How could diseases cause modern humans and Neanderthals to exist side by side for years in Israel - one of the few places in the world where such coexistence was created? And did they contribute to the extinction of the Neanderthals in the end?

A central question in Neanderthal research is why they disappeared from Eurasia about 40 years ago, after having existed there for hundreds of thousands of years, and were replaced by modern humans in a relatively fast process that lasted only a few thousand years. Did we, an African hominid, have some advantage over our European and Asian cousins that led to their rapid extinction? Many hypotheses have been written about this question and researchers continue to discuss different explanations. An even more intriguing question arises from the archaeological findings, mainly from Israel. These suggest that the two groups existed side by side in the Levant (the area of present-day Israel and its neighbors) for many years. They met in our area at least 130 thousand years ago, but tens of thousands of years passed from the time of the meeting until the process of the Neanderthals' disappearance and the spread of modern man throughout Eurasia began. why? What stabilized the front of contact between the species for so long, and why didn't our ancestors spread north much earlier? Perhaps the answer to this question also holds the key to understanding the extinction of the Neanderthals.

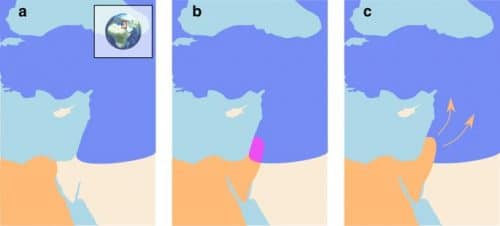

A new study offers a new explanation: diseases. Evolution researchers, ecologists and archaeologists from Stanford, Berkeley and the Hebrew University took part in the study, published in the journal Nature Communications. According to this explanation, each of the groups - modern man in Africa and Neanderthals in Eurasia - faced a different set of infectious diseases and its members developed resistance to different bacteria and viruses during hundreds of thousands of years of separate evolution. When the populations met in the Levant, diseases began to pass between them. The encounter produced such a burden of disease that modern humans were prevented from spreading outside the Levant, areas where Neanderthal diseases were common, and Neanderthals for their part could not spread south for a similar reason. In this way, the diseases stabilized the front of contact between the two groups, creating a narrow area of coexistence in a limited geographical area. Over time, the populations began to mix gradually in the area of the contact front. As a result, genes that confer disease resistance began to move from one group to another. In this way, the groups could acquire resistance to the new diseases that threatened them, and gradually the burden of diseases created by the meeting between them decreased. Finally, after they had acquired sufficient resistance, the disease burden barrier that had limited the spread of populations to new geographic areas was removed until that moment.

To understand the phenomenon in depth, the researchers, led by Dr. Gili Greenbaum from Stanford University and Dr. Oren Kolodani from the Hebrew University, developed mathematical models to describe the dynamics of the spread of diseases and the transfer of genes between populations. The models showed that the meeting between the two groups was expected to create a prolonged period of time in which the burden of diseases is high, the populations near the front of contact are limited, and each group tends to isolate itself to minimize the rate of transmission of new diseases to its members. At this stage, the models predict a stable disease burden and accordingly, overlap between the populations was expected to be limited to a limited geographic area. In addition, the models predict that finally, suddenly and relatively quickly, the burden of disease will decrease and the readiness for contact between the groups will increase, which could have undermined the front of contact and allowed spread beyond the Levant.

These models explain how diseases could dictate a long period of time from the initial meeting between the populations to the beginning of the spread of modern man outside the Levant. However, the question remains: Why was it precisely us, modern humans, who spread at the expense of the Neanderthals, and not the other way around? To answer this question, the researchers examined models in which the burden of diseases at the time of the meeting between the populations is not the same. Modern humans have been dealing with tropical pathogens in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years, while Neanderthals were dealing with pathogens of temperate climates in Eurasia. Because of this, there is expected to be a difference in the nature of the set of diseases that each of the groups carried. Other studies show that today, the tropical disease burden is greater than the disease burden of temperate climates, and it is likely that this situation also characterized human populations in the past.

The researchers' models that took into account the different nature of the set of diseases in the two groups indicated that the group that brings more diseases with it overcomes diseases of the other sex faster, and that over time the gap between the groups in the burden of diseases is expected to grow. The models suggest the possibility that, finally, modern man was almost entirely freed from the burden of Neanderthal disease, while Neanderthals remained vulnerable to the diseases of modern humans. Now equipped with both resistance to Neanderthal diseases and an arsenal of diseases to which Neanderthals were susceptible, modern humans were able to spread into Eurasia while spreading diseases to Neanderthals, diseases that contributed to their extinction. The research shows that disease dynamics, combined with evolutionary processes of gene exchange, can explain both the long period of time in which two species existed side by side with limited overlap and the sudden change, in which modern man spread beyond the Levant and resulted in the disappearance of the Neanderthals.

The results of the research actually describe similar processes, some of which even occurred in recorded history, in which human groups were separated from each other over time, evolved with various diseases, and met again after thousands of years. For example, during the last thousand years, every time the white man arrived from Europe to new continents and islands - America, Australia, New Zealand, or the Canary Islands - the local residents experienced a heavy burden of disease, which reduced the populations and contributed significantly to the white man's takeover. In these cases, the inequality in the burden of disease was in favor of the Europeans. It is possible that similar processes also occur in other animals, and not only in humans. For example, when squirrels of North American origin arrived in England several years ago, they began to spread a deadly disease, and the local populations began to decline. The new study offers a new way to explore how disease can shape interactions between species, and it suggests that disease played a more significant role than we thought, and may even be the main reason why we, modern humans, became the only human group on Earth.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- What caused the extinction of the Neanderthals?

- The Neanderthals lived in stable settlement systems for a long time before disappearing from our region

- Why was the thorax of the Neanderthal man different in structure from the modern man?

- DNA tests made it possible to discover a mixture of Neanderthals and Denisovans

2 תגובות

Joash:

Because it's an island with a limited population size, so the white invader won.

The white man brought diseases from the outside world to the island and infected the islanders. The whites infected themselves and may have died, but there are always new whites from outside, the locals, on the other hand, died out except for a small % that developed resistance

A beautiful theory that is denied immediately afterwards with examples, which does not bother the writers.

Research premise

—–

Burden of tropical diseases in the modern man compared to the paucity of diseases in Nadertal

example

—

The European explorers who arrived in the tropical islands caused the locals a great burden of disease.