A conversation with Professor Yoel only about the evolution of man, about the side branches in our evolution and why we actually need a time machine. Interviewed by: Dorit Ferns

When you enter the office of Professor Yoel Rak, the first feeling is one of admiration. The walls of his office are covered with wooden cabinets whose shelves display the evolution of the human race in all its stages - the skulls of the clumsy Australopithecus boast a kind of bony carapace to which were once attached powerful muscles that moved its heavy jaws and the skulls of Neanderthal man are impressive in their size and prominent bony ridges.

Yoel Rak, from the Department of Anatomy and Anthropology at the Faculty of Medicine at Tel Aviv University, was born in Germany to a Jewish family from Poland who stayed in the displaced persons camps after the war and immigrated to Israel with his family at the age of two. From his childhood he was attracted to zoology and fossils, and when he grew up he turned to study evolution at the Hebrew University. Since there was no such curriculum, the university allowed Lerk to choose a variety of courses from different fields and put together a unique curriculum for himself. His studies gave him a broad education that served him well in his research, and today, he believes, the universities do not allow such access easily. He completed his master's degree in anatomy, and after nine months in the reserves during the Yom Kippur War, he was accepted, to his delight, at the University of California at Berkeley, to study human evolution and paleontology, where he fell in love with Austrolopithecus robustus - the clumsy one. The reason, he says, is that the clumsy austrolopithecines are essentially a side branch of human evolution, which makes them more interesting. For the story of human evolution is actually "incredibly well documented and incredibly boring" says only.

After straightening up, which was the big transformation, the story can be summed up in three words: the increase in brain volume. The brain grew and at the same time the jaws shrunk, and these two processes are probably related to the fact that processing and cooking food made it possible to maintain an energy-consuming brain, and to increase the large and "expensive" teeth. And what remains, after we have lost the massive jaws of our ancestors, are a chin and a nose - the two characteristics of modern man.

But, as described in this issue at length, the evolutionary tree of the hominids is more like a bush, with side branches that end without continuation. One of these branches is the clumsy Australopithecus, and another branch is Neanderthal man.

A gender that is not a gender

One of the controversies in the field of paleontology today is whether there was indeed an exchange of genetic material between Neanderthal man and modern man. Studies show that our DNA contains genetic material that is also present in the Neanderthal genome. Some researchers believe that this indicates pairings between Neanderthals and modern humans, but only believes that this is not the case. First, he says, there is no evidence of modern human DNA in the Neanderthal genome, meaning that if there was indeed a transfer of genetic information as a result of mating, it was, for some reason, one-way. Second, when you look at the mitochondrial genome, there is no evidence of mixing genetic material, so it is appropriate to call such a reality "leakage" and not gene replacement. Furthermore, the mitochondrial bodies are the energy factory in nucleated cells, and every cell has many such bodies. Mitochondrial bodies are passed to the next generation only through the egg, because the sperm cells are too small, and the part of them, which penetrates the egg, contains the cell nucleus but does not contain mitochondria. For this reason, mitochondrial DNA inheritance is also called maternal inheritance. If there were pairings (on both sides) between Neanderthals and modern humans, we would expect to see a mixing of the mitochondrial DNA as well, evidence of human mitochondrial DNA in the Neanderthals as well.

But far beyond that, Yoel Rak adds: Since the age of modern man is about 200 years (as determined by geneticists) and maybe even less, and the age of Neanderthal man is about 600 years and maybe even more, it is clear that we lack in this gap, of about -400 thousand years, some key players that separate our common ancestor and the Neanderthals, players who were closer to the Neanderthals. In other words they are responsible for the presence of the genetic material in the non-African modern human population. Just convinced that Neanderthals and modern man are two separate human species, if only because their anatomy is so different. Any paleo-ontological standard based on the knowledge of today's zoological reality, the one that paleo-ontologists are equipped with, and on which to judge anything, agrees with this statement.

The evolutionary messenger race

One of the main questions in the field of human evolution today is whether human development is likened to climbing a ladder or is our evolutionary tree more like a bush. The climbing model actually assumes that at each stage, the existing species undergoes changes and becomes the next species (anagenesis model). In this linear model (basically familiar from the common cartoon in which the monkey slowly straightens up and turns into a person), at any given moment there is only one species, which is in the process of transformation. But the scale model is fine and dandy until you find findings in the field that are anatomically inappropriate, such as a skull that has anatomical features that do not match the linear developmental sequence. Such a skull violates an important principle in evolution, and in biology in general, which is the principle of parsimony. According to this principle, if evolution is indeed linear, i.e. one species disappears while the next species emerges, it is illogical, for example, to expect that a certain animal will suddenly have a horn on its forehead, and at the next evolutionary stage it will disappear. It makes more sense to classify the fund owner as a side branch in the evolutionary discourse.

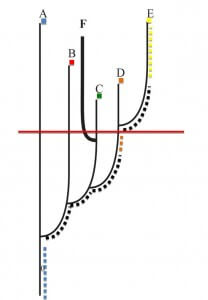

Such side branches can be explained if you look at the evolution of man not as a developmental ladder, but more like a relay race (see illustration). Each species "passes the baton" to the next species, but it itself does not have to disappear. And so several species can live at the same time, as indeed happened quite a bit during evolution, and even produce side branches. The clumsy Australopithecus is one such side branch. Although he did not develop a horn on his forehead, his skull is decorated with a kind of bony tiara to which the jaw muscles were attached. Any attempt to insert such a tiara, which is completely absent from earlier or later species leading to man, on our line of development, violates the principle of parsimony, and therefore it makes more sense to classify the clumsy Australopithecus as a side branch that did not participate at all in the messenger race that led to modern man. Many of the fossils known to us today were like that, including those of our Neanderthal acquaintances.

Grandma, why do you have such a big mouth?

The anatomy of the Neanderthal man is also completely different from our anatomy, and this anatomy supports the Neanderthals being a side branch. One of the interesting differences is the Neanderthal man's oral key. With us, the wisdom teeth are very close to the back of the jaw, but the Neanderthal jaws boast a huge gap in size between these teeth and the back of the jawbone. This, and the different anatomy of the jaw joint of the Neanderthals, which was flatter than ours, indicate that these ancient hominids could open their mouths much wider than us. How much wider? It's hard to tell without the facial and jaw muscles, but in any case their mouth opening was much larger. It is not clear why the Neanderthals needed such a large mouth opening, and this is one of the topics that he is currently investigating with his colleague, William Hylander, an expert in jaw biomechanics from Duke University.

time Machine

And speaking of jaws, when you look at the many skulls that adorn Reck's office, especially the skulls of the bulky, thick-jawed and big-toothed Australopithecus, or of the Neanderthal man, it's hard not to wonder what these ancient people did when they had holes in their teeth. Well, just saying, they didn't have many holes in their teeth. Cavities in the teeth are a side effect of increased consumption of high-starch grains that break down in the mouth into simple sugars that serve as a rich breeding ground for bacteria. Because of this, a high incidence of cavities in the teeth began mainly with the development of agriculture. And even if there are many examples among this exceptional fossil, there is no doubt that the teeth of the hunter-gatherers were much healthier. And what happened when, after all, a hole developed in an ancient tooth? "So they suffered," he says only with a smile.

Just really likes the objects of his research, especially those special side branches, the clumsy Australopithecus and the Neanderthal man. The mysteries they pose make him want to know them personally. "If I had a time machine," says Rek, "on the first trip I would visit the clumsy Australopithecus, and on the second trip the Neanderthal man. And on the third journey," just making a landing, after which he adds: "I would visit my mother." It can be assumed that any Polish mother would be happy to be included in this impressive group.

- A complete skull was discovered in Georgia, which is the earliest evidence of man's inventions outside of Africa

- A stranger in a foreign land

- The skull in Georgia - a head is sometimes just the beginning

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

11 תגובות

I would sell the whole world for mom. This man is weird

Baz Cyr

When I was a child I knew a hero by that name. I don't remember him being interested in mammoths. Especially when it comes to missing links in an article of a short historical time in total "It is clear that we are missing in this gap of about 400 thousand years. "We have been extinct for two thirds of the time of the creation of modern man. According to the explanation in the article, the chance of the evolutionary description tends to 33% less than fifty percent accuracy if I understood correctly.

They didn't look like that

http://www.imj.org.il/exhibitions/2014/face-to-face/

But someone will sculpt themselves for the future and leave a mark on them. Who volunteers?

The article is interesting and exciting

Eyal,

You're used to pieces of beef, much larger pieces of mammoth.

In what nonsense, they cut the mammoth into pieces, he didn't need a big mouth.

Of course the Neanderthals had a big mouth. Today the mother says to the child who is feeding him: Big mouth here is Oiron. So they said to the boy: Big mouth here is a mammoth. We need a big mouth

Skeptic, I have a better evolutionary explanation:

http://ambitiondaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Thinking-Man.jpg

How can we think without a chin?

The human chin (of Spines Spines) is not an inheritance from the ancient humids but is unique to Spines Spines. A possible explanation for the evolution of the human pointed chin (of Spienes Spienes) is an improvement in jaw function, for example moving the position of the teeth forward outside the skull to better utilize the skull space, there may be other explanations why it was necessary to lengthen the chin and strengthen its tip.

I liked the analogy 🙂 I too have always treated evolution as a messenger race, a generation comes and a generation goes... but the genes make it all the way and pass from one generation to the next generation (we are just a vessel, whose job it is to carry the genes).