A defense mechanism discovered in bacteria may make it possible to improve the resistance of agricultural crops to pests

Brown spots popping up on the leaves of a favorite pot? This is evidence of the strenuous action of its immune system: in response to various pests, be they bacteria, virus or fungus, a defense mechanism is activated in the plant which destroys infected cells, and some other cells in their environment, in order to prevent the infection from spreading to the entire plant. in research the published in the scientific journal Nature Weizmann Institute of Science scientists reveal the evolutionary origins of this mechanism: a defense system of bacteria against viruses. Their findings may shed new light on the operation of defense mechanisms in plants and make it possible to strengthen their resistance to lesions that annually cause crop losses worth billions of dollars.

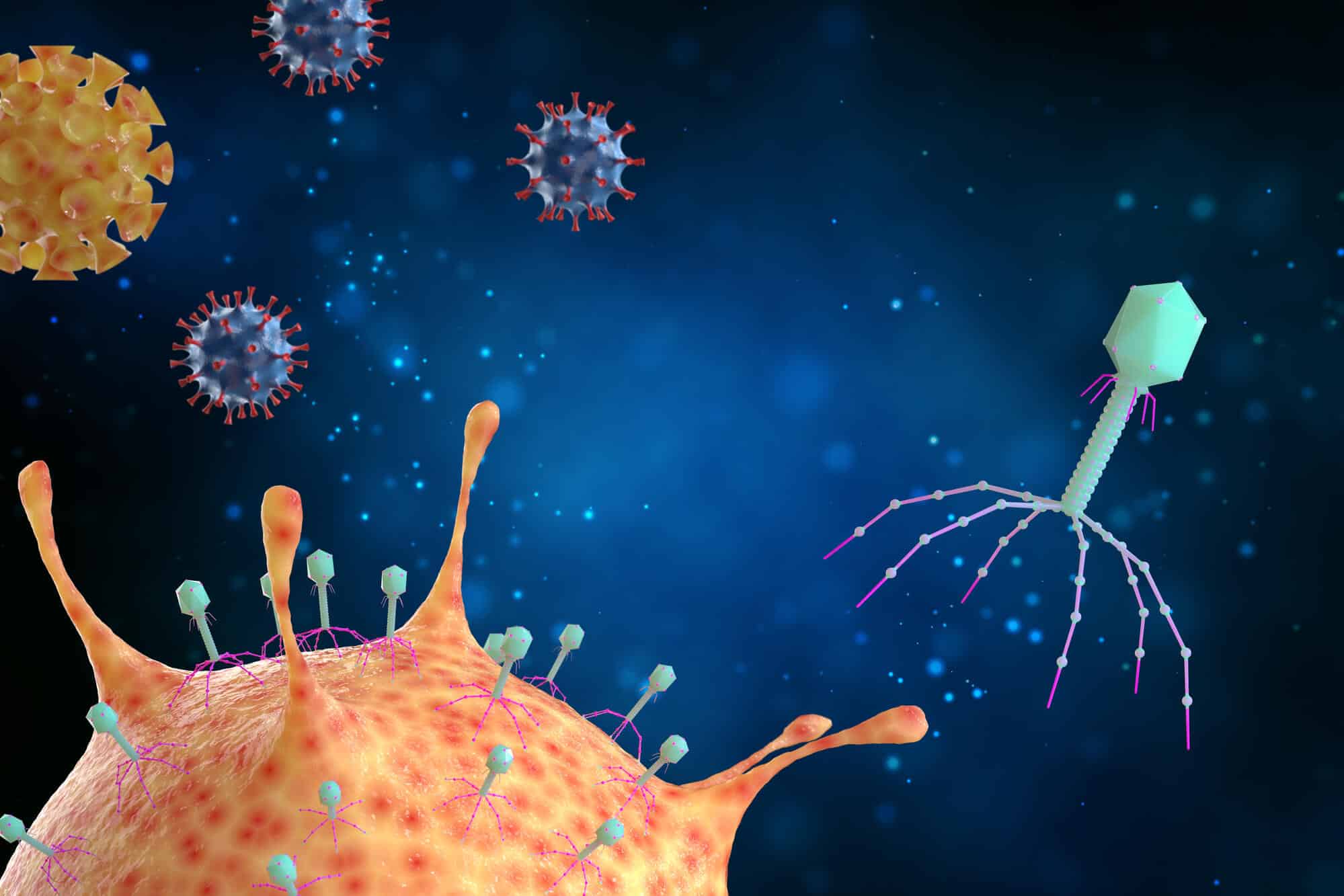

Since the dawn of evolution, bacteria have been waging a continuous campaign against viruses called phages, which look like miniature versions of lunar rovers. The phage inserts its genome into the bacterial cell and causes it to produce more and more copies of itself until the cell explodes and dies - and the infection spreads to the rest of the colony. the laboratory of Prof. Rotem whistles In the department of molecular genetics at the institute, he specializes in researching the defense systems of bacteria. In a new study led by the research student at the time, Dr. Gal Ophir, they discovered in his laboratory that a protein containing a segment called TIR plays an important role in the bacteria's fight against phages. Surprisingly, scientists in the United States and Australia discovered about two years ago that a similar protein with a TIR segment is present in plants that defend against pests, but this mechanism has not been deciphered.

As part of the new research, Ofir and his partners revealed the mechanism of action of the protein in bacteria, and later showed that its action in bacteria is similar to its action in plants. First, the researchers mapped the chain of molecular reactions that the protein activates in the bacterium: when a phage penetrates the bacterial cell, the protein senses the invasion and produces a molecular signal that leads to the activation of another protein, which in turn destroys a molecule essential to the bacterium's metabolism. In its absence, the bacterium deprives itself of its life before the phage's reproductive program gains momentum, and the infection is blocked.

The big surprise was recorded when the researchers transmitted the molecular signal that produces the protein from plants to bacteria - the message got through and the suicide plan was launched. Although the TIR mechanism in plants still requires careful mapping, the research shows that the mechanism is quite similar to that discovered in bacteria: in both cases, a protein with a TIR segment recognizes the invader and produces a chain reaction that leads to the suicide of the cell - the bacterium or one of the plant cells.

"Our findings establish a direct evolutionary link between the immune systems of plants and bacteria," says Prof. Sorek. "Furthermore, our study forms a basis for future studies that will examine how this central defense system works in plants." These studies may lead to new ways to strengthen the immune system of plants to make them more resistant to lesions - a burning issue considering the extent of the loss of agricultural produce every year and the lack of effective solutions. For example, these days a bacterial infection threatens to wipe out citrus groves around the world: in Florida, the citrus crop was recently cut in half, and so far no answer to the disease has been found. New insights into the defense mechanisms of plants will perhaps help in the future to better protect the orchards and other plantations.

Dr. Ehud Herbst, Maya Brauz, Daniel Cohen, Adi Milman, Dr. Shani Doron, Nitzan Tal and Dr. Gil Ameti from the Department of Molecular Genetics of the Institute participated in the study; Daniel Malhiro from MS-Omics, Denmark; and Dr. Sergey Malitsky from the Department of Life Sciences Research Infrastructures of the Institute.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- A mechanism has been revealed by which "good" viruses eliminate "bad" bacteria and stop their culture

- Antivirals discovered in bacteria may be used as drugs for viral diseases

- What are viruses, how do they spread and how do they attack us

- dislodge the resistance

- How do the bacteria distinguish 'between enemy and lover'?