About 80 small geysers erupt in the Atacama Desert in Chile, and they provide a similar opportunity to study their underground mechanisms. Geologists loaded with temperature and pressure sensors, GoPro cameras and a host of other accessories examined one of these geysers

In Yellowstone National Park, the "Old Faithful" geyser fascinates and entertains tourists with its repeated eruptions. But due to its popularity, it is closely guarded: the government restricts access to it by curious scientists and the experiments they are allowed to conduct among it. However, at least 80 smaller but equally punctual geysers erupt in the Atacama Desert in Chile, and they provide a similar opportunity to examine their underground mechanisms. Geologists loaded with temperature and pressure sensors, GoPro cameras and a host of other accessories examined one of these geysers, which they named "El Jefe" (The Boss). In their review, which lasted five days, more than 3,500 eruptions occurred, one every 132 seconds. And what was the result? The most detailed collection of data yet on this explosive choreography of water and steam.

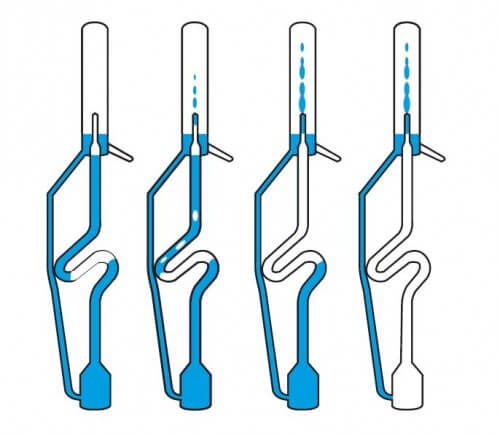

Al-Hefe's eruptions are more regular than many other geysers, but the plumbing is similar: a deep underground reservoir of water feeds a narrow shaft leading to the surface. Heat from the Earth's core reaches the reservoir, and steam bubbles rise up the shaft until they are trapped in a small side chamber: a "bubble trap". When enough steam accumulates in the trap, it is ejected and raises the water level in the geyser's upper shaft. Eventually, the bubbles that escaped the trap heat the water in the shaft to boiling, and a full eruption occurs: the low pressure of the boiling water at the top of the water column starts a chain reaction that moves downward, lowering the boiling temperature of the water at the bottom, until steam and hot water from the entire column splashes up At once. (These stages, followed by a recharge stage, where the water seeps back into the reservoir before another cycle begins, are shown in an illustration of the laboratory model the team created.) The observations were published in February 2015 in the Journal of Volcanic and Geothermal Research.

Measurements from several different depths will be useful for understanding the geyser cycle and the boiling patterns in it, says Michael Manga, a geologist from the University of California at Berkeley who participated in the study. Other studies have documented only pressure or only temperature, but both are necessary for a deeper understanding of how heat travels through subsurface water. Steven Ingebritsen, a researcher at the US Geological Survey, is interested in what this more complete picture of the geysers can teach geologists about geothermal phenomena such as volcanoes, phenomena that occur mainly below the surface of the ground and are very difficult to study, because the devices may melt with heat, for example. The same underground magma flow drives both types of eruption. "They lowered the sensors as deep as possible," says Ingebritsen. "But the question arises as to what happens at greater depths."

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

2 תגובות

Maybe a video, or a link to the original article

Thanks for the interesting article.

Some pictures with the possibility of enlargement or links, there were definitely

give a different dimension to understanding the phenomenon. Also numerical data

And measurement results would be additional.

Thank you anyway.