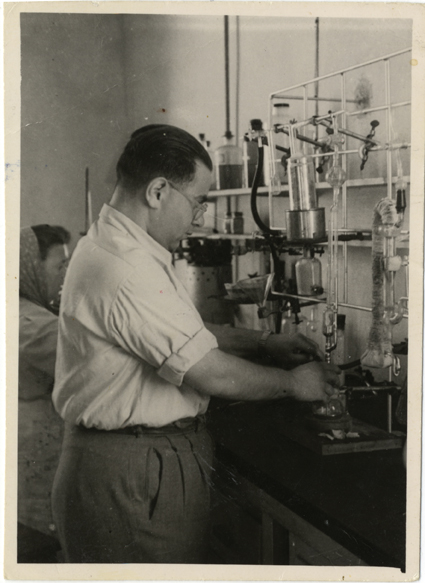

Prof. Shalom Sharel was accepted as a research student at the Ziv Institute in 1943 and engaged in the development of anti-malarial drugs for the British Army in India and thereby founded the Israeli pharmaceutical industry

"I was interested in the promising topic: 'How different chemical substances cause skin cancer - a phenomenon that has just been discovered - and if it is possible to intervene in this process to prevent the development of the cancerous tumor,' says Prof. Shalom Sharel, who was accepted, at the age of 23, as a research student at the Research Institute on Named Daniel Ziv in 1943.

"The encounter with the scientific being at the Ziv Institute was a kind of revolution for me. I came from a harsh academic world, and suddenly I entered a free and friendly world of high-level researchers, who talk to you at eye level. The high scientific level that I experienced immediately upon entering the institute created a feeling of a wonderful scientific 'desert'. This is reflected in the many scientific publications that the institute's staff produced, the quality of which gave the institute prestige in the scientific world, and contributed to the construction of the infrastructure on which Israeli science grew and flourished.

"The institute was wonderfully planned and organized to fulfill its research missions. It had an excellent scientific library, a team of excellent laboratory technicians, and a microanalytical laboratory - the first of its kind in the Land of Israel - which served not only the institute's scientists, but also other scientists from Israel and abroad. The institute was research-oriented in the natural sciences, and made available to the researchers first-class ancillary services, such as glasssmiths and instrument-building workshops, which allowed the research scientist to focus on his scientific work.

"When I was at the institute, I opened up to a wide world that I had not yet known. Suddenly I came into contact with distinguished guests from abroad, and I was exposed to the institute's senior scientists who carried with them the spirit of the great world. The horizons of interest of the institute's scientists were far from the everyday Israeli existence.

"To some extent it was a fascinating bubble - a world that stands on its own, a little distant from the existence of the Land of Israel. The institute had the feeling of huddling in a kind of royal palace, which stemmed from the quasi-royal aura that enveloped Chaim Weizman, who at the time served as president of the World Zionist Organization. He used to arrive at 10 in the morning in the "Ford" car

His black, which brought him to the entrance of the building, went up to the second floor, where was his laboratory which also served as his reception room, where he received many high-ranking guests, including senior British officers. The scientists would go up to him from time to time, but the ongoing research was directed by Ernst Bergman, the scientific director of the institute. Sometimes I was asked by Dr. Weizman's administrative assistant to guide visitors and visitors at the institute.

The institute is at war

"During the Second World War, Chaim Weizmann came to the disposal of the British war effort. At one point, the allied armies suffered from a severe shortage of drugs that were needed in the tropical combat zones (Burma and India), especially anti-malarial drugs.

The well-known drug, quinine, was produced from a plant that grew on the island of Java, which was occupied by the Japanese. In the building then called the Wolff Institute (today the building named after Daniel Wolff), which stood near the Ziv Institute, a semi-industrial facility was established for the production of Atbarin - a German drug that was a synthetic substitute for quinine. This was an important contribution to the war effort, and the drugs were sent directly to India. The work was directed by Dr. Ludwig Taub, who brought with him from Germany the knowledge necessary to produce the drug. Sometimes I volunteered to help Dr. Taub Calburnt. When I would leave the building people were scared of me because the yellow powder of the medicine covered my face. The Ziv Institute contributed at that time to the development of the local pharmaceutical industry in the Land of Israel. This momentum of development is evident in the Israeli pharmaceutical industry to this day. "The scientific director of the institute, Ernst Bergman, was very active in the war effort. Through the connections that Haim Weizman made with British industry, Bergman was sent to England, where he helped develop new processes for producing artificial rubber. During the war there was a severe shortage of rubber, because the source of natural rubber - like that of quinine - was in the islands conquered by the Japanese. In addition, and secretly, probably without Haim Weizman's knowledge, the two Bergman brothers contributed,

The elder, Ernest, and the younger, Felix, for a war effort of a different kind - assisting the 'Yishuv' in developing infrastructure for the country's defense industry on the way. Felix Bergman, with his characteristic discretion, provided Hagana with valuable advice in various fields. This was kept a secret so as not to embarrass Dr. Weizmann in the trusting relationship he cultivated over the years with the British Mandate authorities.

"During the war, the institute was practically isolated from the world. In order to overcome the disconnection from scientific innovations in the world, lectures, a kind of seminars, were organized at the institute, in order to keep up to date and avoid 'fossilization'. I gave the first lectures on the structure of hemoglobin and all those discoveries that revolutionized biochemistry - which at that time began to overflow with many works and findings. British officers who were scientists were also invited to lecture. "The war also gave birth to surprising international connections: a Jewish scientist named Prof. Alexander Schoenberg used to come from Egypt several times a year, who was appointed as a professor of chemistry at the first university in Egypt named after King Fouad, in Cairo, after he was expelled from his position in Nazi Germany. In Egypt, no equipment was made available to him, and therefore, in his distress, he began to investigate the possibilities of utilizing the sun's radiation to accelerate various chemical reactions. Prof. Schoenberg used to come to Felix Bergman at the Ziv Institute to analyze for him the multitude of compounds he brought with him, as well as for the purpose of discussing the results. After the war, Prof. Schoenberg returned to the University of Berlin, crowned with fame due to his achievements in photochemistry.

"Ernest Bergman, Dr. Weizmann's right-hand man in the scientific management of the institute, was known in Germany, before the war, as one of the three shining stars that walked in the sky of German chemistry. With the rise of the Nazis to power he was expelled from Germany. He developed original synthetic methods for the preparation of substances that contributed to the understanding of the relationship between chemical structure and biological activity.

"Bergman was a walking legend. He is endowed with tremendous intellectual energies. He was very active and published articles at a rapid pace. He had an excellent visual memory. First, every chemical experiment begins with careful planning and a comprehensive review of professional literature. But Bergman had shortcuts. He knew how to locate the necessary information and say precisely not only which article it was, but also which page. His capacity for work was extraordinary.

"The institute was surrounded by orchards, and during breaks I would go out, and a few meters away from the building I would reach out to pick some oranges. Between the institute and the agricultural experimental station was an empty lot, and about 200 meters north of it was a concrete building called 'the club', where we used to eat. Sometimes you could hear concerts or lectures there.

Pushkin in Jerusalem

"Haim Weizman's sister, Dr. Anna Weizman, 'Anushka', also worked in the organic chemistry laboratory on the ground floor of the Ziv Institute. She was interested in active substances in medicinal plants. After I returned to Jerusalem, I continued to meet with her when she would come once a month to a literary circle at the home of Dr. Leonid Dolzhansky, the founder of research into the chemistry of cancer at the Hebrew University (he was shot to death by Arabs in 1948 in the Mount Scopus caravan that made its way to the home of the besieged hospitals). Scientists and intellectuals met there to read together classical Russian poetry, especially Pushkin. It was hard to get books in Russian then, and everyone came equipped with their own books. Anushka Weizmann knew Russian very well, and took every opportunity to use the language.

"Prof. Moshe Weizman, who was my chemistry teacher at the university and later the director of the department where I worked, also came to these meetings. When I started teaching organic chemistry at the university, he organized a meeting for me with Dr. Haim Weizman to tell him about my work. Being a student at the Ziv Institute, I only had random encounters with Dr. Weizman, and it was a great honor to travel to his home in Rehovot. He could no longer see well, but he was alertly interested in everything that happened in the research laboratories.

"When I returned to Jerusalem, I also renewed my ties with the two Kachelsky brothers, Ephraim and Aharon, with whom I was still friends during my studies at Mount Scopus. Both were considered 'stars' and objects of admiration. Aharon Katzir was my direct commander in Hamad, where I served in the War of Liberation. During the siege of Jerusalem, Aharon proposed that a method be developed to turn flour into nitro-starch - an explosive required for the defense of the city. We started working on this task, but in the end, because of the siege, we used flour to bake bread." About this it is said "and his swords are drawn".

personal

After completing his studies in biochemistry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Shalom Sharel prepared his doctoral thesis, on "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as carcinogens", at the Ziv Institute, under the guidance of Prof. Felix Bergman. Felix, like his brother, fled Germany when the Nazis came to power, and later became a professor of pharmacology. The Ziv Institute did not award academic degrees. Therefore, in this sense, Sharel was registered as a research student at the Hebrew University, under the guidance of Prof. Moshe Weizman.

After receiving his doctorate in 1946, Sharel was appointed an assistant in the organic chemistry department at the Hebrew University, headed by Prof. Moshe Weizman, and since then he has not left the university. Over the years, he founded and managed the department of medicinal chemistry at the Hebrew University's School of Pharmacy and Hadassah, and carried out basic and applied research in many areas of organic chemistry. He served as the first president of the "Israeli Chemical Society", organized several international chemistry conferences in Jerusalem, was editor-in-chief of the scientific quarterly Israel Journal of Chemistry, served as vice-president of the European Federation for Medicinal Chemistry, and also founded the "Israeli Association for Medicinal Chemistry ".

For the article on the Weizmann Institute magazine website with additional photos