In biological control, the forces of nature are harnessed to fight agricultural pests. In recent years, the field has received renewed attention, with the tightening of restrictions on the use of chemical pesticides. In Kibbutz Sde Eliyahu, they have turned biological pest control into a leading industry, and breed insects that are good for pest control - also for export

Itay Nevo, Galileo

In 1886, the citrus industry in California was on the verge of collapse. Many orchardists uprooted their trees, or burned the orchards, the amount of the harvest reached an unprecedented low, and the value of the orchards' land plummeted. The cause of the catastrophe was the citrus weevil (Icerya purchasi) - a tiny aphid that sucks the sap from the leaves.

The aphid mainly damages young trees, but in large numbers the aphids may soon kill an entire tree, just as happened in California. Most of the pesticides we know did not yet exist at the end of the 19th century, and attempts to spray with substances that were used then, such as cyanide, hurt the farmers more than they affected the aphids. The plague quickly spread through the orchards, and the helpless growers destroyed entire plots in an attempt to prevent the aphids from spreading further.

The US Department of Agriculture was called to try to help the desperate gardeners in California. The chief entomologist at the office, Charles Reily, decided that the solution to the plight would come from overseas: since the aphid had been discovered in California less than 20 years earlier, and since it was not recognized as a pest in many parts of the world, Reily assumed that the aphid's country of origin had natural enemies. which prevent it from multiplying at a dizzying rate and greatly reduce the damage it causes to farmers.

Riley sent letters about it to all corners of the world, and indeed received a reply that in Australia a parasitic fly attacks the aphid and curbs its population size. Reilly asked to immediately send an entomologist to Australia, to examine the fly, and bring details from it to California, but just like nowadays, the politicians entered the picture. Congress did not approve the request, and even stated in its decision that the budgets of the US Department of Agriculture are not intended for trips abroad.

In the end, after heavy pressure and many political twists and turns, the US State Department agreed to budget $2,000 for an entomologist's trip to Australia. The entomologist Albert Koebele was chosen for the task, who indeed found aphids infected with the parasitic fly in Australia. He collected several thousand individuals for shipment, and with them he also sent Vedalia beetles (Vedalia cardinalis) - a species of ladybird, which he noticed that its adults feed on the ladybird.

The insects sent by Kovala were placed under a tree infested with aphids, and within two weeks it became clear that the beetles greedily devoured the aphids and cleaned the infested tree almost completely. They multiplied rapidly, and were distributed among farmers throughout California. Within six months, they cleaned the California orchards of the deadly aphid, and the citrus industry flourished again. The 129 beetles that survived the journey from Australia in Kubla's shipments, entered the pages of history as the first recorded success of biological pest control.

biological warfare

This success was preceded by many other successes, apparently, but their scientific documentation - if any - has been lost. It is known, for example, that already in ancient China they used to cultivate ants that preyed on pests in the orchards, and they would even place bamboo canes as a bridge between the trees, to help them. A similar method was discovered in the 18th century among date growers in Yemen, and seems to have prevailed there for hundreds of years. Around the same time, birds were brought to Mauritius from India, to prey on the red locust that made a name for itself in the agricultural crops on the island.

Biological control, sometimes also known as "biological warfare" or "biological pest control", is based on the simple principle that, as usual, every organism in nature has another organism, and usually much more than one, that causes it fatal damage. Of course, this principle also applies to those who we define as "pests", because they damage agricultural crops, or farm animals, transmit diseases to humans, or simply cause infiltration among peaceful and peace-loving people, even without causing real damage (such as cockroaches, for example). When we manage to harness those natural enemies that exist in nature to control the pests as we are interested in, this is biological control, as opposed to chemical control, which is based on the use of toxic substances that kill the pests.

The natural enemies are usually divided into three main groups: predators, parasites and pathogens. The idea of predators is actually demonstrated in the story of the Vodalia beetles. "Moshe Rabbanu's cows" of their kind (also known today as "moshes") prey on the aphids that are harmful to crops, saving them from damage. But the method is not limited only to insects, nor only to agricultural habitats. Placing nesting houses for birds of prey in the fields, to encourage them to live in the fields and prey on harmful rodents, is biological control using predators, as is the release of fingerlings that feed on mosquito larvae in pools of water, and even tying up a donkey in the yard so that it eats the weeds that we define as bad.

A parasite, according to the "Aven Shushan" dictionary, is: "an animal or plant that resides on the body or inside the body of another animal or plant, and feeds on it." Many of the parasites we know are themselves harmful, such as ticks or lice; Most of them do not kill the host - the animal or the plant from which they feed (otherwise they would cut off the staff to feed them).

But in the world of insects there is a whole group of deadly parasites, called "parasitoids". In these species - the majority of tiny wasps, and a minority of flies - the females lay their eggs inside the bodies of other insects. The larvae hatch inside the body of the unlucky host, and begin to eat it from the inside. Within a few days the host dies, as a new generation of the deadly parasites finishes maturing inside his body. Such parasitic flies were found by Kubla, the entomologist who was looking for natural enemies of the citrus fruit, and they also participated in the extermination of the aphid. But the beetles were more effective in this case, mainly because the aphid population was huge in size.

Slow restraint

Those who think about the practical side of pest control, immediately understand that while an aphid attack takes a few seconds, its control by parasites lasts several days, and therefore the control of pests with this method is much slower. However, in most cases the pest does not break out in such large numbers, and the farmers start the pest control long before there is a need to set fire to the crops. In such situations the superiority of the parasites is revealed: the female wasps and flies are much more efficient than the average predator in locating the victims. Therefore, by means of parasites it is possible to curb the population of pests, and to reduce it more than by means of predators, which are mainly effective against very large populations of pests.

In humans and other mammals, diseases are mainly caused by bacteria, viruses and fungi, called pathogens. The same goes for insects. Many microorganisms cause fatal diseases of arthropods, and one of the challenges of biological control is to harness such pathogens for use against pests. The most famous example is the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, or Bt for short, whose toxin kills mosquito larvae. Fungal spores and other microorganisms are also used against harmful insects.

The success of the operation to exterminate the citrus plant in California resulted in other such operations around the world: the cultivation of sugar cane in Hawaii, which was one of the pillars of the islands' economy, was saved at the beginning of the 20th century after entomologists brought from Australia and Fiji bedbugs that fed on the eggs of the sugarcane cicada (Perkinsiella saccharicida), which made names in plants. A few years later, the growers were once again helpless, this time in front of a leaf beetle (Rhabdoscelus obscurus), whose hungry larvae threatened to destroy their source of livelihood. This time it was parasitic flies, brought from threats in the Pacific Ocean, that managed to curb the pest and save the sugar canes and the farmers.

In Australia, it was actually a weevil, and not a harmful insect, that wreaked havoc on the continent's economy. Cacti, which immigrants brought with them as ornamental plants in the 19th century, spread quickly, and in the absence of natural enemies, within a few years they covered millions of dunams of agricultural and pasture lands. So great was the takeover of the cacti that residents in Queensland had to abandon their homes. Their mechanical displacement was not effective enough, and chemical control was too expensive due to the enormous size of the area they covered.

The solution was only found in 1925, in the form of the cactoblastis moth (Cactoblastis cactorum) which was sent from Argentina - and was of course only one of dozens of insect species that were hunted without success in the dreaded piles. The larvae of the Cactoblastis proved to have an inexhaustible appetite, devoured acre after acre, and within a few years freed the areas occupied by the cacti for Australian farmers.

Biological control: fight pests through nature

Dozens of successful pest control operations were completed in the first half of the 20th century. Many crops, from the coconut trees in Fiji, through the orchards in Florida and Cuba, the persimmon trees and tea in Japan, to the coffee trees in Kenya, were saved thanks to the importation of natural enemies from the countries of origin of the crops and/or the pests. However, over the years, biological control has receded from the face of the new star that rose in the sky of agriculture - chemical control.

At the time when Riley and Kubela saved the California orchards, the pesticides available to farmers were extremely limited. Substances such as compounds of cyanide and arsenic, not only are they expensive, but their effectiveness in exterminating pests is relatively low (some of the substances are also highly residual, meaning they decompose very slowly in nature). On the other hand, the substances were actually very effective in harming the farmers themselves, and quite a few breeders paid with their health and even their lives for the exposure to the deadly compounds. With the development of the chemical industry, more viscous substances were made available to farmers.

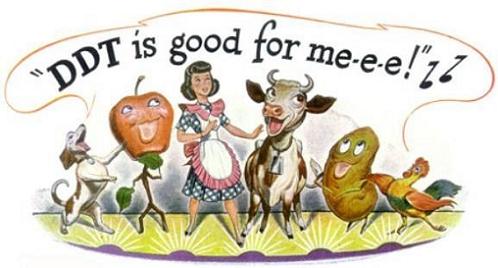

That is, substances that mainly harm insects, and less so other animals and plants. Such materials were more effective and above all - safer. Their mass production and the progress of chemistry greatly reduced the prices of pesticides. The development of aviation at the same time led to the birth of spraying from the air, which made it possible to make even better use of the properties of the new materials. The peak of the era of chemical pesticides was recorded in 1939, when scientists announced a new substance: Dichloro Diphenyl Trichloroethane, or DDT for short.

The magic formula that failed

DDT was synthesized in laboratories more than 60 years earlier, but it was not until 1939 that an organic chemist from Switzerland, Paul Muller, insisted on its great effectiveness in killing insects. The substance acts on the nervous system of the insect - it inhibits the closing of ion channels in the nerve cells, and causes an uncontrolled release of nerve impulses, which leads to the quick death of the insect. Unlike biological control, where it takes days and weeks to see results, DDT provided farmers with the ultimate solution - one spray, and the pests are left dead. Furthermore, the natural enemies never achieve complete extermination of the pest, while the new miracle provided exactly that: after spraying, not a single insect remained in the field - harmful or beneficial, to the great joy of the "cleanliness" lovers.

Not only the farmers were loyal consumers of DDT, but also the health authorities. These are the days of the World War, and the fear of epidemics gives rise to mass spraying operations, such as in Naples - where a typhus epidemic raged when American troops arrived in the city. Typhoid fever is transmitted by lice, and widespread spraying of the city and its residents with DDT destroyed the insects and cured the epidemic. The substance, by the way, was considered so safe to use that the sales agents used to sip it to demonstrate it to farmers.

Only a few years later, farmers were amazed to find that DDT no longer affected pests. The use of huge quantities of the substance resulted in the rapid selection of insect populations that developed resistance to it, and taught the chemists a painful lesson in evolution (see box). Green organizations and health organizations also started raising an outcry, when it became clear that the substance was not as safe as they thought. It almost does not break down in nature - and this is how it accumulates in the food chain: from dead and alive insects and from sprayed plants it reaches the stomachs of large mammals, as well as those of their predators.

It turned out that the exposure of birds to the substance damages the integrity of the eggs laid by the females - the amount of calcium in them is low, and the result is very fragile eggs, only a few of which survive until hatching. The DDT is washed from the fields into the rivers, and reaches fish and even marine mammals. After several decades, the ecologists discovered DDT everywhere - fruits, vegetables, meat, fish and even in breast milk, and also discovered that in high concentrations it is a carcinogenic substance. In the 70s and 80s of the last century, the use of the substance was banned in most Western countries.

The disillusionment with the euphoria of DDT marked a turning point in the history of pest control in agriculture. The scientists and breeders realized that there are no miracle cures, and even though the search for new substances continues all the time, their use is more problematic - insects develop resistance very quickly, and other pests, such as mites (which belong to the arachnids) - even more quickly; The material should be safe to use, not only for humans, but also for other animals, and even for certain insects, so as not to harm beneficial insects, such as bees for example. All of these have opened the door to the return of biological control in recent years.

Import, conservation, reinforcement

Three main strategies are used in biological control: importation, conservation and reinforcement. Importing natural enemies is the classic method, as was done with citrus production in California. Every organism has a natural enemy where it exists for a considerable time. Agricultural problems erupt when a plant or pest is moved to a new location, where the pest has no natural enemies. This may also happen if a harmless insect arrives in a new country and discovers a tasty and unfamiliar growth. If it has no natural enemies in the area, it could easily go through a population explosion, causing severe economic damage.

In all these cases, the method is to return to the country of origin - of the growth or of the pest - finding the natural enemies, and establishing them in the new place. However, finding the appropriate natural enemy sometimes requires many years of research, and many times, even after it is found, it does not establish itself in the new area, due to differences in the climate, the composition of the vegetation or the other species in the area, and sometimes even due to human activity, such as spraying against pests, which also harms it .

In the conservation method, an attempt is made to help natural enemies that already exist in the habitat to establish themselves and become more effective against the pest. For example, plants are planted near the field (or in it), which the natural enemy can feed on when the level of the pest it attacks is too low, the spraying regime against pests is changed so that it does not harm the natural enemy, and various actions are taken to encourage it.

The third method is the reinforcement method. Here, a large amount of the natural enemy is sprinkled in the field, just like a pesticide. The scattering is done according to the type of pests and their population level, and it can be repeated if necessary. This method is the only one that has developed into an economic branch: here a very large amount of the natural enemy (from commercial cultivation) is required, and the need for repeated dispersions, at least once a year, creates an economic basis for the breeders of the natural enemies.