Computer communication in the sixties did not have a uniform standard at all. A small project that even sought to establish such a standard, sowed the seeds of the Internet as we know it today

In those days the work interface in front of the computer was through punched cards. The technicians worked long hours to prepare the cards and feed them into the computer, then waited a few more hours for the computer to finish its calculations. It was a cumbersome and very inefficient process. Lik understood, mainly based on intuition, that these large machines had untapped potential.

In 1962, Licklider was appointed head of the Office of Information Processing Technologies, within a young research agency of the US Department of Defense called 'DARPA'. He recruited the best brains in the universities and asked them to find a simple way to connect distant computer networks. Since there were no fixed standards for computer networks and each organization chose the computers and technology that suited it, the result was a technological mess and computers that were unable to talk to each other. When Lik's term ended, his idea was still unrealized - but the seeds of the revolution had already been sown.

Paul Baran, a young engineer at the RAND company (a subcontractor of the United States Army) was given a difficult task: to design a communication system that could survive a nuclear bomb. His solution was to build a computer network in the 'fishing network' model: masses of small connections between relatively small computers. Baran's idea had a distinct advantage in terms of price and reliability, since the small computers would be relatively cheap. The bonus in Baran's idea is that if the Soviets want to cut off communications completely, they must destroy all the multitudes of small connections - that is, destroy the entire United States. Actually, maybe it's not such a successful bonus.

In 1969, after several years of preparations and planning, the time had come to turn the theory into reality. Prof. Leonard Kleinrock was one of the world's leading experts on computer switching systems and UCLA, the university where Kleinrock taught, was chosen to be the trailblazer. At UCLA, the first connection point was placed, which was supposed to connect the computer networks of UCLA and Stanford.

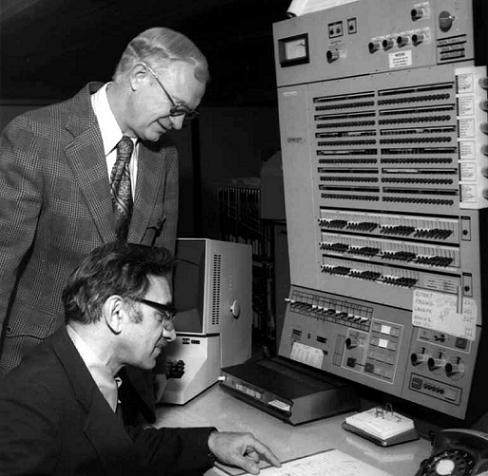

The Kleinrock team worked feverishly to meet the trial schedule. The computer that was supposed to connect the networks was launched only a year earlier. The only time Kleinrock had seen it with his own eyes was at an exhibition, and in this case the massive computer, weighing half a ton, was suspended by hooks from the ceiling and a thug with a large hammer hit it repeatedly to show everyone how reliable and shock-resistant it was. Kleinrock had good reason to think that the exact same computer would be the one to arrive at his lab at UCLA, certainly not a very encouraging thought.

Fortunately for the UCLA people, the computer that arrived worked as expected. Now Kleinrock approaches the task of connecting the two universities. He and another programmer sat in front of a computer terminal with a telephone receiver in hand, and engineers at Stanford sat in front of their terminal and telephone. The goal was to pass the words Log In through the new connection. The Kleinrock programmer pressed the letter L, and the man at Stanford told him on the phone - 'I got an L'. He pressed O, and the man said 'I got O'. He pressed G- and the entire network crashed. This was the beginning of the Internet.

As new networks were added to the Harpanet network, computers had to be added at the connection points in the 'fishermen's network' model. These computers are called 'routers', because they route the information that goes from one computer network to another computer network. More routers means more money, so there was a clear need to lower their price. As anyone who has bought a Chinese-made DVD player has learned firsthand, the words 'cheap' and 'unreliable' are synonymous in Chinese. But the military demanded cheap routers without compromising reliability. What to do?

The researchers who solved this problem in 1973 were Robert Kahn of DARPA and Vinton Cerf of Stanford. Their idea was to give every computer in the world its own unique address, so that the information on the network would be routed just like a letter by regular mail addressed to a specific residential address. This address is referred to as an 'IP address'.

The one who receives the information packets is the router. The router looks at the packet and reads the destination address from it. Nothing else in the information package interests him: whether it is a video clip of Madonna, or a sermon by Rabbi Ovadia - for him it is the same. All the router wants is to move the information packet closer to its destination. The information goes from router to router independently until it reaches its destination, where the destination computer is the one responsible for checking that all the information arrived correctly. Since the routers don't have to delve into the information they are transferring, and since the burden of quality control has shifted to the shoulders of the destination computer, the routers can be simple - and cheap.

In 1989, the Internet began to expand at a dizzying pace. Tens of thousands of computers were already connected to it, and commercial parties also began to keep an eye on the financial possibilities that depend on it. But the general public still couldn't use it because surfing was done using complicated software. The one who changed all this was an Englishman named Tim Berners-Lee.

Berners-Lee was a programmer employed at the CERN research institute in Switzerland. Berners-Lee wanted to fundamentally change the way an Internet surfer sees the information found on another computer in the network. Instead of receiving a long list of different files that are on the computer, the surfer will see a normal page on the screen - like a page in a book or newspaper. The great advantage of such a page is that it can contain the links we are familiar with: with the click of a button, the surfer can reach information found on another computer, without typing addresses or IP numbers. Berners-Lee's links actually connected all the sites on the Internet with connections hidden from view, and allowed surfers to jump from site to site quickly to find the information they needed. Berners-Lee developed the programming language in which these pages are written, HTML (Hypertext Markup Language), and the first browser that was able to display them on the screen.

Tim Berners-Lee was debating what to call the new technology he had developed. The first idea was The Information Mine ('the information mine'), to emphasize the ease with which any surfer can reach any document on the net - but the name was rejected because its initials are TIM, and he didn't want them to think he was some kind of ego-trip. The next name, Mine of Information, was also rejected, because its initials were MOI, 'I' in French. Finally, the name World Wide Web was agreed upon - and the revolution began.

By the way, Douglas Adams once said about the WWW that this is the first time in history that the abbreviation is longer for a phrase than the name it came to abbreviate...

[Ran Levi is a science writer and hosts 'Making History!', a podcast about science, technology and history at www.ranlevi.co.il]

5 תגובות

Jonathan: Whatever happens in the end, you and I (and a few billions more like us) is determined.

I met Robert Kahn. He told me that he was the one who thought of the dots inside the IP address.

The purpose was to distinguish between the ARPANET Internet addresses.

and regarding the transfer of the documents. You should give a link (there are no links in the article) to the value of net neutrality in Wikipedia. Since this is a serious problem on the Internet today, make it neutral.

Net neutrality on Wikipedia

What happened in the end is that you are answering an irrelevant comment here.

Lol

And what happened in the end?