Think carefully before the next wash: fleece jackets and other synthetic clothes emit microscopic plastic fibers that wash into the sea, harm fish and end up on our plate

Ben Yishai Danieli, Angle - news agency for science and the environment

What's better than a warm fleece jacket on a cold winter day? It warms well, it is soft and lightweight and has two other great advantages: it can be washed - a big plus after a field trip - and it makes us feel that we have preserved the environment, because it is made from recycled plastic bottles.

But it seems that these two advantages - the fact that the fleece is made of plastic and the fact that it can be washed - may together create a significant damage to the environment. A new study, the results of which were recently published, shows that the washing process causes tiny plastic fibers originating from the fleece clothes to be washed into the sea. Along the way they absorb toxins, are eaten by plankton and fish and may climb up the food chain - all the way to our plate.

Hundreds of kilograms of fibers are washed into the sea

The study, the first of its kind in the field of textiles and its effects on the environment, was initiated and financed by the American company "Patagonia", which is known to the backpacker as a major manufacturer of clothing for trips. At first glance, this may seem like a study whose results are known in advance and whose purpose is to paint the company's activities green, but in this case it is actually a company with a long-standing reputation for environmental awareness. The company regularly donates a percentage of its profits to environmental organizations, leads environmental initiatives such as the fight to protect the trout fish and encourages its consumers to repair and recycle the clothes they have purchased, so as not to produce new clothes from new raw material.

What ignited the curiosity of the "Patagonia" people to check the environmental impact of their clothes after washing is probably the results of a groundbreaking study by Mark Brown from 2011. The study examined the tiny plastic waste - plastic particles that are between 3 and 5 millimeters in size and are called microplastics - that accumulated in the sea and on beaches around the world. The results left no room for doubt: a significant part of the plastic consists of tiny polyester fibers (Microfibers), which originate from the water emitted from the domestic washing machines, and which found their way to the sea through the sewers.

From here it was a short road to establishing a multidisciplinary research team to check whether the fleece clothes - the immediate suspects for contamination, since they are made of plastic - are indeed to blame. As part of a collaboration with the University of California at Santa Barbara, "Patagonia" created a diverse team that included experts from various fields, from biology and biotechnology to economics and corporate responsibility.

As part of the study, Patagonia fleece clothes were washed in washing machines. The water emitted by the machines was filtered through a special filter system, then the composition of the substances found in the filtered water was checked. As part of the experiment, new fleece clothes were tested, as well as old clothes that had already been washed many times.

The results of the study confirm the fear: the amount of tiny fibers that are washed from the washing machines ranges from 160 to 2,700 milligrams of fibers per machine, or 1.7 grams of fibers on average. It may sound a little, but when you calculate the order of magnitude emitted by a city of 100,000 inhabitants, it is already 441-170 kilograms (!) every day. The wastewater treatment plants do filter some of the fibers before they release the purified water into the environment, but in the end a huge amount of fibers end up in water bodies - 9 to 110 kilograms of fibers per day, an amount equal to 15 thousand plastic bags that find their way into the environment.

Poisoned fish

The tiny plastic fibers are part of a worldwide problem that has troubled researchers in recent years - and that is the problem of microplastic waste. These tiny plastic particles, which include tiny fibers alongside tiny spheres from cosmetic products and plastic particles that have broken down from larger plastic waste, have been found in seawater samples all over the world, even in the middle of the ocean. Worse - they are found in large numbers in the stomachs of fish and other marine animals.

At this point you are probably asking yourself, "What harm can such small plastic particles do?" The answer lies in the way the marine ecosystem works, along with a pinch of chemistry. Noam van der Haal, a doctoral student in the Department of Marine Civilizations at the University of Haifa, who studies microplastic waste in the marine environment, explains: "As soon as there is a hydrophobic substance in the water - repels water - other hydrophobic substances tend to stick to it, such as toxins that reach the sea from fuel, industry and even from the air. These substances are attached to the plastic, and thus the fish that eats the microplastic is exposed to toxins. At a later stage, when big fish eat the small ones, the toxins accumulate and go up the food chain - and eventually they can also end up on our plate."

The accumulation of toxins in the food we eat is of course a cause for concern, but there is still no agreement on the exact nature of the health danger that lies with us, humans. What is clear is that the first animals in the chain are definitely affected. In a recent study on crabs that ate food contaminated with tiny plastic fibers it was found that they suffered from impaired appetite and growth. Van der Hal is also investigating the effect of microplastic waste on fish, as part of a study under the direction of Dr. Dror Angel. "I'm trying to understand how small fry react to microplastics," he explains. "For example, how long does it stay in the stomach? And do fish have preferences in the microplastic waste they ingest? Are they attracted to certain colors or shapes? These are things that science has not yet been able to decipher."

Nine times more microplastics on Israel's beaches

The field of microplastic research is relatively new, although the problem has been known to researchers since the seventies of the last century. The issue of the tiny plastic fibers, such as those originating from the fleece jackets, is even newer, so the existing knowledge in the field is relatively limited and the challenges are great.

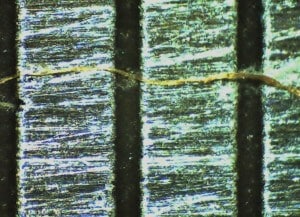

The first and biggest difficulty is to recognize that these are synthetic fibers at all, and not fibers of natural origin. At such microscopic sizes, this is not an easy task at all. "The fibers of cotton clothes and even fibers from oat seeds, for example, are very similar to synthetic fibers," Van der Hal explains. "To differentiate between them, you have to check the molecules that make up the substance, and this is done with a special device called FTIR. But because the diameter of the fibers is so small, the results are inconclusive. And so the situation is that many times there is a misidentification of natural fibers as tiny plastic fibers.

"Another problematic thing is that the fibers are sometimes connected to each other, which affects their count. Do you count a block of fibers as one, or do you separate them and count them separately? Every such decision affects the results of research in the field."

Van der Hal also points to a problem in the experiment conducted by the "Patagonia" company. "It is very difficult to declare such a preliminary study as a study with accurate results. Studies show that tiny plastic fibers are floating in the air everywhere today. If you put cellophane paper in the room, you will see that such fibers accumulate on it. This is something that could contaminate samples of this type, unless they were done in a completely sterile place. In addition, all the fibers found in FTIR had to be checked to make sure that it was not an organic material or cotton."

Due to the complexities described, the current situation of plastic fibers in Israel is not yet clear. "I came across low amounts of tiny plastic fibers in my research," says van der Hal, "but this should be taken with limited responsibility due to the difficulty of collecting and testing the data." However, microplastics of other types are also present: the test conducted by van der Hal showed that along the coasts of the country there is nine times more microplastic waste than elsewhere in the western Mediterranean.

The solution: washing without water?

In light of the new research, is the fleece industry and the fashion industry as a whole facing a historic upheaval? Looks like not yet. "If they stop the production of the fleece, they will cause a break in plastic recycling, so there is a real dilemma here," says van der Hal.

Salvation will not come soon from sewage treatment plants either. "The filters of the purification plants are loaded with so much organic matter, and under such great pressure, that in the end even the tiny fibers pass through them," Van der Hal explains. "If smaller filters are used, the process will become much less efficient and therefore also more expensive. Therefore, the solution should be on the side of the producers."

And on the manufacturers' side, things are starting to move - but slowly. A series of creative solutions currently under development may reduce the amount of fibers that are washed in the wash: starting with washing without water using carbon dioxide spraying at high pressure; Continue with a ball that will trap the plastic fibers inside the machine and prevent them from reaching the sewer; And including coating the plastic fibers with a special material that will prevent them from being released from the garment or installing special filters in the washing machines. But all developments require motivation, and this should come from the industry - and the government.

The American government, for example, made history last year when it passed a law that prohibits the sale and distribution of products that contain tiny plastic pellets. Just like the plastic fibers, the tiny plastic globules found in our face water and other cosmetic products are washed into sewage treatment plants and from there into the environment. In an interview with the "Guardian" newspaper, Mark Brown, the author of the pioneering study on plastic fiber pollution, demands that the government and industry come to their senses and start acting on the issue of tiny plastic fibers as well. "We have already proven that these fibers reach everywhere. Now the government and the industry have to explain what they intend to do about it," he said.

"There are still open questions", Van der Hal concludes. "When we breathe cotton fibers that fly in the air is it less bad than plastic fibers? It could be just as bad. These are things that are very complex and do not yet have an answer, and they need to be answered before deciding to stop producing fleece."

2 תגובות

Clutter in clothing

It's funny that in all these articles they don't point to the root of the problem, the planned obsolescence of products created by the capitalist system to try and create endless demand for products is the one responsible for the huge amount of waste and the draining of resources in the hands of the industry. In East Germany during the communist period, light bulbs were produced that lasted more than 100 years without burning out. Today their expiration is planned by the best engineers. I would expect a scientific site that got to the root of the problem, without that it remains a problem without a solution.