Weizmann Institute researchers have discovered bacteria that neutralize a common chemotherapy drug for the treatment of various types of cancer

Cancer patients do not always respond successfully to the treatments given to them. Weizmann Institute scientists recently discovered a new factor that disrupts the response of cancer patients to chemotherapy treatment: bacteria. in a study which Published todayin the scientific journal Science, bacteria living in human pancreatic cancer tumors are described for the first time, and contain an enzyme that neutralizes a common chemotherapy drug used to treat various types of cancer. Using cancer models in mice, the researchers showed how treatment with antibiotics, in addition to chemotherapy, may lead to better results than treatment with chemotherapy alone.

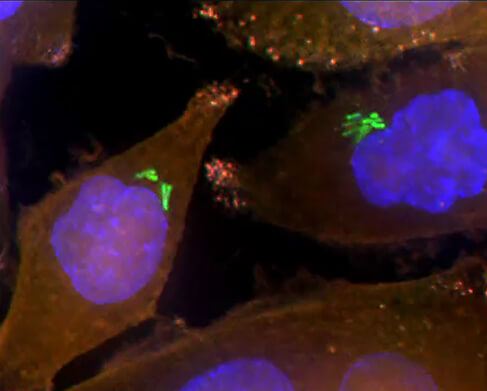

The research was conducted in the laboratory of Dr. Ravid Straussman in the Department of Molecular Biology, led by research student Lior Geller and in collaboration with Dr. Todd Golov and Michal Barzilai-Rokni from the Broad Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology MIT. The group of bacteria found, explains Dr. Straussman, lives inside the tumors and even inside the tumor cells: "Because the subject is so new, we used, first of all, different methods to show that these bacteria do exist in the tumors and are not the result of the contamination of the tumors after they are removed from the body. Then we decided to examine the possible effect of the bacteria on chemotherapy treatment."

The researchers isolated bacteria from the tumors of pancreatic cancer patients and examined how they affect the sensitivity of cancer cells to the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine. And indeed, some of those bacteria prevented the medicine from working. Another study showed that these bacteria digest the active substance of the drug, thereby disabling its medicinal activity. The researchers were able to identify the gene in the bacteria responsible for this - (cytidine deaminase (CDD). They showed that the CDD gene comes in two forms - long and short, and that only bacteria carrying the gene in its long form can disable the activity of gemcitabine; no effect of the drug on the bacteria was observed himself.

The research was born by chance following an incident of bacterial infection in the laboratory: the researchers found a sample that made pancreatic cancer cells resistant to the drug. They located the cause of this in a bacterium that contaminated the cell culture. "We almost threw the project in the trash," says Straussman, "but instead, we decided to check where this accidental find could lead us"

The research group examined more than 100 human pancreatic cancer tumors to show that the same bacteria with long CDD lived inside the patients' pancreatic tumors; They even used different imaging methods to show the bacteria inside the tumors. The large number of tests was necessary, as bacterial infections are a significant problem in laboratory research. In fact, it was an incident of bacterial infection that opened the door for Straussman and his group to the current study. They were looking for evidence that healthy cells in the tumor environment contribute to resistance to chemotherapy. While testing the effect of non-cancerous cells on the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy, they found a sample that made pancreatic cancer cells resistant to gemcitabine. They located the cause of this in a bacterium that contaminated the cell culture. "We almost threw the project in the trash," says Straussman, "but instead, we decided to check where this accidental find could lead us." After the group discovered how these bacteria break down gemcitabine, they began to wonder if other bacteria also have a similar mechanism to disable the drug's activity, and if such bacteria can be found inside human cancerous tumors.

In the current study, follow-up experiments were also done in cancer models in mice with two groups of bacteria: bacteria containing the long form of the CDD gene and bacteria in which the gene was silenced. Only the group whose tumors carried the complete CDD showed resistance to the drug. However, after antibiotic treatment, the mice in this group also responded to the chemotherapy treatment.

Many questions remain open, and Straussman and the research group are currently investigating one of them: whether bacteria can also be found in other types of cancer, and if so, what effects they might have on the cancer and its sensitivity to other drugs, including a new family of drugs that recruit the cells of the immune system to fight cancer.

One response

http://rotter.net/forum/scoops1/431968.shtml?utm_source=rotter.net&utm_medium=newsticker