The question of the existence of extraterrestrial life has occupied astronomy researchers for decades. The cutting edge of this research is the question of the existence of intelligent life on different planets.

Haim Mazar

introduction

The question of the existence of extraterrestrial life has occupied astronomy researchers for decades. The cutting edge of this research is the question of the existence of intelligent life on different planets. The examination of the subject is currently done in two directions. One direction is the literary direction and it finds its expression in science fiction literature and the other direction is the practical direction expressed within the SETI program.

Finding intelligent life is an intellectual challenge of the greatest importance, the importance of which is difficult to even describe. First, the discovery of intelligent life will categorically prove that we are not alone in the universe. Secondly, an encounter with these extraterrestrials will actually be an encounter with worlds of content completely different from what we have known so far. The best behavior pattern that can describe the encounter with them is the "culture shock" phenomenon. According to the definition, "culture shock" is the set of reactions to an encounter with a foreign culture that is different from what we have known so far. A good illustration of this is the first visit of one of us, without prior preparation, to China or India. It is essentially a meeting between the Western world of thought and the Eastern world of thought.

An encounter with extraterrestrials will have a much greater power. It is an encounter with extraterrestrials who may be biologically different from us, who come from ecologies completely alien to those existing on Earth, who speak unfamiliar languages and whose world of content is virtually invisible to us. Basic tools that will be used for our knowledge will be first and foremost sociology and anthropology. The reason for this lies in the fact that the first thing we will have to do is learn to communicate and understand them. It is basically learning a new language and internalizing basic terms of their behavioral codes. In order to illustrate this, we will do a mental exercise that will look like paintings on the border of picaresque. Suppose there is a planet that is identical to Earth in all its data, except for the density of the atmosphere. The density of its atmosphere is 1.5 times that of the earth's atmosphere (like Titan's atmosphere). A mandatory conclusion is that the heating time of liquids here is higher than on Earth. This is of great importance in the culture of hospitality. The time to heat water to make tea or coffee is very important in terms of what happens in the living room of our home when we host relatives and friends. If the heating time needed for heating is longer, we will certainly notice differences in the behavior style of the people sitting around the table. It may be that the differences are subtle, but by way of extrapolation we can tap from this perhaps a number of other things in this simulation.

From our knowledge of human history it is clear that the technological society we live in did not suddenly emerge from nothing. It was a long and protracted process of hundreds of thousands of years. If we would like to define this development, then it is an evolution of intelligence, and more precisely, an evolution of the cognition of a large public of individuals who work together with the goal of survival at the beginning and in the course of their development also reach intellectual and technological achievements. Any intelligent life form that exists on other stars must pass this route. The same experiments that are done in the framework of SETI basically assume that the same company that exists somewhere is actually a technological company capable of sending transmissions into space. Such a technological level does not appear all at once. There must be what was before, and it is an evolution of cognition at the sociological - anthropological level. This is actually a fundamental condition for the development of intelligent life.

A key question can be asked, what is intelligent life and actually what is intelligence? Getting into this question will require a rather extensive philosophical discussion. For the purpose of our discussion, we will be content with the dictionary definition, which is that intelligence is "the mental abilities to understand things and draw logical conclusions from them" (Eben Shoshan dictionary). In the next step we will raise the question: Is the basic condition the ultimate condition for the development of intelligent life? To answer this question, we will present framework characteristics of several societies throughout human history.

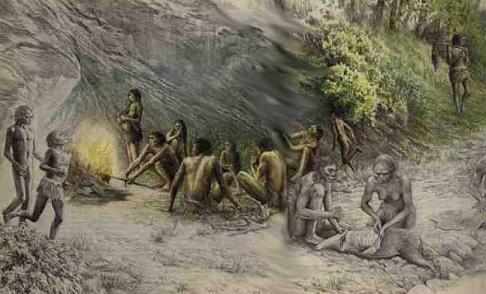

Oral company

An important chapter in the investigation of human history is the recognition of the prehistoric society. Those days when people first began to act in a community framework. Humans began to feel the feeling of togetherness for the first time and as a result they began to externalize their intellectual potential, even if it was essentially July. The distillation and refinement of this potential came later when the writing began to develop. It is difficult to know which languages they spoke and even more difficult to know what the verbal volume of these languages was. A possible way to get even a minimal idea about these languages is to check all the anthropological studies that are currently being done among different tribes around the world and which are illiterate. To illustrate, we quote a passage from the words of the anthropologist Claude Lévi Strauss, which bears witness to a very important linguistic aspect: "The pointed knives of the natives (Gabon's Fang tribe) allowed them to stand with vigorous precision on the type characteristics of all animal species, both on land and in the sea. And to the same extent about the subtlest changes that apply to the phenomena of nature: the winds, the light, the colors of the seasons. in the ripples of the waves and the fluctuations of the crises, in the currents of water and air" (Strauss 1987: 15). From research done among the Hanuno tribe in the Philippines, it becomes clear that "all the Hanuno's activities, or almost all of them, require a close acquaintance with the local vegetation and an accurate distinction between the varieties of plants. Contrary to the opinion that the societies that live in scarcity only use a tiny part of the local vegetation, this society makes use of 95% of the varieties of vegetation in its environment... The Hanuno people sort the winged animals in their environment into 75 categories. They distinguish 12 species of snakes... 60 types of fish... more than a dozen "forms" of sea and freshwater shells as well as spiders and centipedes... the insects in their thousands of forms are divided into 108 categories, each of which is given a name. And of those, 13 refer to ants and termites... They can point to more than 60 groups of molluscs in seas and more than 25 groups of molluscs on land and in fresh water... 4 types of leeches... In total, the researchers recorded 461 types of animals that the natives know how to identify" (Strauss 1987: 16 ). Members of these tribes take a rational step that allows them to organize their common life. They invent words for the various natural phenomena they see. The same words agreed upon by all are used by them for communication among themselves. They name plants, they name animals and they name natural phenomena.

Since they have given these names they sort these names into different categories. That is, they group groups of names with similar characteristics and give these groups their own names, thus creating new words. Members of these tribes also turn out to have abstract thinking. They still do not articulate their thought processes verbally, but they are aware of the need for words to connect other words - these are the comprehensive words in this categorization. They actually create a linguistic hierarchy, what is of low rank and what is of high rank.

This ability to abstract was reflected in various aspects of life, which were essential to the lives of the community members. The most prominent of these fields is the narrative field and the reference is to mythology. For this purpose we will give an example from Polynesian mythology: "Fire and water united and from this pairing the earth, the rocks, the trees and everything else were born. The squid struggled with the fire and was beaten. The fire fought with the rocks that won, the big stones fought the small ones. The latter were victorious. The small stones fought with the grass, and the grass won. The grass wrestled with the trees, it was beaten and the trees won, the trees wrestled with the liana plants, they were beaten and the liana plants were victorious. The liana plants have rotted. The worms multiplied within them and worms became human beings" (Strauss 1987: 243).

The story describes the development of man. A preliminary linguistic examination will show that this is a text with a large volume of words, which includes nouns, verbs, names, bodies (grammatical), linking words and the use of the time dimension to describe a sequence of events. Since these societies did not know the script, these stories were passed down from father to son for generations. The language is therefore used by the members of the community not only for communication among themselves, but also in terms of collective memory to preserve the community framework. What came before why, the invention of new words for the purpose of developing the collective memory, or the collective memory for the invention of new words is difficult to know, but it can be assumed with high probability that these two variables are interdependent and for this reason they probably appeared at the same time.

The development of writing and collective memory

Collective memory takes a dramatic turn with the invention of writing. The script allows the company that uses it to consciously preserve its history and pass it on in an orderly manner to future generations. The oldest society known to us that had writing is the Sumerian society that appeared in the Mesopotamia area around 3500 BC (Kramer 1982: 15). This ability to preserve the collective memory makes it possible to write down a wide variety of topics that have a fundamental impact on the very existence of the Shomirs as an orderly society and are governance orders, behavioral codes in the form of laws, education, decision-making, technological knowledge and medicine, theology, myths, epics and literature. Indeed, the archaeological findings reveal an unusual abundance of written material. It is difficult to accurately assess which area of this set of issues is more important. The cumulative experience of the anthropological research and the sociological experience show that at the macro level these fields flow into one another into a single treatise that defines the essence of a given society. In any case, it is appropriate to refer to several aspects of exceptional importance. Kramer points out that among the findings in the Louvre museum there is a small tablet whose owner "divided each side of the tablet into two columns and using tiny script managed to write on this small tablet the names of sixty-two literary compositions" (Kramer 1982: 283). The Sumerian society realized that it is not enough to write down the entirety of their activities, but this information must be sorted in an orderly manner, so that others can also use it. There is a classification of the literary information here, and this is already an intellectual step up in terms of the cognitive operating patterns of this society. This leap is also expressed in the budding of historical writing. This is not historical writing as is customary today, but in the examination of mentions of events from an earlier passage of the Shomirs. Kramer points out that "one of the certificates stands out among the others, in its abundance of details and the clarity of its meaning. It is the work of one of the archivists of Entemen, the fifth ruler in the line of governors of Lagash after Oranense. The main purpose of the writer was to note the restoration of the border canal between Lagash and Umm. After that it was destroyed in the fight between the two cities. To put the event in the proper historical perspective, this archivist saw the need to describe the political background. He does mention, in short, in a nutshell, some of the important details about the struggle for power between Lagash and Umm, the kind of times from which written documents have been preserved - that is, from the days of Meshilam, ruler of Sumer and Akkad in approximately 2000 BCE" (Kramer 1982: 92). The historical treatment is specific and is mentioned due to its relevance to the subject of the writer's treatment.

As for philosophical worldviews from the written material found in archaeological excavations, it appears that the keepers did indeed have their own philosophy, but it does not grow out of questioning and investigation, but in a descriptive - narrative way in which what is happening in their world is described. The conservative philosophers, if one may use that term, were essentially storytellers. "In order to explain the course and operation of the world, the Sumerian philosophers needed not only gods of various kinds, but also impersonal forces, laws and divine judgments. The laws of the gods, in their opinion, determined the course of the world from the beginning... In a special way it was determined that the "m" (laws of the gods) determine the path of man and his culture" (Kramer 1982: 155).

Research company

In contrast to the Sumerian society, the Greek society is an inquisitive society. This is a company that excludes people who ask questions. "They don't have the idea that there are things that are outside the fields of occupation and interest. One of the sacred principles of most of the Greeks... is that there is no end to investigation and thought, there are no restrictions on the scope of the investigation and there is no subject that should not be investigated" (Glicker 1982: 15). Greek society is a curious society and out of an infinite desire not only to know, but also to understand, they break through psychological barriers that ancient societies as well as their contemporaries imposed on themselves, and investigate every subject that comes to their mind. The investigation is actually a more basic need, such as the various biological needs. The fulfillment of this need comes in the form of thought, investigation, debate and discussion. This thing is part of human nature, in their view, perhaps the most important part of nature. It is no coincidence that Aristotle begins his metaphysics with the words: "All human beings by nature long to know" (Glicker 1982: 15-16). The world of Greek content develops a new thing, which according to the sources known today was not there before, and that is self-awareness. The beginning of the Greek thought begins in the 6th century BC in the person of the thinkers Thales, Anaximder, Anaximenos. All three were active in the city of Miletus and it continued for hundreds of years later and reached one of its greatest peaks in the writings of Plato and Aristotle. We therefore have a society that puts forward a philosophical enterprise of enormous dimensions, which preserves this enterprise in the scriptures. Although some of the writings of these thinkers have been lost over the years, the part that has been preserved can testify to the power of Greek philosophy and from these writings it becomes clear that this philosophy examined and researched both natural and social phenomena in their various fields. We find here astronomical research, mathematical research and historical investigation, in contrast to other cultures in Mesopotamia for example. Greek society grew historians who gave a very detailed report, about their period and periods before them.

An obvious question is why other societies have not reached such extraordinary intellectual achievements. Among the set of possible reasons, we will mention here two central ones, which are the linguistic reason and the psychological reason. From the reading of Homer's works "The Iliad" and "The Odyssey" it appears that in ancient times the Greek language reached such great lexical richness, to the point that the users of it were able to describe various subtleties, in describing their surroundings, in describing their feelings and with a high definitional diagnostic ability. This ability is an even more essential basis for philosophical inquiry. A striking example of this is Aristotle's book "The Poetics" (Aristotle 1972). In this book, Aristotle examines the entirety of Greek poetry 500 years back in time. This is the first book, as far as is known in world literature, that deals with the problems of poetry from a scientific point of view, and to write a study of this kind, it is necessary to define the different types of literature. In fact, it is impossible to carry out any research without the researcher having a rich linguistic ability to describe the phenomena being studied. This rule is important both in literary studies and in studies of various natural phenomena. Philosophical inquiry realizes the linguistic ability only when it passes a certain threshold and this is the cognitive threshold. The cognitive threshold is that point in time in the history of a given society, in which people in this community begin to ask questions about their world and the world of phenomena operating in their environment, put their opinion in writing and the other future generations argue with this opinion, and with their own contemporaries and develop their own philosophical changes in these matters and other matters that can be derived from them.

The empirical investigation

The investigation that the Greeks excelled in lacks the practical dimension. It was not an empirical study. There were indeed attempts to go in this direction, but these were marginal in nature. They were somewhere on the periphery of the Greek scientific community and also very late in the Greek scientific enterprise. The most prominent example of this was Haron who worked in Alexandria in the 1st century AD (Mazar 1995: 27). The first empirical studies were carried out for the first time in a systematic way in the 17th century by Galileo Galilei, whether it was experiments in mechanics or astronomy. The empirical dimension began to grow slowly until it included the entire academic community and it was reflected in the systematic preparation of experiments, the design and manufacture of research instruments and the publication of the results of the experiments in an orderly manner in the scriptures. Science has given the public an organizational and institutional structure that is largely funded by the state.

Two historical phases of the research must be distinguished here. The first stage is the individual research, which is done by a single researcher who privately budgets his experiments and the second stage is the budgeting that is done within the appropriate frameworks of the universities and private research initiatives. This phase began to develop in the 19th century. That's when scientific journals as they are known today also began to appear. The scientific studies are beginning to have a pragmatic character. Knowledge does not remain on the shelves of researchers, but finds use in everyday life. The result is that today we talk about science and technology.

In retrospect, it can be said that society as a whole went through two more cognitive phases. One threshold where the scientific community is no longer satisfied with theoretical studies and opens the next path to back up (either for confirmation or refutation) the theory with experiments and the second threshold is the organization and industrialization of research. The research is a product of society, when a trend develops to derive practical benefit from it.

The inability of the Greeks to pass the first cognitive threshold can be explained by various reasons.

1. Arthur C. Clark in his article "Technology and the Limits of Knowledge" (1983:237) claims that the failure of the Greeks resulted from their inability to combine knowledge and technology and that this is one of the great tragedies of humanity. Despite their extraordinary intellectual skills they failed in empirical science. The Greeks laid the foundations for science and the entire Western culture but failed to implement it. Part of this failure can be explained by their discouragement from applying science to everyday life. They even despise each other for that.

2. Samborsky Shmuel claims that their insights are "the fruit of a genius spark of thinkers who gave a distinct and clear expression to a scientific idea in a so-called empty space without any professional backing and in the absence of any resonance in their environment. Because they preceded the historical development, their words remained in the examination of voices calling in the desert" (Samborsky 1982: 241).

3. The economy of Greece was basically a slave economy. The Greeks did not see fit to develop work tools that could replace the slaves. Slaves were a cheap labor tool that was abundant and unlimited.

Conclusions

The presentation of framework characteristics of different societies on the timeline starting from the pre-historic period to the present shows an evolutionary process in the development of intelligent life and it includes the following stages:

1. The development of communal life while developing a collective identity.

2. At the same time, linguistic development took place among those living in those social settings. This linguistic development is essential and actually required by this way of life, to enable effective communication between the members in these frameworks, for the performance of shared tasks.

3. A parallel development of the collective memory by increasing the verbal volume of the language, while creating an internal level within the language of the vocabulary, the sorting of the world of phenomena and the development of mythological fiction passed from father to son.

4. Improving the collective memory by inventing writing and a detailed record of the existing treasure of knowledge.

5. Breaking a cognitive barrier that is reflected in the willingness of a given society to explore the world of phenomena operating around it and itself, where this willingness is conditioned by the existence of a verbal volume large enough for this purpose and by the continuous development of the language.

6. The breaking of another cognitive barrier that finds its expression in the development of various technologies.

As can be seen from these words, intelligence already existed in the early stages of communal life and is related to the ability to communicate between people working in a communal framework, even if their vocabulary is basic. An intelligence that has a low technological component like the Greek society or a technology-rich one like today's society already requires evolutionary processes in intelligence. Hence, if as part of the SETI project intelligent life is being sought in the universe, the same technological companies that are seeking it in the universe, during the evolution of their intelligence, what determines whether this technology will be lower than that existing on Earth, equal to it, or more advanced than it depends on the pace of evolutionary processes These, whether they are slow or fast.

Other important elements that determine the rate of technological development are the willingness to internalize innovative knowledge and the parallel between theoretical knowledge and practical knowledge. An example of the willingness to internalize knowledge can be used by Greece. If the Greeks in the 1st century AD had adopted Heron's steam engine, we would probably be deep in space today (Mazar 1995: 27). Another and much later opportunity was in the days of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). If in his day there was a technology that enabled the implementation of all his plans, then the technological progress would have been accelerated by several orders of magnitude and the technological achievements of our time would have appeared earlier.

Summary

What is required from this discussion, even if it is succinct, is that the evolution of intelligent life is actually the evolution of cognition at the macro level, when those with high-tech cognition do not and cannot reject the wisdom of life of those with low-tech cognition. The political wisdom of the kings of Babylon, for example, was not inferior to the political wisdom of statesmen nowadays.

Sources

Aristotle - on the art of poetry, published by Notebooks for Literature, 1972

Glicker Yohanan - the rise of Greek philosophy. Broadcast University, published by the Ministry of Defense, 1982

Mazar Haim - Did Haron precede Newton All Kochavi Or Vol. 23 Issue No. 1 Spring 1995

Even-Shoshan dictionary

Strauss Claude Levi - The Wild Thinking Poalim Library 1987

Shmuel Samborsky - "Early and Late in Scientific Thought" Science 5th 1982