the background of the message of Hanio to the kings of Egypt, that he intends to build a temple there, identical in shape and dimensions to the Jerusalem temple, and to place in it Levites and priests from his family. And this is to know that the outbreak of the Maccabean rebellion brought about a sharp turn in the chances of continuity of the priesthood at the hands of Beit Hunio. As soon as Jonathan, Yehuda's brother, received the high priesthood, the end came to the dynasty of Beit Honio. As a result, Gomer Honio says to move the sacred center with his entourage and his attendants to Egypt, with the blessing of the Egyptian royal house and probably under his protection, and thus Honio preserves the power of his family and dynasty for better days - the return to Jerusalem. This move was linked to personal motives (as expressed in the words of Ben-Mathetyahu: "He wants to instill glory and a worldly memory for himself") and clear political motives: Beit Honio had a pro-Ptolemaic orientation (supporting the Egyptian-Ptolemaic royal house) from time immemorial, and the possibility cannot be ruled out that Honio He dreamed of upgrading his status and strengthening his family like in the "good old days" - the days of the Ptolemaic rule in Judah (until 198 BC).

Yosef ben Mattathiyo testifies, in relation to this, that his followers were shocked by the recent events that befell Judah, such as the decrees of Antiochus and the Maccabean revolt, which symbolized the end of the traditional priesthood and the growth of a new priestly infrastructure, of the Maccabean-Hasmonean family. No wonder, then, that his son dreams and longs for better days, and in the meantime he ends up saying to build a new temple, in a distant place, to manage and develop it, until the restoration of his family's crown to its old age. The political aspect of the move in question - the establishment of the temple - is hinted at in the "precedence of the Jews", the excited appeal of his supporters to the kings of Egypt in order to win the "green light" from their point of view: the establishment of the temple, in his opinion, will allow the Jews of Egypt to pray for the peace of the Egyptian monarchy and strengthen the feeling of brotherhood among them and the partnership. Honio invokes one of the leading prophets in the period of the First Temple period in order to establish his revolutionary course, and he refers to the prophet Isaiah. Honio confesses that his initiative comes to fulfill Isaiah's prophecy: "In that day there will be an altar to Jehovah in the land of Egypt, because they will cry out to Jehovah from oppressors and he will send them a savior and a great one who will rescue them" (Isaiah 19:XNUMX). This interpretation could certainly have served the revolutionary course of his disciples, considering "but Isaiah foresaw this and prophesied about it".

The political and personal aspect that is hidden behind the conduct of his servants emerges in another composition of Joseph ben-Matthew, referring to the "wars of the Jews". There, the author testifies that during the Maccabean revolt, his son-in-law Ben Shimon fled to Egypt, where he was received with great hospitality due to the tensions and conflict that prevailed between the Egyptian and Syrian monarchies regarding the future of the Middle Area (Judah). Hanio promises the king that he will succeed in enlisting the help of the Jews in his favor and in return he will agree to the foundation of a temple in Egypt and in addition to that - giving Hanio a large and spacious estate, south of the landscape (Moff, Memphis). This passage clearly highlights the personal and political vision of his guardians: to grease the wheels of the Egyptian royal house's renewed takeover of Judah, when, his guardians, he would upgrade his status as a high priest, for him and his family, until the end of time.

It should be noted that the temple of Khunio in Egypt stood in the heart of a large estate that he won from the royal house, and was nicknamed - "Land of Khonio", where hired Jewish warriors, some of whom came together with Khonio from Judea, and whose names were later known in later documents, camped and were stationed there.

Dr. Yehiam Sorek, the historian, Beit Berel

2 תגובות

Regarding Hanuy - it is said in the sources that the matter started with his brother who won the priesthood and Hanuy as revenge came down from Zerayma. See in the Mishna.