Designing figures of heroes as giants in Gothic art marked the strengthening of urban power, the weakening of religion and the beginning of social mobility

Medieval art in Europe, from the end of the Roman Empire to the beginning of the Renaissance, is divided into several periods; One of them is Gothic art - a style that was common for about 350 years and especially at the height of the Middle Ages (from the middle of the 12th century to the end of the 15th century). This style included architectural, pictorial and sculptural elements, and was based on philosophical-religious and courtly concepts.

Prof. Assaf Pincus, expert in medieval art history, senior lecturer in the art history department at Tel Aviv University and honorary professor at the University of Vienna, studies culture and history through art. It focuses on Gothic sculpture and painting that existed in German-speaking areas of Europe during the Middle Ages (mainly between the 13th and 15th centuries).What is the question? Why were huge statues built in city squares in Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries? And why does their identity not match the signs that appear on them?

At the beginning of his career he was involved in the world of religious art and tried to understand the place of the imagination in it. He says that he discovered a whole array of statues in medieval Europe that lacked identifying marks (such a mark is, for example, a black lily for the Holy Mary and represents virginity and purity). After researching the subject he discovered that these statues were stripped and dressed periodically, depending on the holiday being celebrated. According to him, "When the sculptures were stripped, the viewer could cast identities on them according to his imagination. This discovery made me delve into the world of medieval imagination, which also exists in religious art. I was interested in exploring a 'secular' experience in a religious world."

Later, Prof. Pincus decided to investigate the concept of violence in its modern and legal sense based on paintings and sculptures of torture of saints created in churches in Germany in the 14th century. They expressed a variety of executions, such as an ax blow to the head, pulling out nails, gouging out eyes and cooking in oil. According to him, "Violence has always been expressed in art, but as an allegory and not as a representation of cruelty. The paintings and sculptures of martyr torture expressed a change in this regard and I asked myself what led to this. In a philosophical-sociological study I conducted I discovered that in the 14th century man was defined, for the first time, as the owner of his body. Until then this ownership belonged to the church. Therefore, at this stage the question was asked if it is permissible to hurt a private body. This is how the concept of violence began to be represented in art in its modern-criminal sense, and art began to participate more in a discourse that is also legal and ethical and not just religious."

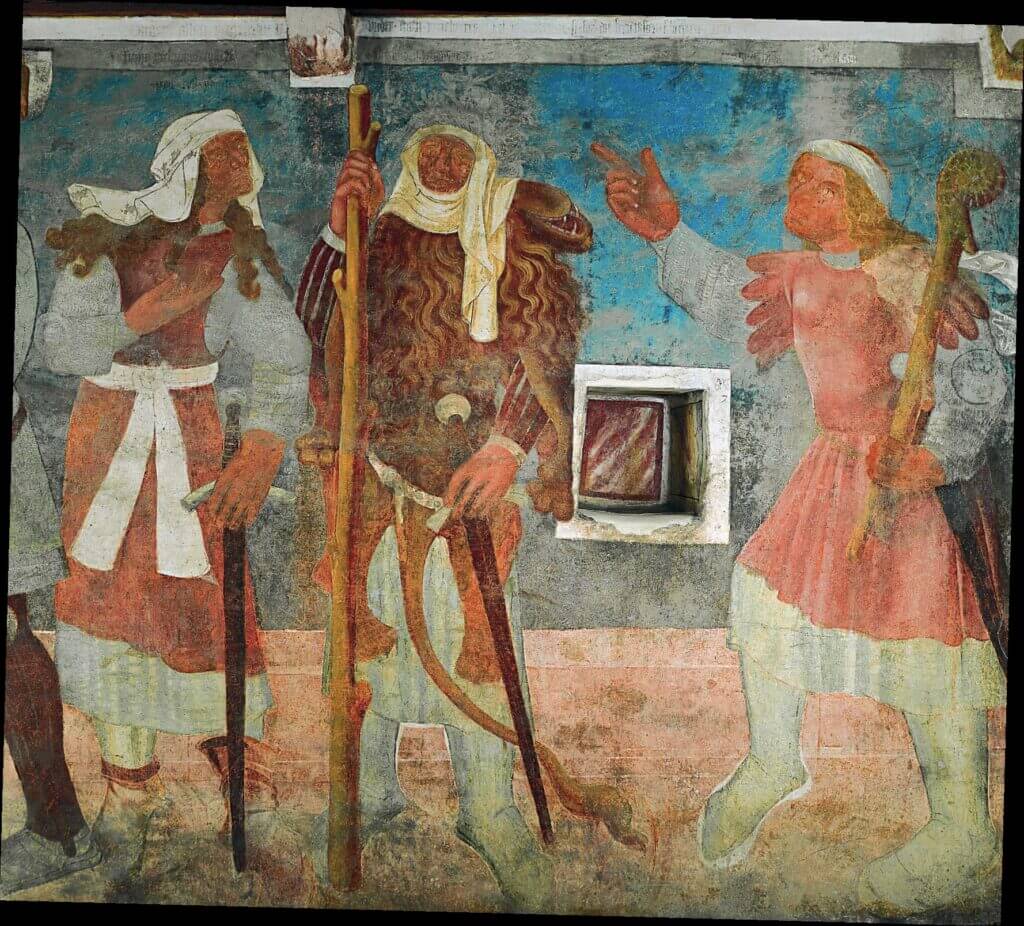

In the 14th and 15th centuries, statues of heroes and heroines designed as giants began to appear in city squares in Europe, in countries such as Germany, Russia and Croatia, about ten meters in size. Their symbols were replaced by symbols that feature giants from Norse and Germanic mythology

In Prof. Pincus's current research, which is supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation, and which is called "Giants in the City" and is now in its third year, he discovered that in the 14th and 15th centuries, in European cities, in countries such as Germany, Russia and Croatia, statues the size of About ten meters, of heroes and heroines designed as giants and giantesses. Their symbols were replaced by symbols that feature giants from Norse and Germanic mythology. Thus, for example, the statue of Roland from the city of Bremen in Germany, the nephew of Charlemagne (one of the greatest rulers of Europe in the Middle Ages), who fell in the battle against the Muslims in Spain (Battle of Ronsbo, 778); His permanent symbols, such as a helmet and a horn with which he warned Karl of a military ambush, were replaced by legendary symbols - such as a hovering shield, a giant's power belt, and dwarves and tiny animals at his feet. Prof. Pincus wanted to investigate why these heroes were sculpted as giants, and why their identity does not match the signs on them, especially in view of the fact that they were placed in such a central place in the city. According to him, "In the 14th and 15th centuries, the world was Christian. If so, why did they begin to give the heroes the identity of giants originating from pagan culture? In addition, in the Bible and in mythologies, giants are a symbol of sin, excess of power, sexuality and pride (for example, the flood that God sent to wipe out giants from the face of the earth, Goliath, and the giants that were defeated in England by Brutus of Troy). Why, then, were heroes designed as giants?".

To get answers to these questions, Prof. Pincus scanned documentation that appears on 30 giant statues, in the libraries and archives of churches and cities in Europe, which include details about the circumstances of their construction and destruction. He discovered that in these centuries, the urban-civil power grew stronger, while the religious power weakened. The cities that were freed from the rule of the church looked for new symbols of identity and adopted the giants as a symbol of independence. Since the giants were creatures "in between", between a wild and civilized world, between a monster and a human, between the despicable and the sublime, they began to symbolize states of transition and social mobility (the ability to change from a low-class person to a high-class person); Their symbol changed from threat to strength. This is how heroes were designed as mythological, legendary, superhuman giants. The contracts for their construction were drawn up by the city councils or castle owners (mainly those who climbed the social ladder, from the status of merchants to the status of low nobility). Says Prof. Pincus: "This is actually how a new symbol for urbanism, independence and politics was created. I discovered that this phenomenon existed in other cultures (eg giant statues in China). Following this research, I started writing the book 'Global History of Giants'".

Life itself:

Prof. Assaf Pincus, 52, married plus two (23, 20), from Herzliya. These days he teaches art history at the International University of Venice. In the past he studied pastry making in Austria and practiced it for ten years. Later he made a U-turn and began to study art history ("I always loved art, I researched the field back in my guard duty as a gunner, but I didn't think I could make a living from it"). Today in his spare time he bakes, writes novellas and dances.