A new technique may enable the discovery of Earth-sized planets

Avi Blizovsky

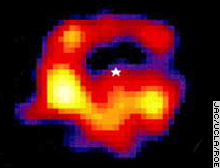

A radio photograph shows a cloud of dust around Epsilon Eridani, one of our stellar neighbors

A new method that will make it possible to locate the existence and location of small planets orbiting other stars has made possible the discovery of a world with a mass about one-tenth that of Jupiter.

The new technique, developed by a team at the University of Rochester in New York, may in the future detect small planets, perhaps even the size of Earth. This is in contrast to most of the stars discovered which were more similar to the gas giants of the solar system.

The planet orbits Epsilon Eridani, about ten light years from Earth. It is the lowest mass planet discovered so far. It is also very far from its sun, about the same distance as Pluto from our sun.

"We are very excited because this opens up the possibility of finding planets that we would not have been able to discover just by observing the main star of the system." says physicist Alice Quillen, the lead author of the article published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Almost all of the hundred known planets outside the solar system were of two types - some of them were discovered while passing between us and their sun and dimming its light in a regular pattern. Other planets were discovered due to their gravitational influence on the main star. Those with the closest mass and which orbit their sun in a close orbit may sometimes distort the star's orbit so that they can be located by this distortion.

In contrast, Quillen and her colleagues Steven Thurdike discovered patterns of dust around Epsilon Eridani, a young star still surrounded by a ring of dust, as was the case in the young solar system. "Not all young stars have a large concentration of gas surrounding them, but those that do, such as Epsilon Eridani, can show us bulges in the dust field. These gaps may be planets.

In the astronomical community, opinions are divided as to what was found. According to Artie Hayes, the director of the observatory in Thuringia, Germany, he also anticipated the possibility of detecting planets in gas clouds. However, since it is an indirect way, it is necessary to confirm the existence of these planets by other methods to be sure.

Debra Fisher of the University of California, Berkeley welcomes the new technique but notes that stars with a dust disk like Epsilon Eridani are rare. Another astronomer from Berkeley, Steve Watt, is also not enthusiastic: "It looks like a long shot. It is very difficult to get from a theoretical model and locate a small point on the disk, to a message about the detection of a planet. There are many possibilities to explain these bumps in the dust cloud without interpreting them as planets."