In a huge refrigerator at Ben Gurion University, in a deep freeze of 70 degrees below zero, one of the largest DNA databases in Israel is found. As part of an extensive project to identify the genes associated with hereditary diseases and to treat them, about 2,000 samples were collected from Bedouin families. Opponents of the program say it is actually perpetuating

Tamara Traubman, Haaretz 05/05/03

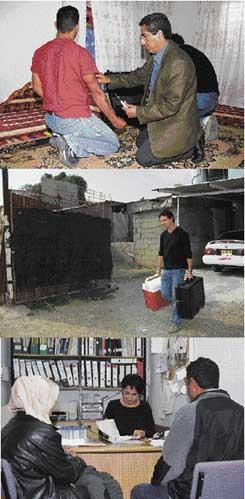

From the top: Dr. Khalil Albador takes a blood sample; Ilan Jungster, Albador's assistant, leads the samples to be cooled; A couple in genetic counseling. Since this is a relatively small and closed community, the chance of a hereditary disease increases. Photographs: Alberto Dankberg

Direct link to this page: https://www.hayadan.org.il/bgudna.html

On a rainy day not long ago, Sana and her husband Nidal entered the concrete building where the Genetics Institute of Soroka Hospital is located. They came to consult about hereditary diseases, and because of society's complex attitude towards these diseases, they asked not to be identified by their real names. "Are you relatives?" The genetic counselor was interested in the beginning of the conversation. No, they both replied. "Not at all? No grandfather, no grandmother? But from the family in general?" They nodded. After that, the counselor inquired if there were any sick children in the family. No, they both replied immediately.

For the past 12 years, the institute has been researching hereditary diseases among the Negev Arabs, and based on the couple's last name, the consultant knew that there were several children in the family with a hereditary disease. The institute, which is equipped with the latest genetic technology in the world, currently offers Bedouins the opportunity to do prenatal tests for a variety of conditions and diseases.

The counselor devoted a lot of time to them, answered their questions and explained to them the advantages, disadvantages and risks involved in genetic testing. She spoke to them in Hebrew, they answered her in short words. "I'll tell you why I call diseases," she continued, "either they are mentally ill, or they die at a very young age, for example. Do you know children who have a problem that they don't feel pain?"

Sana said she knows. "We do a lot of tests today, and also genetic tests," the counselor continued to explain. "We know the problem of insensitivity to pain from the large family to which you belong. What I suggest to do now is a blood test that will reveal if you are carriers of the disease. If only one is carrying, it does not mean that the baby will be sick. If God forbid you are both pregnant, we know there is a risk that the baby will be sick." The institute does such tests, she noted and told them on which days they could come. "Why not", said Sana. "I think it's important to know such things," said the counselor. At the end of the meeting Sana and Nidal were asked if they would indeed come to do the tests. Sana shrugged; "Maybe", said Nidal.

Across the road, in a huge refrigerator at Ben Gurion University, one of the largest DNA repositories in Israel is found in a deep freeze at 70 degrees below zero. It has about 2,000 samples, collected over the years from Bedouin families as part of an extensive project to identify the genes associated with hereditary diseases. The project discovered 16 genes and dozens of mutations linked to diseases and physical phenomena, starting with hereditary syndromes that cause mental retardation or death at a young age and ending with congenital glaucoma and deafness. Patents were registered on two of the genes - one related to obesity and the other to bone density. The project team suggests that the Bedavits use the findings to identify sick babies before they are born, and if they wish, terminate their pregnancy. They are trying to "raise the Bedouin's awareness of the possibility of using genetic tests", as they say. The defined goal of the project, a large part of which is done in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, is to reduce the number of Bedouin babies born with hereditary diseases.

"About 65% of Bedouins marry within the family," says Dr. Ohad Birak, the acting director of the genetic institute in Soroka and head of the genetic laboratory in Ben Gurion. "For this reason, the rate of hereditary diseases among Bedouins is particularly high." There are no more mutations in the genome of the Bedouins than in any other population, but since it is a relatively small and closed community, the chance that two carriers of a gene related to a hereditary disease will marry each other and give birth to a sick baby is greater than in the Jewish population, for example.

"We have been working with the Bedouins since the early nineties," says Prof. Rivka Karmi. "The goal is to reduce infant mortality, which is the highest in Israel, and to improve their well-being." Karmi, who until recently managed the genetic institute in Soroka and is currently serving as the dean of the medical school, started the project and together with her colleagues discovered the first genes associated with diseases in the Bedouins.

"We invested a lot in the relationship with the population," says Birak. "Here there is a real desire and daily activity for help and there is reciprocity - we help them, they help the research and the research helps them back. They are interested in research; The patients and their families are perhaps the main motive in this research."

Birak, like several other genetic counselors at the institute, sees his work as a "Zionist mission". According to him, "among other things, this action is for the benefit of the state. The state wants to see the infant mortality rate decrease and the morbidity rate decrease. This is a grave injustice to the families and great costs to the system."

inside the shantytowns

Dalia Weizman, an epidemiologist from Ben Gurion who works in collaboration with the Institute's team to reduce the number of Bedouin babies born with hereditary diseases, says that "Bedouin women do far fewer tests than women in the Jewish population, mainly because they do not understand what they are testing and what the results mean. There is also opposition to abortions."

According to Hana Beit-Or, a genetic counselor at the institute and one of the main activities in the projects with the Bedouins, a halachic ruling was issued that allows women to terminate their pregnancy up to the 120th day of pregnancy, but this is not always a socially acceptable choice. "Families who have already had a child with a serious illness are interested in research that will find the genetic factors and want to come for tests," says Karmi, "but among the general population there is much less responsiveness."

For many Jewish women, an abnormal genetic finding will lead to a miscarriage. According to sociologists, termination of pregnancy of a baby who does not meet the medical definition of "normal" is often seen in Jewish society as an obvious possibility. For the Bedouins, this is not obvious. According to Beit-Or Weizman, in recent years the rate of Bedouin women choosing to terminate their pregnancy has increased slightly if an abnormal genetic finding is detected in the fetus.

S., who came to the institute because her ultrasound examination revealed that the fetus may have a spine problem, says that if the baby is sick, she will terminate the pregnancy. Wrapped in a headscarf and wearing pants, she says: "I'm the one who will have to raise him later, it's my decision." However, in many cases the husband is a major factor both in the decision to do the genetic tests and in the decision to terminate the pregnancy. He finances the tests, he drives the woman to do them and in many cases he is the one who makes the final decision, says Weizman.

Some of the women claim that the desire to bring them the "good news of genetic testing" and to open up the possibility of abortions to them stems from political-demographic motives: "You want fewer children in the Bedouins," said one of the women after leaving the genetic counseling. "You don't want us to have sick children, so that you can pay us even less than what you spend today." According to Birak and Anat Mishori-Deri, a genetic counselor at the institute, the goal is not for women in Devito to do more tests, "but for more women to be aware of the existence of the tests and the possibility of using them."

The fact that fewer Bedouins than Jewish women access prenatal genetic testing, and the lack of knowledge about the nature of testing in large parts of this population, led the project team to the conclusion that the Bedouins' awareness of the matter should be increased. "We deal a lot with education," says Beit-Or. "We do training courses for teachers and clergy, we prepared a curriculum for XNUMXth graders in genetics and hereditary diseases, we operate genetic counseling services in the community and move from school to school and screen an informational film we made called 'Aisha.' After the screening, we bring up topics for class discussion with the teachers and explain the biology involved."

Teams of genetic counselors go to the shantytowns and encampments in settlements that the state does not recognize exist, conduct workshops and explain the benefits of doing genetic testing. Family physician Dr. Khalil Albador, director of the General Health Insurance Fund clinic in Lekki and professor of medicine at Ben Gurion University, is part of the project team and is responsible for coordinating the meetings with people in the settlements. "I give genetic counseling in the field when I visit them, explain about hereditary diseases and gene carriers and take blood samples. When certain diseases are explained, they accept it very well and are ready for further follow-up and counseling, including tests for pregnant women. It raises their awareness."

The movie "Aisha" encourages Bedouins to do genetic testing and presents the custom of close marriage in a negative light. It seems that the plot of the film has a clear message: Aisha is a young girl who intends to marry one of her cousins. Her sister married, as is customary in the family, a cousin and did not do genetic testing. She had a sick baby. Aisha decides to get tested, and it turns out that she and her cousins carry the same mutation. She goes against the conventions and refuses to marry him. Finally she marries a man from another family and has four healthy children. Her cousin marries another cousin and has a "defective child".

Marriage among close family members does increase the chance of having a sick child, but even so the risk is low. The frequency of the most common hereditary diseases among Negev Arabs ranges from 1 to 1,000 people and 59 to 1,000 for one disease (causing kidney problems). The supporters of the custom of marriage between relatives are presented in the film as old men and people of tradition, who have not yet connected to progress.

Aisha's sister Ben's illness has no name; Her symptoms are also unknown. In the film, the baby's condition is presented as static, he does not develop, he has no personality, he is a child with no features, and the viewer knows nothing about him except for the fact that he is sick with a "very serious disease", and in the end he dies in the garden. The equation, as presented by the doctor in the film, is unequivocal and clear: "If you have an injured child, you will run between doctors, get tired and spend money in vain, because these diseases have no cure."

However, in practice many times proper care and medical treatment can ease the suffering of patients. Also, among the patients there is variety in the type of symptoms, their intensity and the age of their onset; And some of them - such as people with Down syndrome, hereditary deafness and some types of mental retardation - can develop rich lives.

According to Prof. Karmi, the intention was that the actors in the film would be local residents. "But at some point there was a rumbling in the community and it was decided not to participate in the making of the film. In the end, we took actors and Bedouins from Jordan." However, some Bedouin women who conduct health workshops say they use film in their workshops. According to them, norms such as consanguineous marriages and aversion to abortion are so deeply rooted in society that the film helps, through extremes, to open up more possibilities for them.

"I can't tell them not to marry family members, because it won't happen," says Dr. Khalil Albador. "The more important thing is that young couples started to check if they are both pregnant before marriage." Amal A-Sana Al Hajoj, director of Ajik, the Jewish-Arab Center for Equality, Empowerment and Sharing, agrees with him. According to her, "The message should be as Rivka Karmi said in the workshop we held together, 'Don't marry this cousin, but another cousin.'"

About two years ago, the team started such a project among an extended family in which the rate of hereditary deafness is relatively high. The team members came to the village, which is an unfamiliar settlement, and explained to its residents that the incidence of deafness increases as a result of two pregnant people having children together. They offered them to give blood tests and promised that the genetic institute would produce DNA and check if both partners were carriers. If it is found that they are not both carriers, they will be told that they are "genetically compatible and there is no chance that they will have deaf children", and if it turns out that both are carriers, they will be told that they are not genetically compatible. "Pregnancy often carries a stigma, which usually falls on the woman," says Weizman, "this model is less revealing." They started a similar project for thalassemia. According to Weizman and Beit-Or, about 230 samples were collected, but only a few came to receive the results.

Staff members often compare the Deafness Project to "Dor Isharim", a program devised by the ultra-orthodox community in Israel and the United States in which young people are tested before marriage. The matchmaker is given to the families only if the couple is "suitable" or "not suitable". The program almost completely eradicated cystic fibrosis and T-Sachs from the community.

Orli Elmi, coordinator of the health project of the Doctors for Human Rights in the Unknown Villages in the Negev, says that there are indeed similarities between the program run by the genetic team among the Bedouins and "Dor Isharim", but with one essential difference: in "Dor Isharim" the community representatives came to the scientists and doctors , received information from them, decided which diseases they wanted to focus on, how the system would work and which doctors they would work with. On the other hand, the divide-and-rule policy that the state introduced among the Arabs of the Negev undermined the possibility for the development of leadership and representative institutions, and the population as a whole was not asked about its health priorities.

According to Shafra Kish, an anthropologist who studied deafness in Bedouin society in her master's thesis and is currently writing a doctorate in the Netherlands on Bedouin society, it is not self-evident that action should be taken to prevent the birth of deaf children. "There are groups in the world and deaf people, who are very actively raising their voices against this assumption. What is interesting about the families in the Negev with a high rate of deafness is that they do not have separate deaf communities; Many hearing people know sign language. There is recognition that deafness - more than a disability, is mainly a need for another language."

"But", she adds, "relative to the total neglect of the Bedouins, the main problem is not what the geneticist does or doesn't do. In most of the world, the direct results in the field of population health will be much faster if they invest in improving environmental and social conditions, than if they allocate public budgets to identify genes and mutations.

"In the last seven years, there has been no improvement in the level of secondary education, for example. What would happen if only in this area we witnessed a significant change? A deaf person who could read and write could then also do a doctorate in chemistry, and then all the motivation to prevent his birth would also decrease," says Kish.

"If only a small part of the resources were invested in secondary education, if more young women could read and write Arabic, they would be able to read what is written on a medicine box. Educated women have more influence on their lives, then you don't need to send messengers to them to explain what is good for them and what is not. People will have the freedom to make decisions regarding their lives, their health and that of their children; They will be able to determine their own cultural and personal priorities."

as in Ramat Aviv III

In the last decade, the Bedouin infant mortality rate reached 15.3 per 1,000 live births. This is compared to 3.3 among Jewish babies. In 94, a joint program of the Genetics Institute, Ben Gurion University and the Ministry of Health began to reduce the number of babies born in Bedouins suffering from hereditary diseases. In 2002, birth defects were the cause of 36% of all infant mortality cases. According to Dr. Daniela Landau, a specialist in neonatal medicine in Soroka, out of all the babies born with birth defects "about one third can be attributed to hereditary diseases. However, even in other cases we know that hereditary factors are involved, but they have not yet been defined."

Recently, the Ministry of Health allocated about one million shekels for genetic testing in Bedouins for hereditary diseases whose prevalence is at least 1 in 1,000 people. But according to Elmi, "the focus on hereditary diseases exempts the state from a significant discussion of the other problems, which are environmental problems, related to garbage disposal, the lack of electricity, the lack of water, the lack of all infrastructure, the lack of development of services. It also puts the responsibility on the 'primitive' society: the blame in this matter is not on us, but on their culture."

According to Ismail Abu-Saad, professor of education at Ben Gurion and chairman of the steering committee of the University's Center for the Study of Bedouin Society, "With all due respect to my colleagues at the Faculty of Medicine, they come to justify Sharon's plan: it is deceiving the lives of the Bedouins, they are busy blaming the victim. It's very easy to say it's your customs, and your genes and it's hereditary. They come and say that the Bedouins are to blame for the deaths, not the conditions."

"These claims are familiar," says Weizman. "Everyone does what they can in their field. The research on the genetic issue stems from the existence of budgets to engage in this field. But we are interested in doctors, including Bedouins, to write research proposals in each of the health fields. In addition to this, there are children who survive at the age of one, but die before reaching the age of five, and to this are added the costs of treatment and suffering. Those who survive are a great burden on families, society and health services. All in all, this is one of the few areas that can be prevented."

But other areas could also have been prevented if the state had decided to invest the necessary budgets in establishing infrastructures. "Definitely", agrees Weizman, "but it is not within the limited budget of the project, but in a systemic treatment".

In Birak's new research laboratory, all DNA samples, except for exceptional cases, were taken from Bedouins. "This is an optimal population, because it is more in need of diagnosis and also because due to the large number of offspring and close marriages, it is easier than in other populations to reach the diseases," he says as he walks past the research stations in his laboratory, which spans about half a floor. "Obesity, for example. The research of Rivka Karmi and her partners on Bardt-Bidel syndrome in Bedouins led to the identification of a gene involved in obesity, a question that is of great interest to people. If we were to look for it in the general population, it would be almost impossible, because there are a lot of variables."

The laboratory was established, according to him, with donations. "Bradt-Biddle is a disease of mental retardation and very severe obesity, some of them have an extra finger, there is night blindness that develops over time and smaller than normal testicles," says Birk. "The interesting thing is that the disease appears in three different tribes, and in each tribe it results from damage to a different gene, even though its clinical expression is similar."

"These are rare diseases in the general population," he adds, "but because of close marriages, they come to an increased expression in Bedouins. A lot of research has been done on Ashkenazi Jews, so they have many options for genetic testing throughout the country. The research done in the last decade on the Bedouin population in the Negev means that they will have options similar to those of the residents of Ramat Aviv III."

Far from the mouth of the desert

"Thanks to the activity in Soroka, you can start to feel the change. There are all kinds of misconceptions about diseases that are slowly starting to disappear," says A-Sana. "Their work is a step in the right direction." However, she points out that the institute has only one Arabic-speaking counselor, and the consent forms for tests are also written in Hebrew. "The woman signs and actually doesn't always know what she is signing. When the husband is asked to translate, he filters what he wants, and the answers we get from her will also be the man's and not the woman's." The consent forms for participation in studies have been translated into Arabic in recent years, and according to Birak, "almost all participants in the experiment" receive a form in Arabic today and they are now working on translating the forms for the clinical tests.

Birk says he is aware of the importance of language and making tests available. "From time to time Soroka has Arabic courses for the faculty. We are in the process of establishing a clinic for genetic counseling in the Belkia community in collaboration with the district medicine of the general health fund, which will be operated by Dr. Albador. The idea is that the genetic counseling will take place within the community itself. Apart from that, we are in constant contact with Tipat Helav nurses and give them further training from time to time."

The sociologist Arabia Mansor, who works in the Negev in guiding groups for the empowerment of Bedouin women and health development, refers to the question of free choice in the genetic counseling given to Bedouins. "Since the state does not allow a child with special needs to be raised in proper conditions, there is not much freedom of choice. There are no supporting institutions here unless it is to perform the abortion. Maybe the product of the research goes back to the company in a way that will advance it, but it's Pichipax. The investment should not be here, but in the existing, physical infrastructures. Many progressive laws have been enacted by the state, but they do not come close to the entrance of the desert, which thanks to the pretended liberalism is trying to preserve it as a fertile research field for the university, using it as a sociological, anthropological, health and genetic research field. This is the backyard of the State of Israel."

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~579131286~~~48&SiteName=hayadan