The hottest spot on a planet near a distant star isn't where astrophysicists expect it to be—a discovery that challenges scientists' understanding of the many such planets in solar systems outside our own.

The hottest spot on a planet near a distant star isn't where astrophysicists expect it to be—a discovery that challenges scientists' understanding of the many such planets in solar systems outside our own.

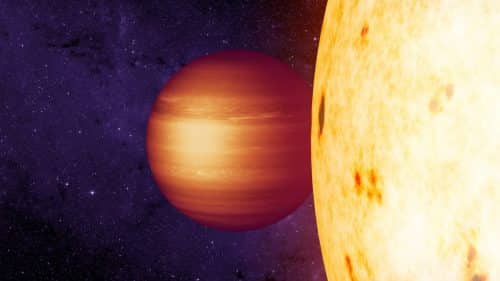

Unlike our familiar planet Jupiter, the so-called "hot Jupiter" planets orbit surprisingly close to their host star - so close that it usually takes them less than three days to complete orbit. One hemisphere of such a planet constantly faces its host star while the other constantly faces the dark side.

Not surprisingly, the "day" side of the planet gets much hotter than the night side, and the hottest point of all tends to be the point closest to the star. The theories and observations of astrophysicists indicate that these planets also have strong winds blowing eastward near their equator, which can sometimes move the hot spot eastward.

In the mysterious case of the extrasolar planet CoRoT-2b, however, the hotspot turns out to be in the opposite direction: west of the center. A team of researchers led by astronomers at McGill University's McGill Space Institute (MSI) and the Institute for Research on Extrasolar Planets (iREx) in Montreal made the discovery using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. Their findings were reported on January 22 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Wind in the wrong direction

"We previously studied nine other cases of "hot Jupiters", giant planets that orbit super close to their stars. In all cases, they had winds blowing eastward, as the theory predicts," says McGill astronomer Nicholas Cowan, a co-author of the study and a researcher at MSI and iREx. "But now nature surprised us. On this planet, the wind is blowing in the wrong direction. Since the exceptions are often the ones that prove the rule, we hope that the study of this planet will help us understand what activates "hot justice".

CoRoT-2b, discovered a decade ago by a French-led space observatory mission, is located 930 light-years from Earth. Many other "hot Jupiter" planets have been discovered in recent years, but CoRoT-2b has continued to interest astronomers for two reasons: its large size and the questionable spectrum of light emissions from its surface.

"These two factors indicate that something unusual is going on in the atmosphere of this 'hot Jupiter,'" says Lisa Dang, a doctoral student at McGill and lead author of the new study. By using the Spitzer Infrared Array camera to watch the planet as it completed an orbit around its host star, the researchers were able to map the brightness of its surface for the first time, and discovered the westward hotspot.

New questions

The researchers offer three possible explanations for the unexpected discovery - each of which raises new questions:

- It is possible that the planet rotates so slowly that one revolution takes longer than the complete revolution of its star; This could create winds that blow west instead of east—but it would also challenge theories about the gravitational planet-star interaction in such tight orbits.

- There may be an interaction between the planet's atmosphere and magnetic field that changes its wind pattern; This could be a rare opportunity to study the magnetic field of an extrasolar planet.

- Large clouds covering the eastern side of the planet could make it appear darker than it would without the clouds—but this would undermine existing models of atmospheric circulation on such planets.

"We will need better data to shed light on the questions raised by our findings," says Dang. "Fortunately, the James Webb Space Telescope, whose launch is planned for next year, will be able to deal with this problem. Armed with a mirror with a collection power XNUMX times higher than Spitzer, it will provide us with superior data than ever before."

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/01/180122110942.htm

One response

They will rise and succeed, now with the artificial intelligence they may be able to pass the barrier "16000 times" than the existing one or then a lot of light will be shed.