Who has copyrights on the "natural materials" in our bodies and genetic processes and products

Written by Dr. Meir Fogtash

Not long ago I read a fascinating article about Henrietta Lax's great contribution to cancer research, from the early 50s to the present day, and all this without her being aware of it at all.

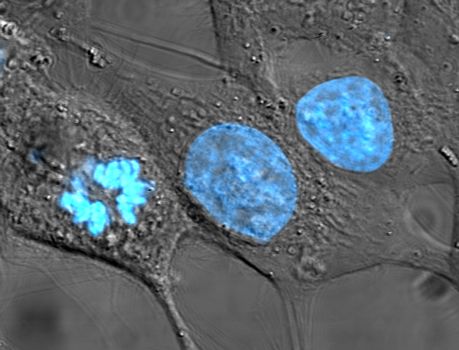

The full story can be read in the article "Who is the woman whose body cells are the world's largest testing ground for cancer research?" (by Shaul Adar, Haaretz, July 2, 2010). I will summarize and say that the cancer cell samples taken from Lax's body (called halo cells) are truly miraculous. The halo cells (and the samples that have been replicated since then) were and are used as the infrastructure on which more than 60 studies in the field of cancer have been carried out, and the hand is still tilted.

The article also states that the poor family of Henrietta Lacks did not benefit even a little bit from the tremendous economic activity that grew alongside the research itself, neither from the income of private entities that were engaged in the production of halo cells and their sale nor from the income from medicinal and medical treatments, which resulted from the research on these cells.

This issue raises one of the main questions in the field of intellectual property: to what extent can we claim ownership or rights in treatments and products, which are based on the "natural substances" in our bodies?

The presentation of the initial draft of the human genome map, in June 2000, and the latest developments in the field of genetic mapping, the use of embryonic stem cells, cloning, genetic engineering, etc., brought the discussion of these issues to new heights. Moral questions, which deal with a person's right to intervene in the act of creation, or in the process of evolution, through genetic manipulation, are gradually giving way to commercial and legal questions, which deal with the ownership of the human "template".

I will stop here and point out that the field of intellectual property deals with the way in which we grant the right of private ownership in products and products based on knowledge, information and intellectual works. Intellectual property rights (such as patent rights, copyrights in literary and artistic works, trademarks of various products and services, etc.) grant the right of private ownership to entities engaged in the development of these products and bringing them to the market.

The issue of private ownership of genetic processes and products is extremely complex. It is worth noting two central motifs.

From the point of view of the private sector, it is necessary to reward companies that invest billions of dollars in the development of innovative processes and products, such as medicines, based on biological processes. In order for pharmaceutical companies to invest such sums, they must have legal protection for the fruit of their efforts, which is mainly based on patent rights.

Conversely, the monopoly resulting from intellectual property rights can allow the owner of the rights to charge a much higher price compared to the situation where these products would have been sold without the protection of intellectual property rights (for example in pharmaceuticals). This creates a difficult problem of social accessibility.

This dilemma was described in 1956 by Joan Robinson of the University of Cambridge as the "intellectual property paradox": to stimulate the development of innovative products in the future, intellectual property rights limit access to existing products in the present.

Another and no less important issue is whether hospitals should be granted the right to reserve intellectual property rights (ie ownership rights) in the results of studies that were based on samples taken from patients treated in these hospitals.

There are also differences of opinion here.

Opponents raise various concerns: biasing treatment and medical research in directions of a more commercial nature at the expense of patient care, creating situations in which doctors and researchers would prefer not to publish the results of their studies for fear of not being able to reserve intellectual property rights in these studies, transferring ownership of knowledge created with public funding to private entities on The account of taxpayers and patients and the like.

In contrast, the supporters (of which I am one) claim that the reality shows that the existing pattern of exploiting intellectual property rights in public and governmental bodies (including hospitals) has actually benefited the public and improved the level of treatment and research. For example, it is currently found that half of the new drugs on the market were developed through collaborations between private industry and public bodies, such as universities and hospitals.

Will the descendants of Henrietta Lacks receive a commercial reward for her contribution to humanity? Most likely not. But the one who probably benefited from the aura cells is the hospital affiliated with Johns Hopkins University in the USA, where the first isolation of the aura cells was carried out.

In the set of considerations, which put the social benefit first, I don't think there is anything wrong with that. It is appropriate that research carried out in public and governmental bodies reach maturity, certainly when it comes to the development of new drugs and treatments. Intellectual property rights are probably a necessary basis for this activity.

Even so, we should not forget the contribution of the only person, the patient, and definitely acknowledge him for it - also in a way that benefits his pocket, him and his family.

Dr. Meir Pogtash is an expert in intellectual property policy and the utilization of knowledge assets. He is a senior lecturer at Haifa University and Ben Gurion University and serves as head of the research division of the pan-European think tank - Stockholm Network.

One response

Patents are a privilege that is granted by virtue of the sovereignty of foreign bodies and the like, in Israel there are no patents on genes at the same level as in the US and people go to Israel to have treatments that in the US cost over thousands of dollars in tiny amounts compared to these..

And in the cultural aspect, intellectual property rights have flooded our culture with trash that is profitable to make for commercial reasons.