Are the autoimmune cells in the immune system, which are considered harmful, essential for normal cognitive activity

Marit Selvin, Haaretz, Walla (18/8/04)

Since the 50s, immunologists (researchers of the immune system) have known two basic facts. One: autoimmune cells (cells that are able to attack the body's own components) are harmful to the body; Therefore, during the development of the immune system, a sorting is done in which all cells that recognize self-components are eliminated from the body. The second fact: the cell regiments of the immune system are not supposed to reach the brain, and if they reach it, they will cause damage to various brain functions. The central nervous system (brain and spine) is therefore a neutral area, "out of bounds" for the immune system.

Prof. Michal Schwartz from the Department of Neurobiology at the Weizmann Institute and her research team challenge these two basic assumptions. Schwartz found that immune system cells play a central and important role in the development and maintenance of brain functions. In a study recently published in the journal "Sciences" of the National Academy "Proceedings", Schwartz found with doctoral student Jonathan Kipnis and Dr. Hagit Cohen from Ben Gurion University that immune system cells also participate in the cognitive development of the brain and that without them psychiatric diseases similar to schizophrenia develop in mice.

Autoimmune cells were first discovered in pathological conditions, and therefore the possibility that they play a role in normal physiological conditions was not taken into account. Immunologists have indeed encountered auto-immune cells in the healthy body, but the thought was that these cells "escaped" from the strict control during the development of the immune system and that the body protects itself from them by creating cells that suppress them.

Prof. Schwartz is involved in central nervous system research. Nervous system researchers know that following an injury, large amounts of the neurotransmitter glutamate and free radicals (substances with destructive activity that are created in the cell's metabolism) are created in the brain, and these damage the healthy nerve cells. To prevent the fatal damage to the nerve cells and the spread of the damage, research efforts are focused on finding substances that will neutralize glutamate and free radicals.

Glutamate and free radicals are examples of what Schwartz calls "enemies from within". According to her, these are "substances that in normal physiological states are necessary for functioning, learning, memory, controlling the mental state and survival of nerve cells, such as the neurotransmitters glutamate and dopamine. But when the level of these substances exceeds normal, they become harmful."

How does the body fight "enemies from within" in the nervous system? Science does not have a clear answer to this. "The common perception is that the immune system is designed to protect us only from foreign invaders and not from damage from our own substances," says Schwartz. Is it possible that it is the auto-immune cells, which are part of the immune system, that help in the fight against "enemies from within"?

"It is known that after an injury to the brain or the spinal cord, a spontaneous response to the damage is created, manifested in the proliferation of immune system cells directed against the myelin protein that wraps the nerve fibers," says Schwartz. The conventional approach was that these cells contribute to the severity of the damage because they are directed against self-proteins, but in a series of studies from recent years, Schwartz and her partners showed that these cells are created precisely to help deal with damage caused by internal enemies.

Because autoimmune cells have the potential to be harmful, Schwartz and her team sought to create a controlled autoimmune response that would not cause disease. The search led to the use of Copaxone, a substance used to treat multiple sclerosis. Vaccination with copaxone led to an increase in the desired immune response, which mimics in a controlled manner the activity of the auto-immune cells. In the experiments they conducted, Schwartz and her team found that such an immune response improves the recovery ability of animals that suffered damage to the optic nerve and spinal cord.

"The understanding that auto-immune cells help recovery processes led us to think that actually the primary role of auto-immune cells is that of maintenance, and the help for recovery is actually a by-product of maintenance. In light of this thought, we tried to examine whether the immune system has any role in the cognitive function of the brain."

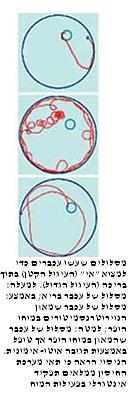

In the new study, the researchers examined the hypothesis that immune system cells play an integral role in brain activity. They exposed mice with defective immune systems to a test in which they had to learn to find an "island" hidden in a pool of water and remember the way to it. Healthy mice learned within a few days to swim to the island by the shortest route and remembered the route for further "journeys". In contrast, mice whose immune systems were impaired took longer to find their way to the island. When the missing immune cells were injected into the mice (which caused a significant restoration of their immune system) their learning ability improved and almost equaled the learning ability of normal mice.

After it became clear that a healthy immune system is necessary for the normal functioning of the brain, the question arose of how, if at all, the immune system affects mental illnesses that are characterized by an imbalance in the activity of neurotransmitters. The scientists hypothesized that in schizophrenia patients, for example, increasing the activity of the immune system may help the brain overcome the defect.

To test this hypothesis, the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain was disturbed in laboratory mice, which led to psychotic behavior that to some extent mimics the behavior of schizophrenic patients. The researchers examined whether, in this case as well, treatment with Copaxone, in order to increase desired immune activity, would allow dealing with the balance of neurotransmitters. In the experiment, it was found that the mice that did not receive Copaxone exhibited behavior typical of schizophrenia patients. In contrast, the mice whose immune system was boosted showed calmer behavior without psychosis-like phenomena.

"It is possible that cognitive damage to the brain that occurs as a result of aging or even exposure to the AIDS virus, originates from an immune deficiency created with age, or as a result of the suppression of the immune system," says Prof. Schwartz. "This insight may lead to the development of revolutionary approaches in dealing with memory loss, behavioral disorders and mental illnesses."