Early identification of children prone to autism may allow for more effective treatment

Parents notice the first signs of autism in their children around the age of 12 to 18 months. They may notice that the child does not make eye contact or does not smile when father or mother enters the room.

But new research suggests you've scanned MRI of the brain makes it possible to find evidence of autism even earlier, long before the child's first birthday. "We are coming to know that there are biological changes [in the brain] that occur when the first symptoms appear or before," she says Geraldine Dawson, a clinical psychologist and autism researcher at Duke University, who did not participate in the new study. "The ability to detect autism in its earliest stages will allow us to intervene and treat children before the syndrome is fully manifested."

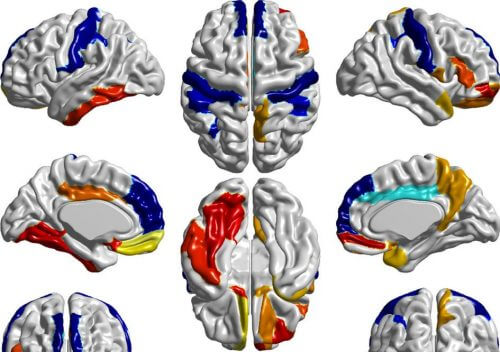

For the purpose of carrying out the research, the results of which Were published In February 2017 in the journal Nature, researchers scanned the brains of 150 children with MRI, three times for each child: at the age of six months, at the age of one and at the age of two. About 100 of these children were at high risk for autism because they had an older brother or sister diagnosed with the syndrome. Faster growth of the surface of their brains was the marker that correctly predicted, in eight out of 10 cases, which of the high-risk children would eventually be diagnosed with autism.

There seems to be a correlation between growth and expansion of the brain and the onset of symptoms, says the paper's lead author, Heather jumped, a psychologist at the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities (CIDD) at the University of North Carolina. However, a study whose sample size is 100 at-risk children is considered too small to be considered conclusive, and there is no need for doctors to rush to send the children for an MRI scan to diagnose autism, says Haslett.

But if the results of the study are confirmed in future studies, they may lead to a new way of screening children at high risk for autism even before their symptoms become obvious. Apparently, this is the time in their lives when treatment will be most effective. The rapid growth pattern of the brain "is a biomarker that might be able to be used to identify the babies who might benefit from early treatment." Dawson says. "This may help these children achieve the best outcomes."

The autistic spectrum, so called because it includes a broad spectrum, or spectrum, of social disorders and challenges in interpersonal communication, is often characterized by compulsive behavior or body movements, among other things. In many cases, parents do not notice behaviors that may indicate autism until about 18 months of age, an age when normal children are usually expected to speak and respond socially. If we show parents the neurobiological changes occurring in their children before the behavior changes, the research may help them better understand the experiences their children are going through, says the biopsychologist Alicia Halliday, the chief scientist bAutism Science Foundation, an association that supports scientific research but did not support the new research.

And if they show scientists how the brain develops before the child is diagnosed with autism, the study may give them new insights into the genetic factors that trigger autism, says James McPartland, a psychologist at the Yale University Child Research Center, who was also not involved in the study. "When there is more information about neural pathways, we can infer more about genetic pathways," he says.

What the study failed to show was a possible difference between autism in families with more than one child with the syndrome, and autism that apparently has no family connection. One in 68 children is diagnosed with autism, but among younger siblings of children on the spectrum, the diagnosis rate reaches one in five.

Some research now being conducted focuses on these younger brothers and sisters of children with autism, who are more likely to develop autism as well. This group is easier to study than the general public because fewer subjects are needed to find children who will eventually develop autism. But it is not yet clear whether these young brothers differ in any sharp and obvious way from other children on the spectrum.

To find a large enough number of children to make the study useful, the researchers followed more than 500 babies, scanning some of them in the middle of the night, while they were fast asleep. It took years to collect enough valid data on 150 of them, and the families agreed to donate their time. "We often underestimate the amount of work required to do this kind of research," says Dawson.

Hazelt, and a colleague at CIDD, Joseph Piven, also one of the main authors of the article, say that they started the research about ten years ago. This came after earlier research suggested that the brains of children with autism are already abnormally large by the time the children reach their second birthday, and before the behavioral symptoms of autism usually appear.

Pivan, a psychiatrist by training, says that the mechanism is not entirely clear. But he hypothesizes that babies who will develop autism experience the world differently in their first year of life than babies who will not develop autism, and that this different experience of the world may contribute to changes in brain development in children with autism that will occur later.

Dawson claims that because the brain undergoes so many changes in the first year of life, this may be a critical window of opportunity in development, where behavioral therapy, such as teaching the baby to pay attention to the parents' facial expressions, may have the greatest impact. And since until recently it was not clear that the differences in the brain that characterize autism begin so early, during infancy or even during pregnancy, there are currently no treatments designed for such tender babies. Such treatments are currently being tested. The new research may give researchers a possible tool to diagnose babies, Dawson says, and thus allow new ways to test these new treatments.

McPartland calls the possible treatments "hyper-parenting". While there is no difficulty in leaving a normally developing baby to play with a toy alone, he says, a child prone to autism may benefit from more communication with a father who makes sounds or a mother who laughs and sings. "Make sure as much as you can that a child is kept in an environment saturated with social information," he says. "And hope the baby picks up on it."

About the writer

Weintraub Foundation - Freelance reporter on health and science who regularly writes for the New York Times, STAT, USA Today and more.

More of the topic in Hayadan: