The first part of the article, which deals with Comte de Buffon and his theory that tried to unify the entire bilogy

The spontaneous formation in the 17th century

The pattern of spontaneous formation in complex creatures came to an end towards the end of the 17th century. Francesco Redi proved in his simple experiments that flies are not formed from rotten meat, thus opening the door to other studies that showed that many other insects are also not formed from lifeless matter. More and more animals were deleted from the list of recipes for spontaneous formation, and by 1680 it seemed that the scroll had been sealed.

The year 1680 is a turning point in the history of biology. This was the year in which Antony van Leeuwenhoek first proved the existence of bacteria and protozoa. The bacteria and protozoa are so small that they cannot be seen by the human eye. Until 1680, humanity was not aware of their existence at all, and Leeuwenhoek's discovery was initially met with suspicion and derision. However, when Leeuwenhoek managed to prove their existence, a new world opened up to the science of biology. This world was rich with life that humans never suspected existed.

Now that those tiny creatures were discovered - the animolecules, as Ivanhoek called them - the scientific world was forced to reconsider the idea of spontaneous formation. These creatures were so small that it was hard to believe that they lay eggs, or give birth to even smaller offspring. Many scientists have decided that the animal molecules (or microorganisms, as they are called today), are created from inanimate matter. That is, the theory of spontaneous formation is true only for those microorganisms.

How can this be proved?

Van Leeuwenhoek himself documented that it is possible to 'create' micro-organisms with a very simple method. He took hay and soaked it in water inside a bottle. Over the next several days, the water became increasingly cloudy. When Leeuwenhoek observed water through the lens of the microscope, he saw extremely large amounts of animal molecules floating in solution. Although each of the individual molecules could not be seen with the naked eye, they were running in such large quantities in the water that the water appeared cloudy. Although Leeuwenhoek himself believed that the animal molecules did not form by themselves, other scientists accepted the experiment as proof that the animal molecules were formed from wet hay.

Today we know that hay contains a large amount of bacteria and protozoa, as well as many spores of bacterial strains that are resistant to heat to one degree or another. When the hay was immersed in water, the various microorganisms moved into the water and multiplied there until the solution became cloudy. However, this was not clear at all and mainly to those scientists who were engaged in the study of the animal molecules.

The forgotten article aside

Thirty years after the discovery of the animolecules, a French scientist named Louis Joblot tried to disprove the spontaneous formation. First of all he tried to prove that the animal molecules are not formed from hay-water. The experiment he carried out for this purpose is reminiscent of Reddy's experiment in its simplicity. Joblot dipped hay in water, then pumped the water into a glass container. The glass container was boiled well, then the water was poured into two separate bottles. One of the bottles was kept completely sealed, so no air could get into it. The other bottle was left open. After a few days the water in the open bottle became cloudy, and many microorganisms were found in it. The water in the sealed bottle, on the other hand, remained clear and clean, and no sign of animolecules was detected in it. To prove that the water itself is still capable of containing life, Joblot opened the sealed bottle and showed that after a few days the water was filled with animal molecules.

In this simple experiment Joblot proved that life could not arise by itself in the boiling solution. An additional component that came from the air was needed to allow the microorganisms to grow in the solution. Joblot did not know what that other component was, but today we are aware that there are many bacteria floating in the air all the time. Even on our skin are billions of microorganisms, and biologists handling cell cultures know that they must wear rubber gloves on their hands. If they do not do so, the bacteria on the skin of the hands may fall into the sample and contaminate it. The purpose of the rubber gloves is to protect the cell cultures from the bacteria found on the skin of the hands.

Similarly, when the bottle is left open, the microorganisms in the air can enter it and contaminate the solution.

Joblot did not know that bacteria also exist in air, but he concluded from his experiment that air is needed to contaminate a solution that is clean of microorganisms. Unfortunately, he was unable to design an experiment that would determine whether there are microorganisms in the air, or whether it is some other property of the air that allows the molecules to form by themselves in solution.

Joblot's experiments were not widely distributed and it took a long time for them to be translated into other languages. As a result, many scientists of Joblot's time had not heard of the experiment or its results. Even when other scientists repeated his experiments, they reached conflicting results. Remember, hay contains many species of bacteria, heat resistant spores, fungi and protozoa. Each of those microorganisms reacts differently to heat. Therefore, the results of the experiment can vary greatly depending on the degree of sealing of the bottle, and the time and method of heating the solution.

The idea of spontaneous formation in microorganisms continued to be widespread and accepted in the scientific community and worldwide. Hieronymus Percustorius proposed already two hundred years ago that diseases are caused by living organisms, and that these organisms can pass through air and water. But what's the point of killing those organisms, when they are being regenerated all the time? And so the scientific world hesitated and procrastinated. Spontaneous formation has eluded bacterial researchers, and cures for diseases still do not exist. And as if to complete the story, a couple of scientists arrived - Comte de Buffon and John Torbanville Needham - and ended up proving once and for all that spontaneous formation is valid and exists.

The little giant - Count de Buffon

Count Georges Louis Leclerc de Buffon was one of those rare geniuses who had their hand in everything. He was well versed in all types of science at the time, and devoted half of his life to trying to document all biological knowledge and include it in one vast theory. His height did not exceed 150 centimeters, but he left a huge mark in the world of science in Europe as a whole. His name became known all over France - due to the eloquence of his explanations, the passion of his words and the enormous contribution he made to his homeland with the help of science. Buffon, in fact, led to the opening of a new era in the natural sciences, which is not ready to accept supernatural or religious explanations as an answer to the questions that nature presents.

If they had told the young Buffon's teachers that he would become the most popular scientist of his time in France, they would surely have laughed out loud. Similar to other geniuses, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Albert Einstein, Buffon also did not succeed in his studies at school. His grades were average at most, and only in the mathematics subject did he show any talent. He expressed to his father his desire to specialize in the field of mathematics, but the strict father refused to comply. He himself was a judge in France, and wanted his son to follow his own path and specialize in the field of law and jurisprudence. Buffon tried to please his father and started studying law at the age of 16. Although he tried to focus on his studies, he continued to be interested in mathematics and discovered Newton's binomial (an important formula in mathematics, which allows developing powers of the sum of two terms).

At the age of 19, Buffon finished his law studies, and against his father's wishes he transferred to the University of Angers to study mathematics. His curiosity did not allow him to focus on just one subject, and he occupied himself with research in botany and medicine as well. These studies were abruptly interrupted in 1730, when he got involved in a duel, and was expelled from the university. He spent the next two years traveling through Europe, during which he also visited Italy and England. During the journey, Buffon studied nature in those countries and was impressed by the philosophical positions of Isaac Newton, who stated that there are mechanical forces that control the movement of all things. This mechanical force is known to us today as gravity, but for the young Buffon, gravity represented pure science: finding laws for nature that do not require the existence of God. In his greatest work of all - the history of nature - he will try to find similar laws that supervise the creation of living things from inanimate matter.

At the age of 25, Buffon finally returned to his hometown, after he learned that his mother had died and his father was about to remarry. The source of most of the Buffon family fortune was the late mother. When the mother died, in her will she left most of her wealth to Buffon the son, and not to his father. The father tried to take control of the inheritance and remarry, but Buffon returned at the last moment, and used the knowledge he gained in law studies to fight his father for the inheritance. Despite his father's anger, to which he was already accustomed, he managed to receive the Buffon estate as his legal inheritance, and has made his home there ever since.

In 1734, at the age of 27, Buffon was admitted as a member of the Royal French Academy of Sciences, after submitting papers on mechanics and mathematics to the academy. In later years, he translated Newton into French, thereby allowing the public in France to be exposed to Newton's groundbreaking ideas in mechanics and applied mathematics.

The rich and young Frenchman began to make his mark in Paris and in its scientific and political circles. During these years he was recruited by one of the ministers of the parliament, who tried to restore the prestige of the French navy. The minister tried to improve the construction of the warships, and asked Boffon to investigate the degree of strength of young trees in order to aid in the craft. Buffon vigorously approached the craft, and his diagnoses on the strength of young trees and the right time when they should be felled remained valid until the 20th century [A].

In 1739, a new chapter in Buffon's life opened, when he was appointed director of the royal gardens. In the fifty years that remained to him, Buffon turned the royal gardens into an important scientific museum and center for the study of nature, whose sound went out all over the world. Trees and plants, animals and fossils, all were brought to the royal gardens and found their home in them at that time. The Royal Gardens became the most important institute in France for the study of botany, zoology, chemistry and mineralogy.

A Lifetime Achievement: The 'History of Nature'

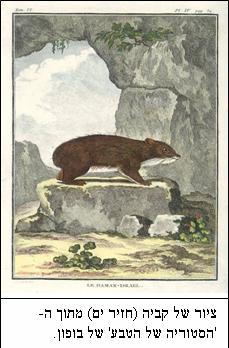

Now that his academic and financial future was assured, Buffon approached the most ambitious task of his life. He decided to unite all the natural sciences in a series of volumes called 'Histoire Naturelle' - the history of nature. In this series, which ended only after his death and included 44 volumes, Buffon described all the mammals, birds, reptiles and minerals that were known to science, accompanied by colorful drawings and equally colorful descriptions. Buffon believed that it was difficult to get people to read a boring encyclopedia, composed of entry after entry. On each subject he added amusing and interesting anecdotes, thus turning the encyclopedia into a reading book for the general public. The encyclopedia tried to answer all the questions of nature in a material way and based on the facts that were known to science at that time.

Although Buffon's colleagues in the natural sciences turned up their noses at Buffon's pictorial and poetic explanations, they could not deny the enormous popularity that the encyclopedia gained.

The general public in France flocked to the enormous literary work, and it is estimated that it is the second most famous work of the French Enlightenment period, after Diderot's encyclopedia. The work was also translated into many languages, and Buffon became the best-known scientific writer of his time, side by side with Rousseau and Voltaire. [B]

Although Buffon did not specialize in a particular field in the experimental sciences, he became familiar with the works of the scientists of his time and tried to create theories that would unify them.

In his books, Buffon proposed that the solar system was formed due to the impact of a large asteroid on the sun. The enormous force with which the asteroid hit the Sun caused molten material to erupt from it, cool in space and become the planets. This theory was unique in its time because it attributed the creation of the earth to physical forces, when even Newton believed that the planets were created in their orbits around the sun by the power of divine providence. This opinion of Buffon was actually disproved only in the 20th century, but its real power was in removing the 'divine factor' from scientific thought.

From the idea that the Earth was formed from a mass of molten material that cooled slowly in space, Buffon came to the revolutionary conclusion that the age of the Earth is 75,000 years, relying on the time it takes for iron to cool. The official position of the church was that the world was created 6000 years ago, but the leaders of the church preferred not to quarrel with Buffon on this point. At the same time, when Buffon came out with a statement that the flood never happened, the church had to respond. He was accused of blasphemy by the Catholic Church in France, and his books were put on the stake. To appease the church, Buffon flexed his stiff neck and added a preface to each of his books, in which he denied their content. Buffon also felt obliged to write this introduction in his colorful style. It seems that more than this introduction denies what comes after it, it is used to snot in the church, as can be seen in Principles of Geology:

"I hereby declare that I had no intention of contradicting the Holy Scriptures, and that I believe with all my heart in the creation of the world as it is described in those Scriptures. I believe that the world was created as described, and in the chronological time attached to it. I hereby abandon everything in my book that describes the creation of the Earth, and in general everything that may not be in line with Moshe's version."

A new theory is born

Buffon entered the story of spontaneous formation due to the theory he came up with, which tried to unify all of biology under one umbrella. He claimed that there are 'organic molecules', capable of joining together to form a living body. In order for them to know the shape of the body they must create, there are 'patterns' according to which the molecules are organized and form the living body in the correct way. Buffon tried to describe the force that pulls the organic molecules together as similar to the Newtonian force of attraction between two masses. He called this power 'the plant power'.

According to Buffon, the organic molecules exist in all living things: plants and animals. When an organism dies, the organic molecules leave its body and reassemble in some form forming a living body. In this way, Buffon explained the formation of worms in corpses, and this is how, according to him, micro-organisms were also formed in water that had undergone 'hay immersion'. Organic molecules from the hay fell into the water, and recombined in the pattern of the animolecules that was in the water.

Today we understand better the way of creating life, and can see that Buffon's approach was not fundamentally far from reality. We know today that the 'template' is actually the DNA inside the cells, and the organic molecules are the proteins that are created according to the instructions encoded in the DNA. Buffon's big mistake was assuming that the organic molecules combine themselves into living bodies. In fact, living things can only be created from other living things, either by reproduction or by self-division.

Except that theory is separate and proof is separate. Buffon knew very well that as long as there was no conclusive proof of the possibility of spontaneous formation, his theory would not be accepted by the scientific community. In order to confirm the theory he built, Buffon decided to consult a lesser-known scientist from that time, whose name was John Turbinville Needham, about whom we will expand tomorrow.