An analysis of charcoal remains collected as part of an excavation at the Tel Tsaf polyglot site in the Jordan Valley determines that these are the remains of olive trees. Since the Jordan Valley is outside the olive's natural habitat, this means that the local residents planted the tree on purpose about 7,000 years ago

A new study by the Tel Aviv and Hebrew universities reveals for the first time the earliest evidence in the world of the culture of fruit trees. According to the researchers, an analysis of charcoal remains collected as part of an excavation at the Tel Tsaf polyglot site in the Jordan Valley determines that these are the remains of olive trees. Since the Jordan Valley is outside the olive's natural habitat, this means that the local residents planted the tree on purpose about 7,000 years ago.

"In the field of archaeological botany, this is unequivocal proof of the civilization of a tree, so that we have before us the earliest evidence in the world of the domestication of the olive"

"Wood was the plastic of the ancient world"

The groundbreaking research was conducted under the leadership of Dr. Dafna Langut From the Department of Archeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures named after Yaakov M. an alcove and the Steinhardt Museum of Nature at Tel Aviv University. The charcoal remains were found as part of the excavation by Prof. Yosef Garfinkel from the Institute of Archeology at the Hebrew University. The results of the surprising and groundbreaking research were published in the prestigious journal Scientific Reports from Nature.

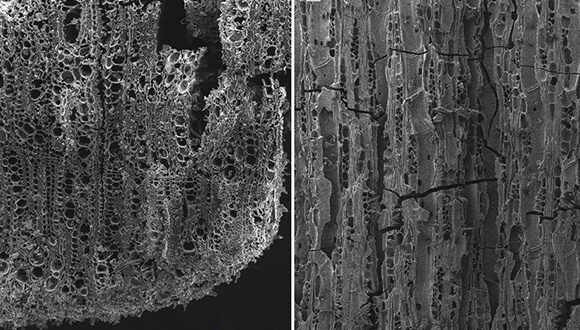

"The laboratory for archaeobotany and the study of the ancient environment, which I head, specializes in the microscopic identification of plant remains. In the case of trees, even when they are carbonized, they can be identified based on their anatomical structure and thus know which species they are," says Dr. Langut. "Wood was the plastic of the ancient world. They were used for construction, to create tools and furniture as well as a source of energy. Therefore, identifying remains of trees from archaeological sites, for example charcoal from bonfires, allows us to reconstruct the trees that grew in the natural environment of the sites and to understand when man began to grow fruit trees."

In the laboratory, Dr. Langot recognized that the coals belonged to olive and fig trees. "Olive trees are from the wild flora of the Land of Israel," says Dr. Langut, "but they do not grow in the Jordan Valley. Someone brought them there on purpose, meaning transferred the knowledge, and the seedling itself, outside the tree's natural habitat. In the field of archaeological botany, this is unequivocal proof of the civilization of a tree, so that we have before us the earliest evidence in the world of the domestication of the olive."

"In addition, I also identified many remains of young fig branches. The fig does grow wild in the Jordan Valley, but there is no reason for people to bring many branches to the site. They are worthless as raw material for making furniture or as fuel. Therefore, I hypothesize that the origin of the fig branches is pruning waste, a practice that is still accepted today in order to increase the yield of the fruit trees", she adds.

"At the Tel Tsef site, we find the first evidence in the world of cultivated fruit trees and alongside them stamps, also among the earliest, which testify to the beginning of administrative processes. All the findings point to the wealth of the residents and the first steps towards their transformation into a complex and stratified society, with the status not only of farmers but also of officials and merchants"

The first olive and fig groves in the world

The remains of the trees examined by Dr. Langot were collected by Prof. Yosef Garfinkel from the Hebrew University, who directed the excavation at Tel Tsef. "Tel Tsef is a large prehistoric village, which existed between 7,200 and 6,700 BC, in the Middle Jordan Valley south of Beit Shean. Large courtyard houses were discovered there, and in each of them a number of silos for keeping the crops. The storage capacity is up to 20 times greater than the caloric consumption of a family, so it is clear that this is a large accumulation of wealth. This is reflected in the production of magnificent pottery, painted at the highest level. In addition, special objects were found that were brought from far away: pottery of the Ubaid culture from Mesopotamia, obsidian from Anatolia, a copper awl from the Caucasus and more," explains Prof. Garfinkel.

The excavation at the Tel Tsef polytheistic site in the Jordan Valley

Dr. Langot and Prof. Garfinkel were not surprised that the residents of Tel Tsef were the first in the world to intentionally grow olive and fig groves, since growing fruit trees indicates luxury, and the site at Tel Tsef was known to be particularly rich.

"Domestication of fruit trees is a process that takes many years and is therefore suitable for a seven company and not for a company that is struggling to survive. The trees bear fruit for the first time only 4-3 years after they are planted. Since fruit tree orchards require a lot of initial investment and are life-extending, this also has deep economic and social implications in the context of land ownership and inheritance for future generations. These are moves that point to the beginning of the formation of a complex society," says Dr. Langot and adds that "it is possible that the residents of Tel Tsef even traded in the products they produced from the fruit trees: olive oil, edible olives, and olive oil. These are characterized by a long shelf life and without a doubt enabled a long-term trade that led to the accumulation of material wealth, and may have led to taxation. These are the first steps to transform the residents of Tel Tsef into a society with a social-economic hierarchy and a supportive administrative system."

"At the Tel Tsef site, we find the first evidence in the world of cultivated fruit trees and alongside them stamps, also among the earliest, which testify to the beginning of administrative processes. All the findings point to the wealth of the residents and the first steps towards their transformation into a complex and stratified society, with the status not only of farmers but also of officials and merchants", concludes Dr. Langot.

- Rare evidence of the use of fire more than 800 years ago was uncovered at an archaeological site in the Galilee

- Tel Aviv University researchers: Middle Eastern empires collapsed because of a climate crisis

- The hygiene patterns of the wealthy of Jerusalem during the days of the First Temple

- Dramatic climate changes at the end of the Ice Age enabled the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to farmers