Nor was the medical establishment's treatment of Lister any better than that of Semmelweis, but his determination was stronger.

The previous part of this chapter ended with the publication of Lister's excellent results in the most prestigious scientific journal of medicine. But as we have already learned from Zemmelweis's story, the medical world does not immediately open up to far-reaching changes. At first Lister's method was openly ridiculed. James Simpson claimed that phenol had been used in the past to dress wounds, but without noteworthy results. Unlike Zemlweiss, Lister kept his cool and ignored the ridicule of his detractors (later it was also revealed that Simpson had a hidden agenda, as he was trying to develop a competing technique). He continued to publish the articles in The Lancet about his anti-sepsis method and the success he had in the various cases in which he applied it.

It is possible that the introduction of the new technique would have been delayed, if the Franco-Prussian war had not broken out in 1870. At that time, the human race succeeded in perfecting weapons of war capable of inflicting mass casualties, such as cannons. The military surgeons of both sides had to perform thousands of amputations on the battlefield and in the hospitals. The severe infections that attacked the patients caused the death of many soldiers, and both sides looked for a way to fight the inevitable infection. The anti-sepsis technique that was published for the first time in 1867 attracted their attention, and with the beginning of the war, Lister's lecture rooms were filled to capacity with Austrian and French surgeons and doctors, who carried the word of the method to their countries.

The one-eyed reader may ask himself why the British doctors were absent from Lister's lecture rooms. As the proverb says, there is no prophet in his city. Precisely in England itself, Lister's homeland, the antisepsis did not succeed. The English doctors and surgeons were not convinced by all the microscopic evidence that Lister brought to the presence of microbes - those tiny pollutants - in the wounds. The main blame for this was probably found in the teaching method of the English doctors, which neglected the principles of research and science and concentrated on learning techniques for body fusion. If we summarize the problem simply, the English doctors were brought up to be 'technicians of the body', and not scientists capable of independent research.

Lister also carried some of the blame on his shoulders. His lectures seemed more like lectures in pathology and microbiology than lectures in medicine. He would bring chemical bottles and petri dishes with him, and would demonstrate under the microscope the presence of bacteria in solutions and pus. The British doctors, who throughout their university studies had never looked through the microscope more than once or twice, could not understand and accept the wonders he discovered under the microscope lenses. In France and Austria, on the other hand, scientific education in universities was at a much higher level. The students were trained in the use of the microscope and the other laboratory tools, and when they received the coveted degree they were more open to understanding and accepting the proofs and testimonies in Lister's hands.

It is possible that the public in England felt the scientific revolution taking place around them. This was certainly the case when Lister was invited to his victory tour in Germany in 1875. On this trip, Lister visited hospitals throughout the country, and saw with his own eyes the changes that had taken place in them according to the anti-sepsis method. In the eyes of the French and Austrians, he was like a god who brought the gift of life to many of their people. The public in England was certainly surprised when he won the great honor and was chosen to be the president of the surgery session at the International Medical Conference in Philadelphia, a year later. But the English doctors refused to accept his methods, and even in 1890 the British surgeons were laughing among themselves about Lister's strange ideas.

That arrogant grin cost the treated audience dearly. The ideas they refused to accept included the use of phenol bandages to disinfect wounds, washing the surgeons' hands and tools with phenol in order to prevent infection of the wound, and the development of sterile suture threads that self-degrade within the wound (and do not require reopening the surgical site in order to pull out the threads after recovery). While these modern and effective techniques were applied all over Europe, in England the same ominous sign still hung on the door of the operating room: Abandon all hope, ye who enter. This phrase, engraved on the gates of hell, continued to reliably reflect the chances of patients recovering after complicated surgery in England of the time.

Zemlweiss and Lister, 'world-facilities', both acted out of noble motives to improve the quality of people's lives and prevent unnecessary deaths. Both were motivated by compassion for their fellow humans, and the desire to stop the pain and suffering in the world. Like Zemlweiss, Lister was unable to close his eyes to the human suffering around him, and felt obliged to bring his new method to England as well. The English were not ready to accept the anti-sepsis idea from the diaspora, and Lister was right to leave the safe university in Scotland and move to London in the hope of working from within and spreading his method within England itself.

When the decision took root in his heart, and was published publicly, Andromulusia Rabiti hid in the university where he researched and taught. Many faculty members begged him not to leave Scotland, where he spent 24 years of his life, met the woman he loved and produced his most important research. Over 700 students signed a petition wrapped in luxurious leather, in which they solemnly petitioned him to stay at the university. We learn about the love and respect they acquired for him in Scotland from Watson Cheney, one of his students, who tells of his reaction when Lister asked him to join him in London:

"To go with Lister to London! I couldn't believe my ears. Of course I will go with him to London, or anywhere else!”

How different he was from Zemlweiss, a voluntary outcast and friendless! It seems that they cannot be compared at all, but both he and the Austrian doctor acted according to their hearts. Despite the entreaties, requests and pressures exerted on him by the whole of Scotland, Lister felt morally obliged to transfer his teachings to his native land. In 1877 he took the big step, and began his crusade in London, he and his wife with him.

The years in England

It is highly doubtful whether Lister foresaw all the hardships that faced him in the capital city. The students in the lectures he gave did not understand the material, and the examiners did not believe in Lister's method. In a short time, the number of students in lectures dropped from hundreds to a few dozen. When he introduced supervision of the application of the anti-sepsis to his patients in the hospital, the nurses rebelled, claiming that this was their exclusive job.

But against all these difficulties, Lister persisted in his work, and the situation slowly improved.

As a substitute for the unruly students, guests from all over Europe crowded his lecture rooms. With his honesty and pleasant ways he managed to win the respect of the sisters. As for the English doctors and surgeons, he chose to demonstrate to them the correctness of the antisepsis in particularly daring operations. Already in his first year in England, he opened the knee joint to sew up the broken patella of one of his patients. This operation, which is like a death sentence without antisepsis, was successful in his skilled hands, and the patient returned to normal life after a few months. With signs and miracles of this kind, which occurred in front of the eyes of all the old London doctors, he repeatedly confirmed his claim and Pasteur's claim: the microorganisms are the culprits of infections and diseases, and we have the power to destroy them when necessary!

Slowly, the anti-sepsis technique began to enter the operating rooms of England as well. In the past, the surgeon would enter the operating room, put on the overalls stained with blood and pus, sharpen his trusty knife on the heel of his boot and proceed to dismember the person lying in front of him on the table, without saying an unnecessary word. When he was finished, he would move on to the next surgeon using the moving film method, without even changing the knife. The idea of anti-sepsis was the beginning of the end of the hasty and dirty surgeries.

At Lister's encouragement, surgeons stopped using surgical instruments with wooden handles, where bacteria could accumulate, and switched to using metal and plastic instruments, which could be easily disinfected between operations. They would dip their hands in diluted phenol before surgery, and would spray phenol throughout the room to kill the bacteria in the air. It must be admitted that these procedures were also dangerous for surgeons - phenol is a weak acid even in its diluted state. The surgeons who dipped their hands in phenol before each operation would end the workday with their hands red and burning. But at the end of the day, the operated on continued to live and that's what was important to Lister. In 1890, the surgeons' rubber gloves came into use for the first time, thus also solving the problem of the acidity of phenol. After the gloves, gowns and masks were also added to the operating rooms, and the methods were perfected year by year, until they reached the level of sepsis - the almost complete disappearance of contaminants from the operating room. It was Lister's greatest victory.

In 1892, Lister reached retirement age with awards and badges of honor. Universities from all over the world awarded him honorary doctorate degrees, including Oxford and Cambridge and the Queen of England in her honor and herself awarded him the noble title of baron. But all these signs were nothing in his eyes, when his beloved wife Agnes contracted pneumonia in 1893 and died shortly after. That robust man, who did not bat an eyelid in the face of all the ridicule he suffered from the English doctors, lost his wife and his will to live together.

For Lister it was the heaviest blow of all. He aspired to say goodbye to the world, but the world did not want to say goodbye to him. His friends tried to lift his spirits and managed to arrange for him the position of secretary for foreign relations of the Royal Society. Although the grief had left its marks on him, Lister felt again that he still had important tasks ahead of him in the world, and he gave his all to the job. Later he was even elected to the position of president of the Royal Society and president of the British Association.

At the beginning of the 20th century, and although he had long retired from research and practice, Lister was still considered one of the most expert surgeons in England. In 1902, one day before the reign of King Edward VII, the king was diagnosed with appendicitis. The doctors did not dare to remove the inflamed appendix before calling Baron Lister - the highest medical authority in Britain - to give his medical opinion. After the operation, the king confessed to Lister that, "I know that if it weren't for you and your work, I wouldn't be sitting here today."

When Lister turned 80, all of Europe celebrated his birthday. He himself, by nature, did not aspire to this honor, but submitted to his colleagues in all European countries. And yet, on one subject Lister was not ready to compromise: throughout his life Lister emphasized the giants who came before him - Pasteur and especially Zemlweis, whom he learned about only after the invention of anti-sepsis. Lister was part of the international movement in memory of Semmelweis, and with his support the monument in memory of Semmelweis was erected in the city of Budapest. In this, Lister saw the closing of a circle and the payment of humanity's debt to benevolence.

The baron and the man Joseph Lister died in 1912, when he was 85 years old. Throughout his life he won many badges and decorations, but he never boasted about them. For the last honor that they wanted to share with him, he firmly refused. He decided to be buried in Westminster Abbey - the cemetery of the Kings of England - and asked that his body be placed next to the simple grave of his beloved wife Agnes, who preceded him in death by 19 years.

In the next chapter we will tell about Robert Koch, the founder of the science of microbiology in medicine.

[D] : Watson Cheyne, Lister and his achievements, 1925.

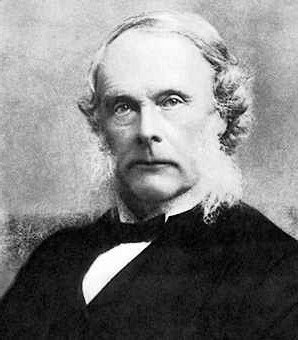

Photo: Joseph Lister.

3 תגובות

Amazing story!

fine! Well done!

exciting!