Research done with the help of current mathematical models and historical documents points to community health programs and the implementation of social distancing as the most likely explanations for the surprising and mysterious collapse of the typhus epidemic in the Warsaw Ghetto

From: Australian University of Technology Translation: Ziv Adaki

In the face of unprecedented overcrowding, hunger and many living on the streets - the outbreak of an infectious disease should be almost unstoppable, but during World War II, Jewish doctors in the Warsaw ghetto stopped it. Children living on the street in the Warsaw Ghetto, 1941, NIEZNANY/UNKNOWN/PUBLIC DOMAIN

Research done with the help of current mathematical models and historical documents points to community health programs and the implementation of social distancing as the most likely explanations for the surprising and mysterious collapse of the typhoid epidemic in the Warsaw ghetto, described by the survivors at the time of the conference.

In the midst of the Corona epidemic, historians and epidemiologists seek to learn from past outbreaks of infectious diseases and found such an almost defiant outbreak in the Warsaw Ghetto, in Nazi-occupied Poland, during World War II. While dealing with extreme overcrowding, hunger and appalling sanitary conditions, the Jews trapped in the ghetto managed to control the spread of typhoid and saved about 100,000 people. A new study, showing how they managed to do this, is a mirror image of the efforts of the world today, under conditions that should be infinitely simple.

After conquering Poland, the Nazis imprisoned more than 450,000 Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto, in an area of approximately 3.4 square kilometers. For the sake of comparison, in Manhattan as a whole, a quarter of the population lives in an area 17 times larger. Even in the most crowded refugee camps today, there is more human space.

"The Warsaw ghetto was a perfect breeding ground for the typhoid bacteria to spread, and it did spread through the Jewish population like wildfire," said Prof. Levi Stone from RMIT University in his statement.

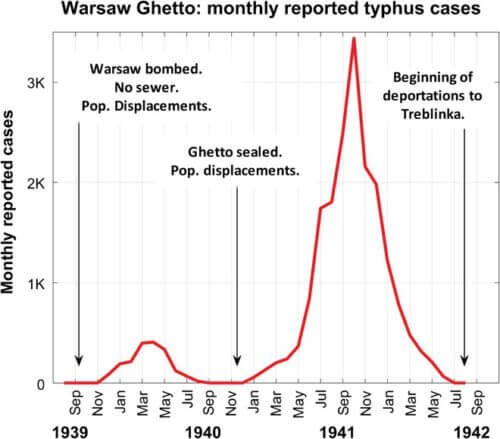

Indeed, about 30,000 ghetto residents died of typhus, but three times as many survived. Furthermore, the plague was stopped long before it infected the majority of the population. And no less than amazing, the infection rate dropped precisely when it was expected to jump, in view of the harsh winter of 1941-1942.

"Many thought it was a miracle," says Stone, who teamed up with scientists from around the world to study the spread of typhoid. In the journal Science Advances, he showed how science, and especially the mobilization of the Jewish doctors, brought about the stopping of the plague. Although the disease we face today is different from typhoid, the typhoid outbreak was defeated using epidemiological methods similar to those that epidemiologists promote today: sanitation programs, self-isolation and physical distancing.

And a crucial aspect, those imprisoned in the ghetto listened to the doctors' recommendations.

Stone was able to reach these conclusions thanks to the insistence of the ghetto doctors to document what was happening. These records are the most substantial source of information we have about the effects of famine, but the information they contain about the typhoid epidemic has not yet been investigated using modern epidemiological and statistical methods.

"I spent hours and hours in libraries all over the world looking for rare documents or publications where I could find details about the interventions that were implemented and the rates of the plague itself," says Stone. He found evidence of hundreds of lectures given by doctors to the public in the ghetto about the importance of personal hygiene, self-isolation when sick and physical distancing to stop the spread of typhus, as well as an underground medical university that trained medical students in infection control.

The type also ran rampant in cities in Ukraine, where Jews were also imprisoned, and in one of them, Sherrod, it was stopped as soon as soap production began and cleaning services were implemented, which supports Stone's claim.

Stone and his co-authors of the article point out that the Nazis used typhoid, which threatens the health of Germans, as justification for gathering the Jews in the ghetto, and then also for sending them to the extermination camps. "This is an example of humanity's ability to turn against itself, based on race-based epidemiological principles, just because of the appearance of a bacterium," they write. In the face of an epidemic that disproportionately causes the death of ethnic minorities, we cannot assume that such atrocities are a thing of the past.

The historical analysis highlights the critical importance of collaboration and active mobilization of communities in efforts to defeat pandemics and epidemics like COVID-19, rather than relying too heavily on government regulation.