T cells are essential for the regeneration processes of nerve cells in the brain, according to a study carried out at the Weizmann Institute

The Institute

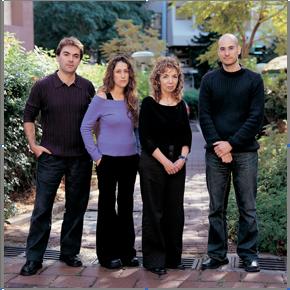

From right to left: research student Yaniv Ziv, Prof. Michal Schwartz and research students, Nega Ron and Oleg Butovsky.

Regenerative cells in the cells of the immune system contribute to maintaining the ability to perform learning and memory processes, as well as to the regeneration processes of nerve cells in the brain throughout life. A group of scientists, led by Prof. Michal Schwartz from the Department of Neurobiology at the Weizmann Institute of Science, described this new concept in an article recently published in the scientific journal "Nature Neuroscience".

For a long time, scientists believed that a person is born with a fixed amount of nerve cells in his brain, which gradually die over time, and cannot be regenerated. But in recent years, several research groups, from different parts of the world, have published studies according to which new cells are nevertheless formed in certain areas of the brain, including one of the areas involved in certain learning and memory processes (hippocampus). This process of creating new nerve cells occurs especially after exposure to an environment rich in environmental stimuli, as well as following physical activity. The function of these new cells is still not clear, but one of the assumptions is that they are designed to preserve and renew the brain's abilities. One of the main questions that remains open is: how does the body transmit signals to the brain instructing it to increase the formation of new cells. Weizmann Institute scientists now offer an explanation for this phenomenon.

The new explanation is based on a new concept of the role of the immune system in the "space of action" of the central nervous system, which includes the brain, the spinal cord, and some individual nerves such as the optic nerve. In fact, for many years the brain was considered a "forbidden city" for the immune system, which was perceived as a factor that could harm the complex and dynamic networks of nerve cells. An even greater danger has been attributed to the presence and activity of autoimmune cells in the brain. These cells (unlike the other cells in the immune system, which attack foreign invaders and disease-causing agents), recognize the body's own components, a process that, if it occurs without appropriate control, may cause the development of an autoimmune disease, such as multiple sclerosis.

Thus, in the past, scientists who discovered the presence of autoimmune cells in a healthy central nervous system attributed this to the body's failure to eliminate these unwanted cells. In contrast, the scientists of the Weizmann Institute of Science, led by Prof. Schwartz, believe that autoimmunity in itself is not harmful and even necessary, and that it is a question of "good measure". Uncontrolled autoimmunity can indeed be harmful, but when it exists to the right extent, the same phenomenon itself may actually be beneficial and help delay degenerative diseases such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, glaucoma, ALS and neurodegeneration due to stroke, or any damage to the central nervous system.

Prof. Schwartz's research group previously showed that the cells of the immune system (T cells), which recognize components of the central nervous system, regulate the immune response against toxic substances secreted in damaged areas, and are involved in neurodegeneration processes (a phenomenon known in cases of head injuries, as well as after Stroke).

In the current study, the scientists showed that the same immune cells that recognize self-proteins (autoimmune cells) also help in central processes that take place in a healthy brain, such as learning and memory. They hypothesize that this assistance is expressed by encouraging the formation of new brain cells in the hippocampus area, which serves to create new memories of certain types. The research group that carried out this study includes, in addition to Prof. Schwartz, the post-doctoral researcher Dr. Jonathan Kipnis (currently in Nebraska), and the research students Yaniv Ziv, Nega Ron and Oleg Butovsky. Dr. Hagit Cohen from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev worked together with them. Several groups of researchers previously reported that in the brain (hippocampus) of rats living in an environment rich in stimuli, more new brain cells are formed compared to the amount of new cells formed in the brains of rats living in a normal environment. The current study links this phenomenon for the first time to the presence of cells of the immune system in the hippocampus. To examine whether the presence of cells of the immune system, including T cells, is indeed essential for the regeneration of cells in the brain, the scientists tested mice with a damaged immune system. It was found that in the brains of these mice, much fewer new nerve cells were formed. In addition, it turns out that when T cells taken from a normal mouse are injected into mice with a damaged immune system, the amount of new nerve cells created in the brain can be increased, almost to the level typical of a healthy mouse. From this the scientists concluded that T cells are essential for the regeneration processes of nerve cells in the brain, and that repairing the immune system can compensate for this lack in the brain. Another series of experiments was performed with the aim of characterizing the specific T cells that enable the creation of new nerve cells. It was found that in mice that were genetically modified so that all the T cells in their body recognize components of the nervous system, more new nerve cells were formed compared to normal mice. These mice also performed better on learning and memory tasks compared to normal mice. Conversely, in mice whose T cells in their bodies do not recognize any components of the nervous system, fewer new nerve cells were formed, similar to mice with a damaged immune system. These mice also had difficulty performing learning and memory tasks. Prof. Schwartz: "We believe that auto-immune T cells may help the organism realize the full potential of its brain. The findings of our research show that the body transmits messages to the brain, through the immune system, that regulate, among other things, learning and memory abilities. It is also possible that memory loss that occurs at advanced ages is due, at least in part, to the weakening of the immune system, or alternatively to the loss of activity of those cells responsible for brain maintenance. If this is indeed the case, it is possible that our discoveries may contribute, in the future, to the development of new ways to treat memory loss resulting from aging."

pressure cabinet

T cells that recognize self proteins in the central nervous system, in mice, reduce mental damage resulting from events reminiscent of post-traumatic syndrome. Conversely, mice lacking these cells are more damaged in similar critical situations. These findings arise from another series of experiments carried out by Prof. Schwartz's research group, and recently described in the scientific journal Journal of Neurobiology.

Prof. Schwartz says that these findings will lead, perhaps, in the future, to the development of vaccines based on T cells, which could help those suffering from post-traumatic syndrome.

Yadan Brain - Research of serious diseases

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~432739184~~~238&SiteName=hayadan